Scientist of the Day - Roger Shepard

Roger Shepard, a cognitive scientist, was born Jan. 30, 1929, in Palo Alto. He majored in psychology at Stanford, where his father was a professor, earned his PhD in psychology from Yale, then worked for some years at Bell Labs, before returning to Stanford as a professor, where he spent his career.

Shepard started out interested in the problem of generalization – how humans and animals generalize from an experience to learn what they should or should not do. He later took an interest in spatial rotation – how are we able (or unable) to imagine what a shape will look like when rotated through space.

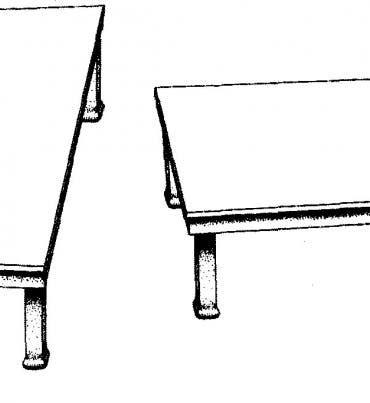

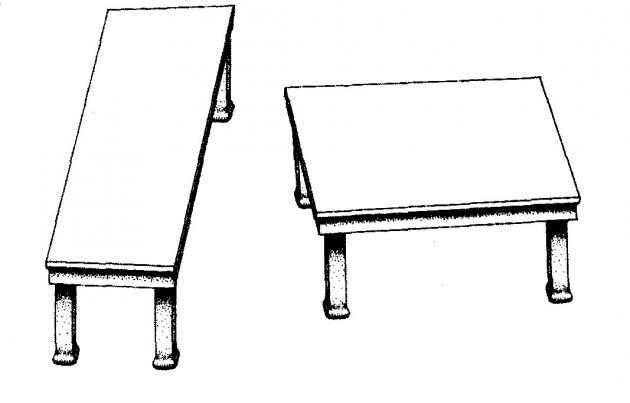

Although I find the observations of cognitive scientists fascinating, I have no expertise in the field, so for this post, I picked out two illusions devised by Shepard that we can all appreciate, even if we don’t understand how they work. The first is from the field of spatial rotation, and is called “Shepard tables”. A diagram (first image) shows a pair of tables, one seemingly long and narrow, the other more squarish. The illusion is that the two tabletops are exactly the same shape – it is our experience with perspective that makes them seem different. If you don't believe it – and I certainly did not – there are a handful of videos on YouTube that rotate one tabletop into the other. Here is a simple one, 38 seconds long without commentary, which I like, since it doesn't moralize. Search for “Shepard tables” if you would like to see others and pick up some life lessons as well.

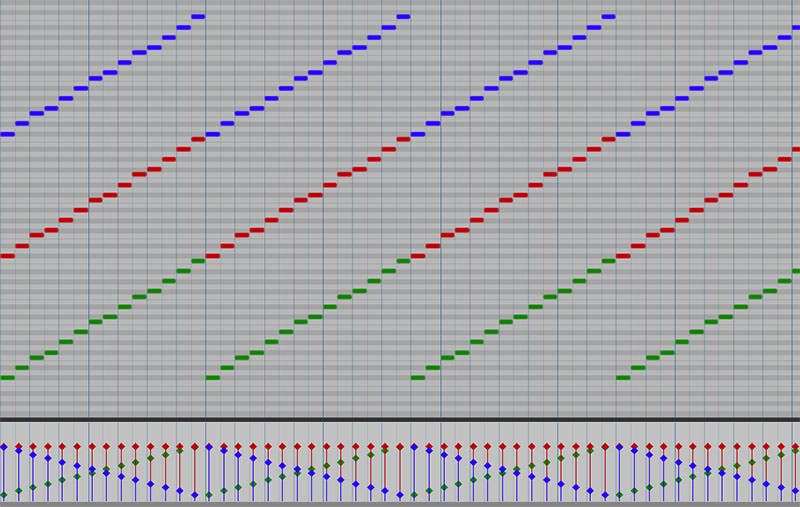

My favorite Shepard illusion is called a "Shepard tone" or the "Shepard scale." A Shepard tone is simply a chord of pure synthesizer tones that are exactly one octave apart. The loudness of each tone can be changed to alter the sound of the chord. If you now change the note, say from C to D to E, you get a Shepard scale. By decreasing the loudness of the tones as they ascend, and by introducing new tones an octave lower as the scale rises, you can produce a perception of a continuously rising scale that in fact never rises at all. It is a powerful illusion, which one cannot quite believe, even after listening to it for several minutes. I will give you an audio example in the next paragraph.

The Shepard scale is the auditory equivalent of an Escher/Penrose staircase, which seems to go up endlessly but never really goes up at all. We did a post on Maurits Escher almost four years ago, in which we showed Escher’s original drawing, and linked to a video showing a ball bouncing up an Escher/Penrose staircase, accompanied by a soundtrack, which was a Shepard scale, with the promise that we would one day offer a post on Shepard. Shepard died in May of 2022, at the age of 93, so it seems time to fulfill that promise. Here, again, is a Shepard scale, accompanying a ball bouncing up an Escher/Penrose stairway.

The Shepard scale has been used in quite a few songs and films (such as the Beatles’ I am the Walrus) to maintain the illusion of increasing intensity for a long period of time, which is otherwise difficult to do. You can see a list in the “Examples” section of the Wikipedia article on “Shepard Tone.” And this video, about the film Dunkirk, explains the illusion quite well, and also offers several examples of its use in popular music, but may not be suitable for the office, unless you set the volume quite low.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.