Scientist of the Day - Richard Oldham

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

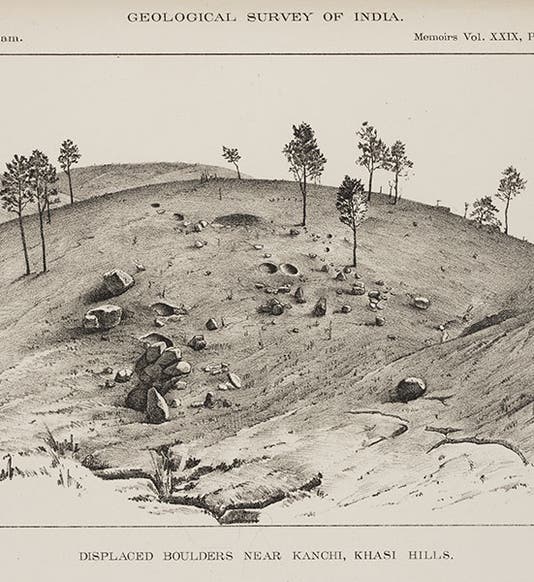

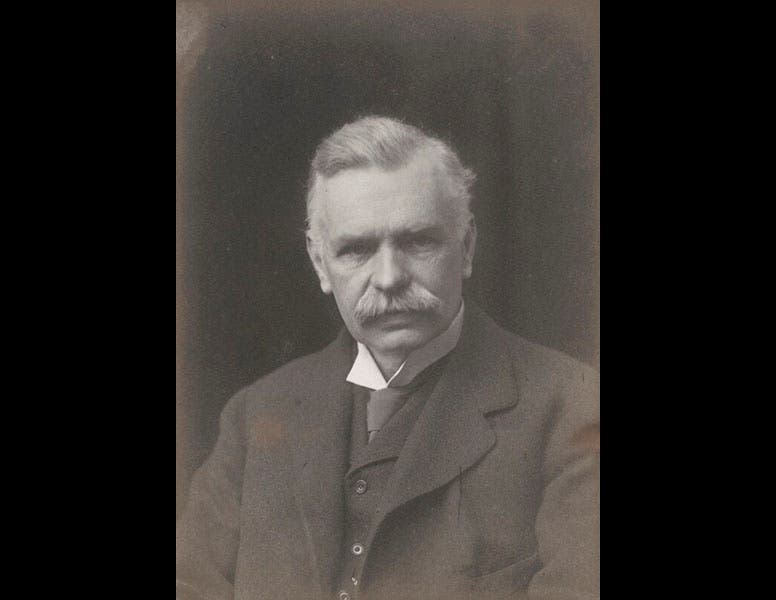

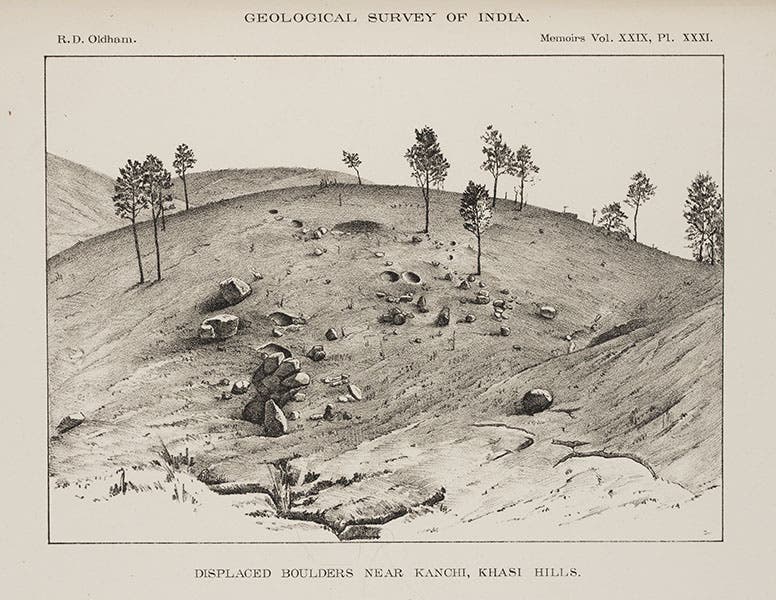

Richard Dixon Oldham, an Irish geologist, was born July 31, 1858. Oldham spent much of his career in India, working for the Geological Survey of India. In 1897, eastern India was wracked by a massive earthquake, referred to today as the Assam earthquake, and in 1899, Oldham published a comprehensive study of the event in the Survey’s Memoirs. Two of the photos above are from this volume; one shows a displaced railroad track, and the other reveals holes in the grounds where boulders were shot straight up from the force of the upheaval (first two images). In Assam, the Shillong Plateau moved vertically almost 50 feet, one of the largest displacements ever recorded. But Oldam's study did not just reveal the extent of the damage; he also had a lot to say about the nature of seismic waves. Seismology as a science was about 40 years old, but no one yet understood much about seismic waves, or that there were different kind of waves. In this work, and in a separate study of 1900, Oldham showed that there were three kinds of seismic waves; those caused by compression of the rock, which he called "condensational" waves (we now call them pressure waves or p-waves), those that are essentially lateral vibrations of the rock, which he called "elastic" (we now call them shear waves or s-waves), and surface waves. He revealed that they travel at different speeds, and that that one can use their travel time to calculate the density of the rock they pass through. As it would turn out, you can use them for other things as well.

