Scientist of the Day - Rowland Hill

Rowland Hill, a Victorian political economist and social reformer, was born Dec. 3, 1795. In 1837, Hill published a pamphlet, Post Office Reform its Importance and Practicability, in which he proposed that the postal system in England needed to be reformed and then specified in detail what that reform should be. Although his ideas were widely ridiculed and criticized, Hill had a persuasive air about him, for in 1839, Parliament passed a bill turning Hill's proposed reform into law, and the new system was implemented on Jan. 10, 1840.

Before the 1840 reform, postage rates for a letter in England were based on the size of the letter (number of sheets) and the distance the letter was to travel, and the fee was collected after delivery, from the recipient. It could easily cost 8 pence to send a letter across England, which was more than most people could afford; in consequence, letters were few, and revenue was low. Hill's idea, which was grounded in years of careful research, was that there should be a flat rate for a letter, namely one penny, which would be paid in advance, and would send any letter up to 1/2 ounce anywhere in England for the same flat one-penny fee. Payment of the fee would be indicated by an adhesive sticker, to wit, a postage stamp, applied to the letter. Hill even recommended that, to prevent counterfeiting, the stamp should contain the one image that is almost impossible to copy faithfully--the human face--and suggested that the face of Queen Victoria would be appropriate.

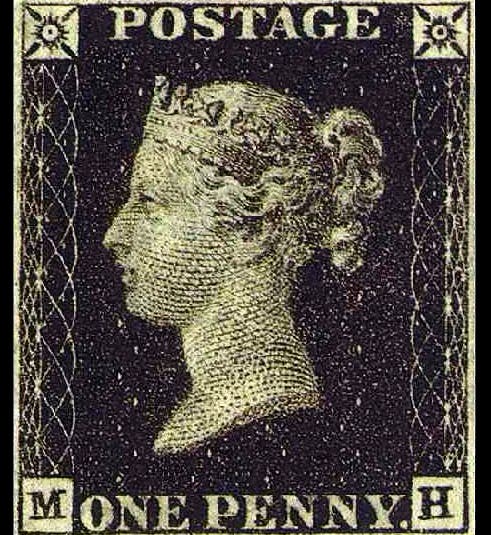

The first penny blacks, as the stamps were called, were issued in May of 1840, and Queen Victoria looked pretty good, but then she was not yet 21 years old (first image). Most postage albums have a spot for the penny black, on page one, line one, slot one, since it was the world's first adhesive postage stamp. The space is usually empty, unless you had a great-great-great grandfather who knew a good penny investment when he saw one.

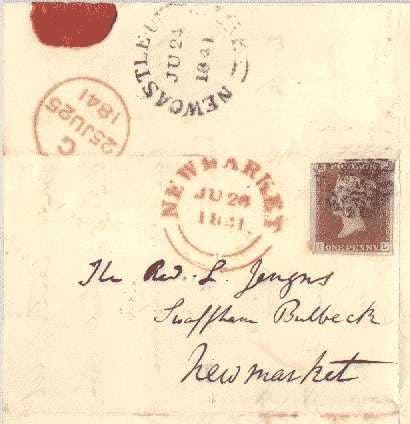

Redesigning the postal system, inventing the penny post, and introducing the postage stamp, all in one fell swoop, was a most impressive achievement by Sir Rowland, but it was not, strictly speaking a scientific feat. It merits inclusion here because of Charles Darwin. No one made better use of the penny post than Darwin (second image), and it has been often argued that Darwin's career would never have developed as it did without the penny post. In 1840, Darwin was four years back from the Beagle voyage, recently married (1839), had just published his narrative of the voyage, and was about to tackle the specimens he had saved for himself, when he got sick. Suffering spells of vomiting and anemia that would dog him to his dying day, he retired from social circles, shut himself off in his study, and began communicating by mail. The implementation of the penny post was perfectly timed. Darwin wrote letters incessantly; he wrote business letters, personal letters, politically necessary letters, and, most of all, he wrote letters of inquiry to fellow naturalists, asking for a barnacle here, a seed there, seeking help in answering questions and solving problems. This correspondence network was as responsible as anything Darwin did in building his reputation within the scientific community and establishing ties and obligations. Darwin wrote some 15,000 letters during his lifetime, and writing them required thousands of hours of Darwin's time. Mailing them, however, only set his pocketbook back the grand total of 62 pounds sterling. What a bargain! If Darwin was not the one who proposed a knighthood for Hill, he should have been.

There are at least seven plaques of various colors scattered about England honoring Rowland Hill; we show a brown one on the house in Sutton where he resided for the last 30 years of his life. There are also three statues of Hill, and an oil portrait in the National Portrait Gallery in London, made at the time of his death in 1879, from an 1857 photograph. It is eerily compelling, given that it was not painted from life.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.