Scientist of the Day - Robert Bakewell

Robert Bakewell, an English geologist, died Aug. 15, 1843, at the age of about 76. Bakewell was somewhat of a geological oddity, in that he did not have an academic position and was not a member of the Geological Society of London, or any other scientific society. He seems to have supported himself by giving geological lectures all across England. And yet he was the author of the most popular geology textbook in all of England between 1813 and 1840 or so. His Introduction to Geology was first published in 1813, quickly followed by a second edition in 1815, and then a third (1828), a fourth (1833), and a fifth (1838). Each of these was revised and enlarged from the one before.

We happen to have all five English editions plus two American editions in our collections. Since we don’t know very much about Bakewell the person, I thought it might be interesting, with Bakewell as our focus, to ask: what guides authors when they write new editions of popular books, and why do Libraries bother to collect all these later editions? Why isn't a first edition enough?

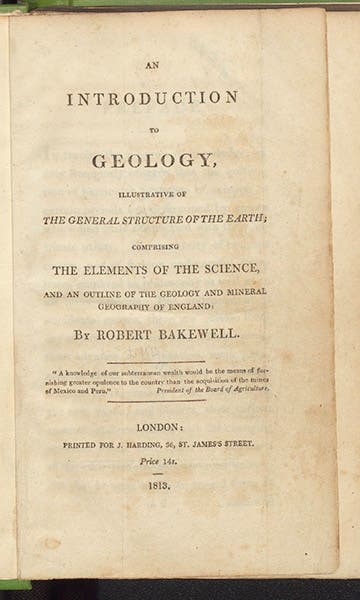

To this end, I had the editions of 1813 and 1815 scanned, and I thought I would show you some illustrations from both, and discuss how and why they differ. I could have included the greatly expanded 1828 edition, but that would be too much for one essay, and we might save that comparison for a later post, should this one turn out at all interesting.

