Scientist of the Day - Roberto Bellarmine

Roberto Bellarmino, an Italian Jesuit and Cardinal, was born Oct. 4, 1542. Bellarmine (as the English-speaking world calls him) was the principal theological adviser for several popes, most notably Clement VIII (reigned 1591-1605) and Pope Paul V (reigned 1605-1621). Bellarmine was exceptionally well-versed in not only theology but canon law, and he knew more than the average Jesuit about natural philosophy. Like all Jesuits (indeed, like all well-educated Catholics at the time), he took, as his principal authorities, Aristotle in natural philosophy, and Thomas Aquinas in theology. Bellarmine became a cardinal in 1599, and he was immediately appointed as a Cardinal Inquisitor, meaning he sat in on Inquisition proceedings, most notably that of Giordano Bruno in 1600, whom he voted to execute when Bruno refused to recant his heretical ideas.

Bruno’s heresies were religious ones, not cosmological, but when Paolo Foscarini, a Carmelite friar, wrote and published a Letter early in 1615, claiming that Copernicanism could be reconciled with passages in the Bible that seemed to mandate a stationary Earth, if those passages were not read literally, Bellarmine sprang into action. He did so because Foscarini sent him a copy of his printed letter, plus a Defense he had written after an attack on his Letter, this sometime in March, 1615, asking for his opinion. Bellarmine replied almost immediately, on Apr. 12, 1615, stating in no uncertain terms that while Scripture could be reinterpreted to accommodate new and indubitable truths, it was premature to do so for a doctrine (Copernicanism) that had not yet been proved to be true. He also called attention to a tenet that was laid down by the Council of Trent (first session, 1545), namely, that only the highest levels of the Church could determine the meaning of Scripture; it was certainly not the province of the ordinary friar, or worse yet, a layman. We have published a post on Foscarini.

So when Galileo, in the summer of 1615, wrote a letter to the Grand Duchess Christina, the matriarch of the Medici family in Florence, claiming that Copernicanism could be reconciled with Scripture, precedent had been set, and a group of consultants was appointed by Pope Paul V to investigate the matter. They reported on Feb. 24, 1616, that the proposition that the Sun is the center of the world and does not move is formally heretical, and the proposition that the Earth moves is erroneous in faith. The next day, Bellarmine was instructed by the Pope to call Galileo to Rome and advise him of the Consultant’s report and its implications.

Bellarmine met with Galileo on Feb. 26, 1616, and Bellarmine warned Galileo about the new dangers of defending Copernicanism. This warning is called the “Special Injunction.” There is some controversy about exactly what Galileo was told by Bellarmine, because the copy of the Special Injunction in the Vatican archives is a later insertion, and possibly fraudulent. It says Galileo was told not to “hold, teach, or defend” the doctrines of a moving Earth and a stationary Sun, which would mean he could not even talk about it hypothetically. Galileo maintained that he was told only that he could not hold or defend Copernicanism, but could still treat it hypothetically. Galileo later (May 26, 1616) secured a “certificate” from Bellarmine, stating only that Galileo had been advised that he could not defend or hold Copernican ideas, but saying nothing about teaching or talking about Copernicanism hypothetically. This certificate would later play a significant role in Galileo’s trial. The De revolutionibus of Copernicus, as well as Foscarini’s Letter and a commentary on Job by Diego de Zuñiga, were placed on the Index of Prohibited Books on Mar. 5, 1616. These events, occurring in rapid-fire order, marked the beginning of what is sometimes called the “Galileo affair,” which culminated in Galileo’s Trial in 1633.

Bellarmine is sometimes castigated as one of the Bad Guys in the Galileo affair, but given the stance taken by the Church at the Council of Trent, Bellarmine’s actions and arguments were perfectly consistent with Catholic doctrine at the time. I have no doubt that, had Galileo been able to prove that the Earth moves, Bellarmine would have accepted that proof and reinterpreted Scripture himself to accommodate Copernicanism. But there was no proof, as even Galileo acknowledged. So when the Bible talks about the Earth being “established on its foundations forever,” it should continue to be read literally, until such proof is forthcoming.

At the time of his injunction to Galileo, Bellarmine was 73 years old, and he would not live to see the outcome of the Galileo affair. He died on Sep. 17, 1621. I am not sure where he was buried originally, but once the Church of Sant'Ignazio di Loyola was completed in 1650, his remains were moved there. The best known painting of Bellarmine, by an unknown artist, stands by his tomb (first image). The painting shows Bellarmine enhaloed, as a saint, and the abbreviaton “St.” stands before his name in the legend, but these were certainly added later, as Bellarmine was not canonized until 1930.

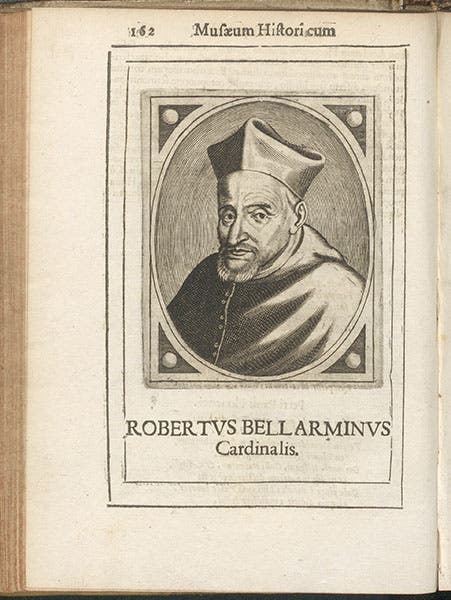

A marble bust of Bellarmine by Gianlorenzo Bernini, completed in 1624, can be seen in the Gesù in Rome, the mother church of the Society of Jesus (second image). We have several near-contemporary printed portraits in our collections; we show you one from a portrait book of 1640, the Musaeum historicum et physicum, by Giovanni Imperiali (third image). It was evidently based on the oil portrait now in Sant’Ignazio.

Dust jacket, Galileo, Bellarmine, and the Bible, by Richard J. Blackwell, University of Notre Dame Press, 1991; the dust-jacket image is from a book in the Linda Hall Library (author’s copy)

The best book on Bellarmine and Galileo is still Galileo, Bellarmine, and the Bible, by Richard J. Blackwell (1991), which may be read with profit by non-specialists. The dust jacket (fourth image) uses a photograph of the Linda Hall Library’s copy of Christoph Clavius, Opera (1612). If you would like to read the actual documents (translated) of Bellarmine, the consultants, and the Congregation of the Index, I recommend The Galileo Affair: A Documentary History, by Maurice A. Finocchiaro (1989).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.