Scientist of the Day - Robert Fulton

Robert Fulton, an American inventor, was born Nov. 14, 1765, in Pennsylvania. Fulton started out as an artist, and he studied under (and lived with) Benjamin West in London for several years. While in England, he became interested in canal engineering, and he published a book in 1796, advocating the use of winches to pull canal boats up inclined planes, instead of using locks to change levels. We have A Treatise on the Improvement of Canal Navigation in our collections, as well as a French translation of 1799. Fulton’s machinery was ingenious, but his advice was not followed, as all the English canal engineers preferred canals with locks. Fulton went to Paris, where he was engaged to invent a submarine, which he did. Called the Nautilus (this was well before Jules Verne used the name for the submarine of Captain Nemo), it successfully submerged in the Seine. But Fulton was unsuccessful in getting financing to build more from the French.

However, while in Paris, Fulton met Robert Livingston, a wealthy New Yorker who had an estate on the Hudson River, between New York City and Albany. The two men were interested in building a steam-powered boat for use on American rivers like the Hudson. Fulton returned to Pennsylvania in 1806 and immediately began work on a steamboat, financed by Livingston. Several steamboats had already been built and successfully demonstrated, most notably one constructed by John Fitch, where the crude steam engine mechanically powered two banks of oars, and which huffed and puffed up the Delaware River in 1787. There were others, and patents were awarded. But no one achieved any commercial success with their steamers, which usually sank within a year or two (early steamboats were very unwieldy and unstable, since the engines were quite heavy and the boats carrying them were barely afloat).

By August of 1807, Fulton had completed a steamboat that he would call the North River (another name for the Hudson River). He designed the boat but did not build it himself; that was done by a ship-building firm, with the engine supplied by Boulton and Watt of England. It was surprisingly large for an initial craft, 150 feet long, with 15-foot paddle wheels on each side. The North River left New York City on Aug 17, 1807; reached Livingston’s estate the next morning, stayed overnight, and then went on to Albany the next day, taking some 32 hours to travel 150 miles upstream. The return to New York City, this time with a few paying passengers, was successful as well.

The reason why Fulton is usually given credit for “inventing” the steamboat, which he did not, is because he (and Livingston) made steamboat travel commercially successful. The North River paddled up and down the Hudson for years, and Fulton built improved steamboats – 17 of them in all – that revolutionized river travel in the United States. He and Livingston even built a steamboat large enough to navigate between Pittsburgh and New Orleans, within a few years of the North River’s maiden voyage. Even though Fulton died in 1815 of pneumonia and/or tuberculosis, he lived long enough to witness the transformation wrought by steam-powered river boats.

Fulton’s first steamboat is often referred to by the name Clermont, a name it never had in Fulton’s lifetime. Clermont was the name of Livingston’s estate on the Hudson, and it was first applied to the boat by Cadwallader Colden, for no reason we know of, in his biography of Fulton in 1817, a book we have in our collections. The name Clermont is often used in 19th-century accounts of Fulton, but not so much anymore. We also have another biography, The Life of Robert Fulton (1856), J. Franklin Reigart, which is rich in lithographs of the Nautilus (third image), Fitch’s unnamed steamboat (fourth image), the North River (fifth image), and several large ocean-going steamboats that made their debut after Fulton’s death. There is also a frontispiece that shows all of Fulton’s steamboats, as well as the Nautilus (seventh image). No contemporary images of any of the early steamboats survive, so the ones we have are all imagined by later artists, and probably do not much resemble the real articles, especially the North River, which certainly does not look 150 feet long in Reigart’s reconstruction. Two later versions of the North River appeared in Louis Figuier’s Merveilles de la Science (1867) which seem more faithful; we show one of those here (first image). Figuier’s visualization seems to have been the basis for a model that is on display in the Hudson River Maritime Museum (sixth image).

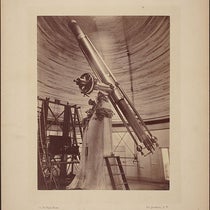

There are many portraits, busts, and statues of Fulton the man – he is as famous an engineer and inventor as the United States produced in its first century. Benjamin West painted a portrait, which is not great, and so did the dean of American portraitists, Charles Willson Peale, painted the year of the North River’s maiden voyage, and now in in the Second Bank Museum in Philadelphia (second image). Jean-Antoine Houdon sculpted a bust in 1803, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (which you can see in our post on Houdon); a copy in black marble, which I like better, was made in 1908 and can be seen in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. (eighth image). In addition, there is a full-length statue on the balcony in the reading room of the Library of Congress.

We have a modest amount of manuscript material related to Fulton that came to us from the Engineering Societies Libraries in 1995, including some autograph letters and sketches by Fulton. Perhaps in a future post we can look at these, as well as the two canal books he published while in England, which are well-illustrated.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.