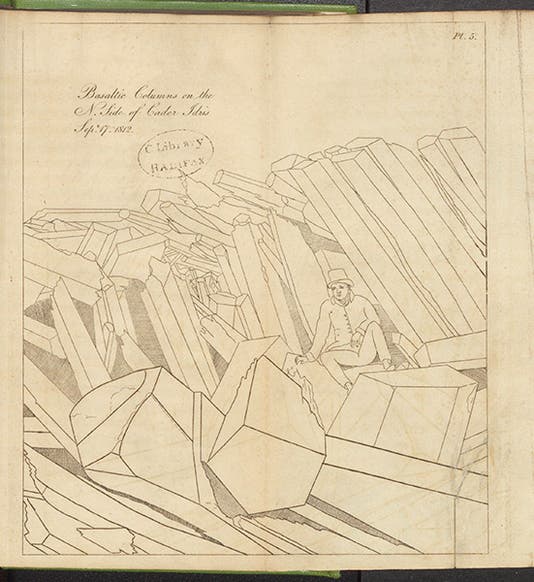

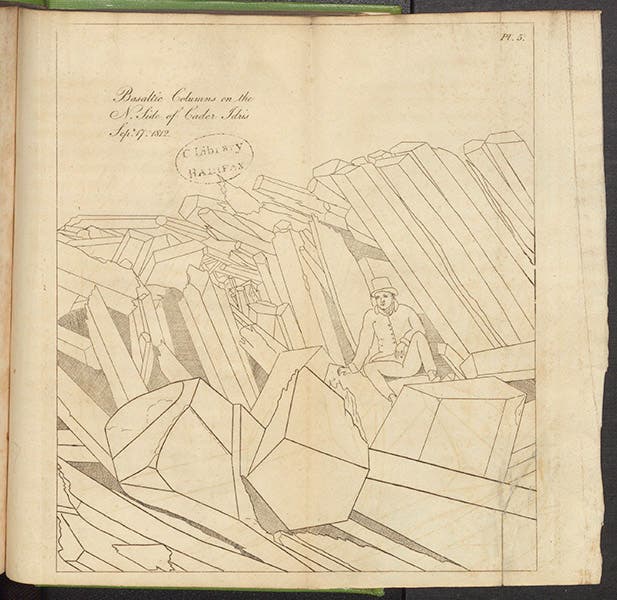

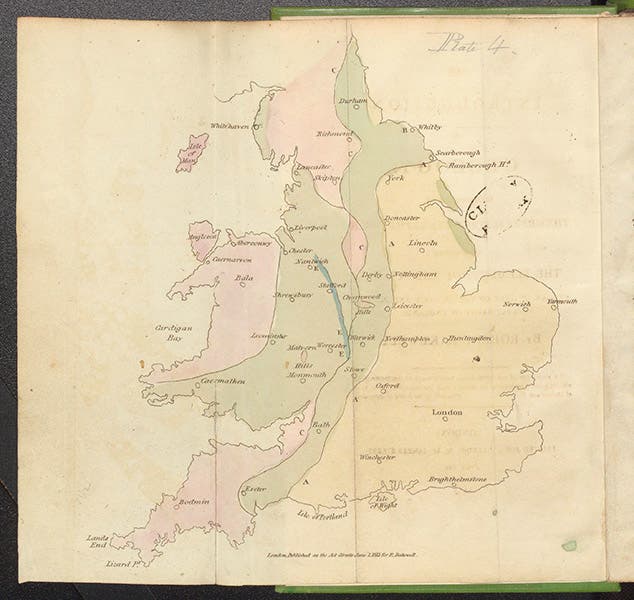

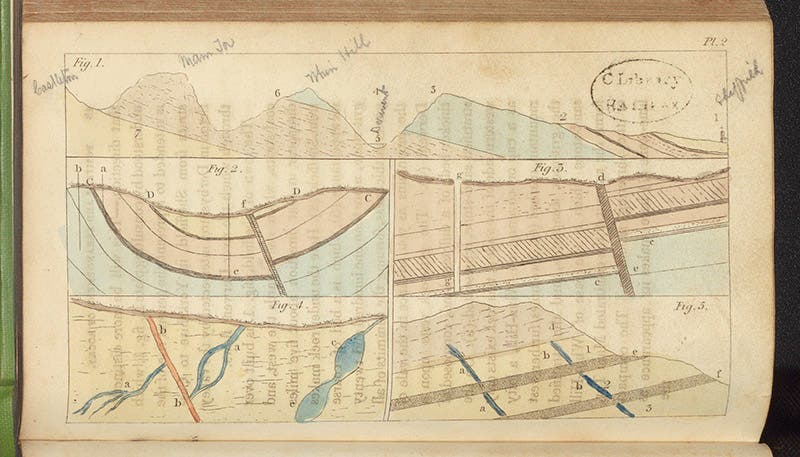

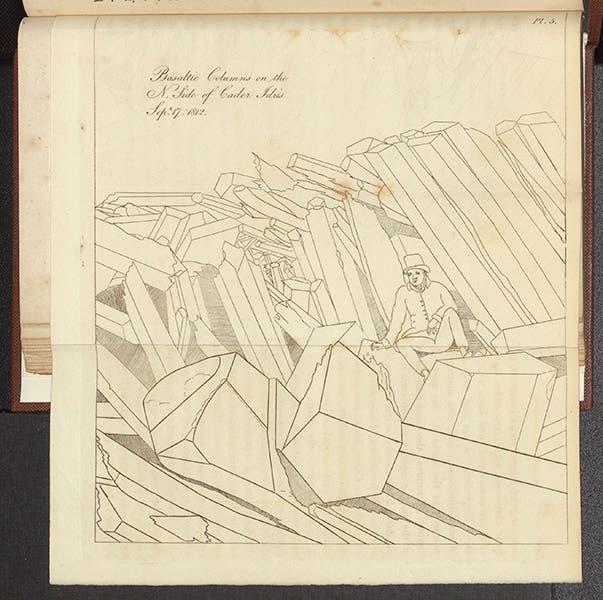

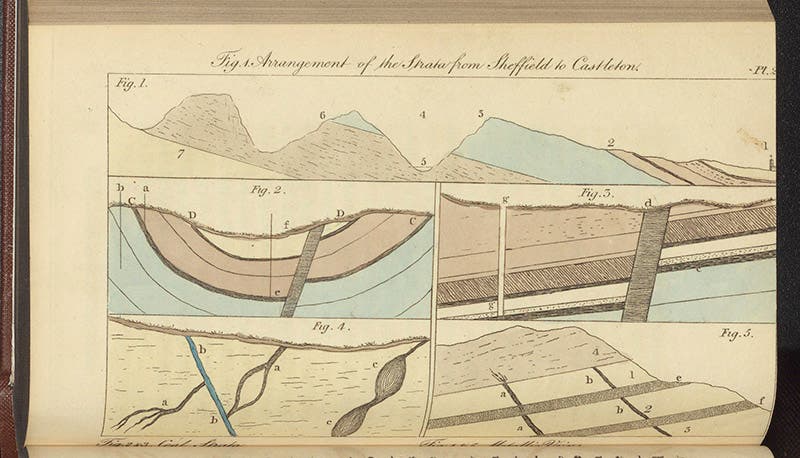

Our copy of the 1813 edition has five plates – a frontispiece geological map of England (third image), three hand-colored engravings that show geological sections at various locations in England (fifth image), and a folded line engraving that depicts an actual geologist sitting among some basalt columns on the north side of Cader Idris (an ancient mountain in northwestern Wales), on Sep. 7, 1812 (or so says the caption). The sitter is not identified, but the natural inference is that this is Bakewell himself (first image).

