Scientist of the Day - Rosalie Edge

Rosalie Edge, a social activist, was born Nov. 3, 1877. Edge was a well-to-do New York socialite, active in the women's suffrage movement, and a late-in-life birder, but she was otherwise unremarkable, until the day in Paris in 1929, when she received a pamphlet titled "A Crisis in Conservation," written and self-published by Willard Gibbs Van Name, a zoologist at the American Museum of Natural History. It pointed the finger at an unnamed organization, accusing them of pandering to the interests of hunters and trappers in allowing the indiscriminate slaughter of birds and fur animals. The target however was unmistakable: the National Association of Audubon Societies, the forerunner of today’s Audubon Society.

Edge came back to New York, met Van Name, and they formed a group, the Emergency Conservation Committee, with Edge as president. Two months later, she walked into the annual meeting of the Audubon Society and demanded that the directors answer the accusations made in the pamphlet, much to the consternation of all present, since usually the annual meeting was a well-met and good-old-boys affair. Nothing came of that first encounter, but when Van Name was forbidden by his superiors at the Museum from publishing any more attacks on the Association of Audubon Societies, Edge became publisher and distributor of a whole series of Van Name pamphlets. She attended the next annual meeting and demanded the mailing list of the Association, and when they refused her, she found a young, conservation-inclined lawyer, took the Association to court, and won. Soon all the Association of Audubon Societies members were received regular mailings pointing out the misdeeds of its directors, who were indeed conniving in an underhanded way with the sport-hunting industry. It took a few years, and a drastic plunge in membership, but by 1934, the president resigned, and the directors were voted out and replaced by a slate that was indeed devoted to conservation, and the Audubon Society that we know today emerged. The transformation was entirely due to Edge and her behind-the-scenes partner, Van Name, and their thousands of supporters.

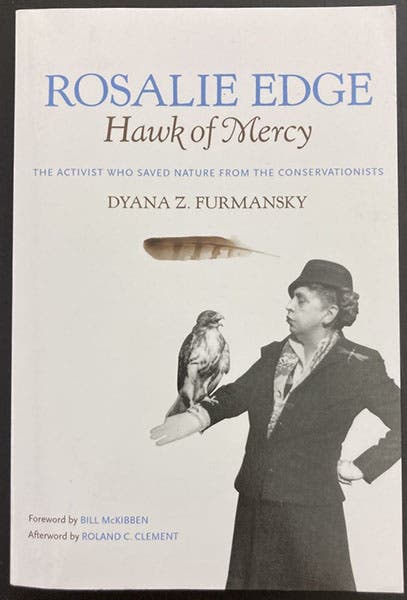

In 1933, Edge was shown some photographs of the flanks of Hawk Mountain in eastern Pennsylvania, littered with the bodies of thousands of raptors that had been slaughtered by hunters during the annual migrations. Outraged again, Edge went to Hawk Mountain, leased some 1300 acres, and installed a 24-hour warden, who, with his wife, had the unpleasant task of telling armed hunters that shooting hawks was no longer allowed on the property. The next year, using money advanced by Van Name, she bought the property and turned it into a sanctuary. Hawk Mountain Sanctuary is still thriving; here is their website. I remember when my Dad, an avid birder, drove our family down there from Connecticut to see the annual hawk fly-by, and it was indeed an enthralling sight, for us and hundreds of other wildlife enthusiasts. There was a photograph taken in 1947 of the saucy Rosalie Edge with a hawk on her arm (first image), and Hawk Mountain Sanctuary today uses it as the logo for their most prestigious donor society. When one thinks of the uninspiring names and logos that are often given to donor groups, the Rosalie Edge Society is a refreshing exception.

Rosalie had more arrows in her quiver. She took on the National Park Service, which had a tradition of kowtowing to the National Forest Service and powerful lumber interests, so that places like Olympic National Monument had large swathes of former timber stands that had been clear-cut, with government approval. She was one of the major forces in transforming Olympic into a National Park in 1938, with timber removal forbidden, and she followed suit with Kings Canyon National Park in central California. She continued to crusade, and preside over the Emergency Conservation Committee, until her death in 1962, at age 85. When one considers that she was 52 years old when she walked into that Audubon Society meeting in 1929, we realize that she accomplished all this when most of her social peers were getting ready for or well into retirement. Rosalie Edge was America’s first great woman conservationist, paving the way for equally remarkable women like Rachel Carson.

Front cover, Rosalie Edge: Hawk of Mercy, by Dyana Z. Furmansky, Univ. of Georgia Press, 2010 (author’s copy)

There is an excellent, fairly recent biography of Rosalie Edge, by Dyana Furmansky, called Rosalie Edge: Hawk of Mercy: The Activist who Saved Nature from the Conservationists (2009; fifth image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.