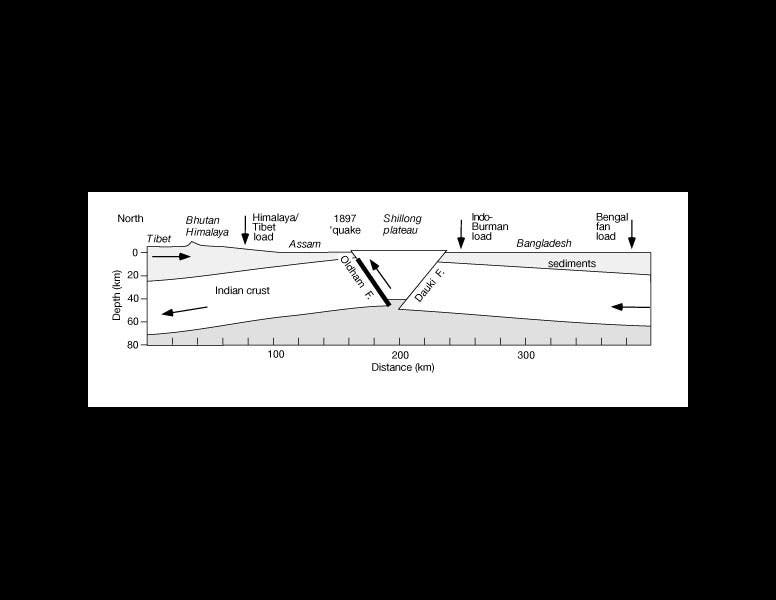

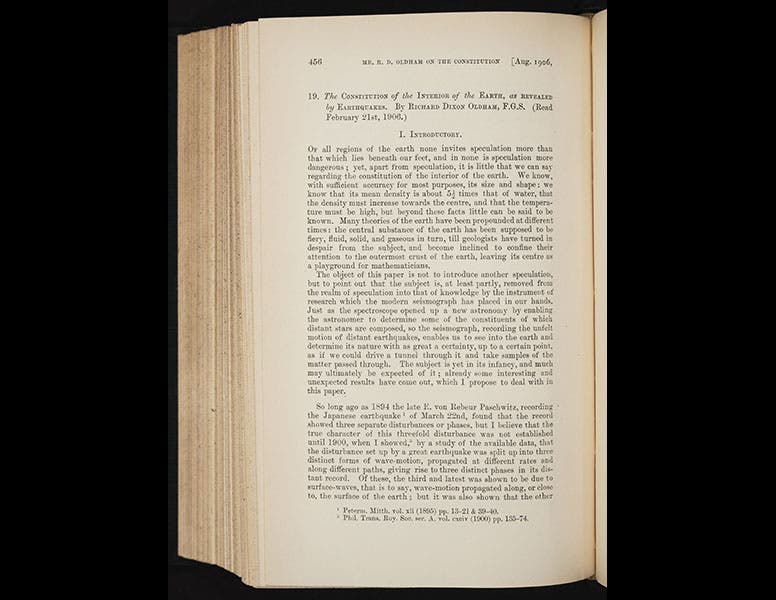

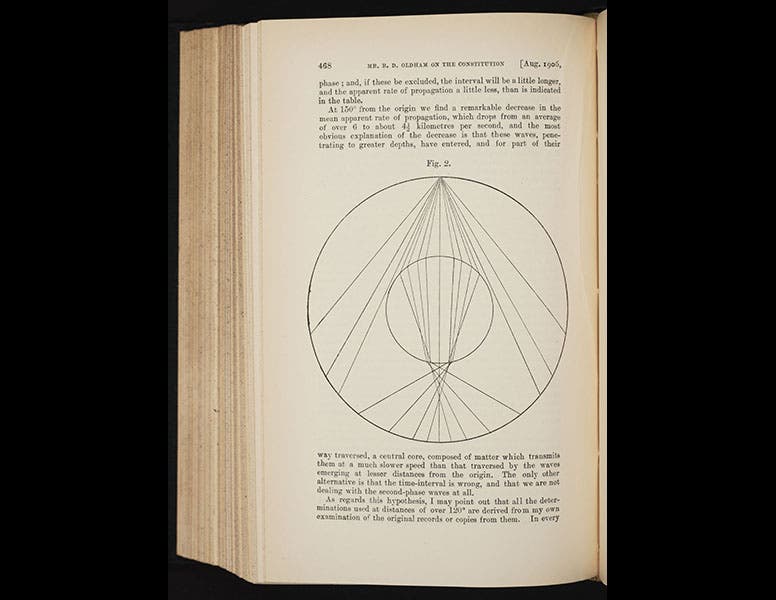

In 1906, Oldham demonstrated that we can use seismic waves to reveal the internal structure of the earth. In a paper published in the Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London (third image), he showed that p-waves (using the modern term) terminate about 120 degrees away from the epicenter of a seismic event, and then pick up again further on, suggesting that they are being refracted by a denser kind of rock that lies far below the surface. The s-waves terminate as well, and then they either show up again greatly altered, or they don't show up at all (Oldham wasn't sure which was the case). From this information, Oldham concluded that the earth has a large core - he estimated its radius to be about 40% the radius of the earth - and he even included a diagram that shows the core and the wave-paths that reveal it (fourth image). It is the first diagram ever of the earth's core. Later geologists would realize that the s-waves really do disappear, indicating that at least part of the core is liquid. In 1909, the Croatian geologist Andrija Mohorovičić would discover the boundary between crust and mantle, and a solid inner core would be inferred in 1936 by Danish seismologist Inge Lehmann, all using the seismological principles developed by Oldham.

Recent studies of the 1897 Assam earthquake indicate that the Shillong Plateau moved upward along two blind faults. One of these faults has been named the Oldham fault (sixth image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.