It struck me when I first looked at our 1813 copy that the choice of frontispiece was a curious one; geological maps were often used as frontispieces in the early 19th century, but when a map is a frontispiece, it is usually more colorful and attractive. This map (third image) is rather bland – boring in fact – and lacking a key to the coloring. One of the purposes of a frontispiece is to entice the viewer to read further, and hopefully buy the book, and this map fails by those measures. But the problem was resolved when I looked at the page that told the binder where to put the plates (fourth image). It says specifically that the dramatic Cader Idris engraving was to sit opposite the title page, and the map was to be buried opposite page 255. So our copy was simply mis-bound. This is not an uncomon occurrence – the ideal Borgesian rare book library would have two copies of every edition of every book, so missing and misplaced plates could be more easily identified.

The other thing that one notices about the 1813 edition, or at least our copy, is that the coloring of the three geological sections is dull (we show one in our fifth image). Again, this might just be a problem with our copy, but if other copies were similarly colored, there was room for improvement there.

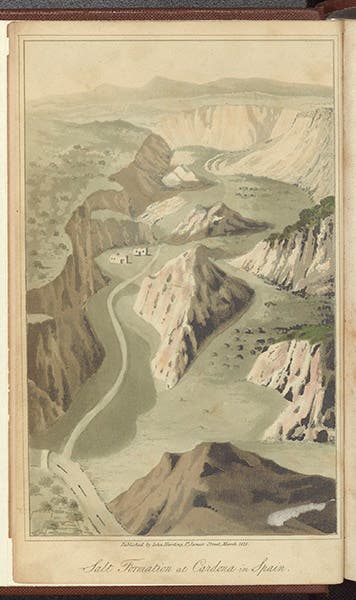

If we now look at the second edition printed just two years later, we notice some changes (see title page, sixth image). This one has two prefaces - the one from 1813, and a new one, telling you what has been improved in the second edition, and why you should buy it, even if your already have the first edition. But before you get to the preface, you will encounter and be struck by the frontispiece – it is brand new, and for Bakewell, unprecedented, in two ways (seventh image). For one thing, it shows a geological site in Spain, rather than England. Was he trying to acquire a more cosmopolitan audience? Secondly, it is an aquatint, an expensive kind of engraving that is especially suited for landscapes. There is no better way to make the point that this is a new edition than by changing the frontispiece. The previous frontispiece, the engraving of the geologist among the basaltic columns (in most copies), is moved back to page 400 (eighth image). The engraving in our second edition Is in much better condition than the identical engraving in our first edition, with its tatters and obtrusive library stamp (first image). The three engravings of geological sections are reused, but the coloring is better, and the prints are cleaner, because some effort was made to keep the text on the opposite age from bleeding onto the engraving (see the ninth image, from the 1815 ed., and compare to the fifth image, 1813 ed.). Again, this may just be a feature of our copy. But it is appreciated.

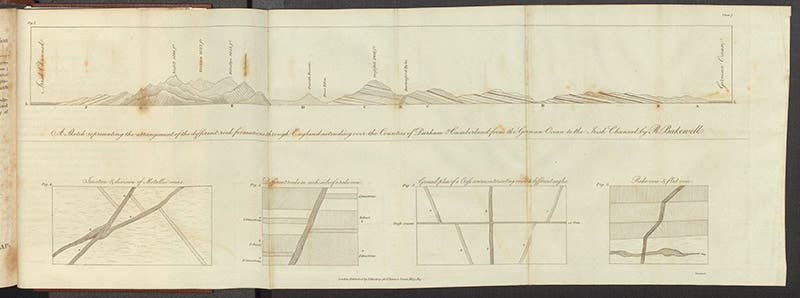

Finally, there is one other new plate in the 1815 ed., a long fold-out engraving that presents a geological section that cuts all the way across northern England, from the German Ocean to the Irish Sea, passing through Durham and Cumberland, and showing the rock formations that one encounters along the way (tenth and last image). This was what Bakewell had been doing for the two years since the first edition, traipsing across England and gathering the material for this section. This would be a major selling point for his new edition.

The later editions of Bakewell’s Introduction, starting in 1828, are much fatter, and so altered that the sub-title is changed, twice. We may have the occasion to examine these changes at a later date, and possibly look at the two American editions as well, to see if the editor, the eminent Yale geologist Benjamin Silliman, added anything to Bakewell. The Introduction sold well through the 1830s, when it was gradually replaced by Charles Lyell’s Principles of Geology (1830-33), and his more textbookish Elements of Geology (1838).

We show no portrait of Bakewill because none is known, at least to me (unless you assume the “geologist among the basalt columns” is Bakewell, which is reasonable, but unfounded). If you search Google Image, you will find lots of portraits of a Robert Bakewell seated on a horse, but that is a different Bakewell – Bakewell the sheep-breeder, about whom we have already written a post, and who is much more famous than Robert Bakewell (geologist), as we have designated him in our heading.

So to return to the questions that got us started, 1) authors reissue popular books with changes, often visual ones, to prompt owners of early editions to buy new ones, and 2) libraries with multiple editions and duplicate copies of books like Introduction to Geology are better able to allow researchers to sort out the publication history of books that go through many editions and printings. If anyone wants to tackle Bakewell in a more rigorous manner than mine, a fellowship application might be just the thing.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.