Scientist of the Day - Rubens Peale

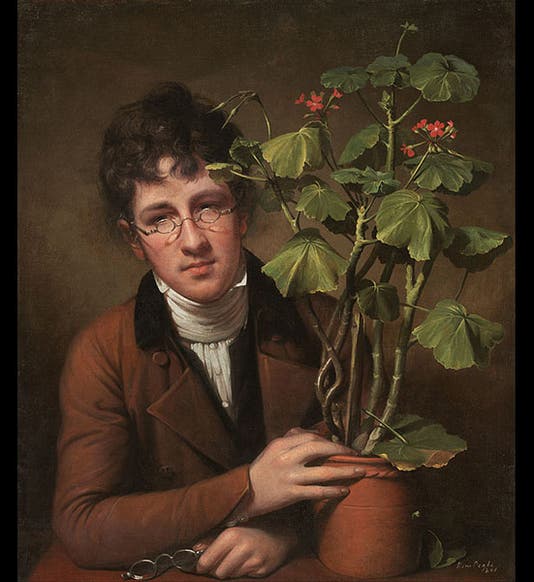

Rubens Peale, an American painter and museum administrator, was born May 4, 1784. Rubens was the son of Charles Willson Peale, the noted portrait painter, naturalist, and founder of Philadelphia's Peale Museum. His two older brothers, Raphaelle and Rembrandt, were accomplished artists, as was the much younger fourth brother, Titian, who was an explorer as well. Rubens was the odd duck in this famous filial foursome, and you can see why if you look at a portrait of Rubens by Rembrandt, painted in 1801 (first image). Take your eyes off the geranium for a moment and look at what is perched upon Rubens' nose. Glasses were so cumbersome and awkward in the late 18th century that no one wore them unless they really could not see without them. It was Rubens’ poor eyesight that prevented him from following in his father's and brothers' footsteps as a portrait painter.

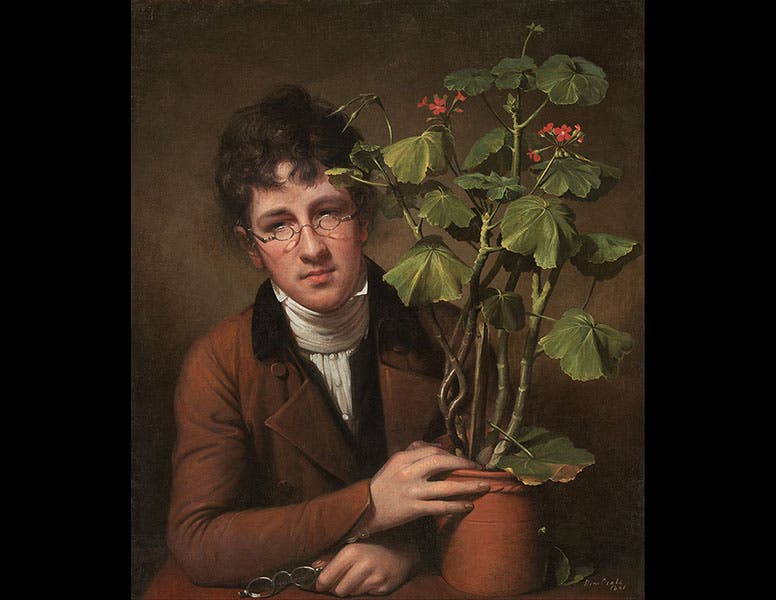

Instead, Rubens went into management, running the Peale Museum in Philadelphia for some years, then the Peale Museum in Baltimore (with Rembrandt) for quite a few more, and finally his own museum in New York City. Since all three museums folded by mid-century, Rubens’ administrative skills were apparently less than outstanding. He finally retired to his father-in-law’s farm in rural Pennsylvania in the 1850s, and in the last several years of his life, he gave in to his genes and started painting, turning out over a hundred works of art, most of them still lifes. They are quite collectible, perhaps because they can be obtained much more cheaply than any work by Rembrandt, Raphaelle, or Titian Peale. You can see 13 of his late-in-life paintings on The Athenaeum website, one of which, Still Life with Watermelon, we have reproduced above. Rubens painted this one right before his death, when he was 80 years old. I am sure he couldn’t see any better when he was 80 than when he was 20. But no doubt he simply didn’t worry about that any more, and that can make a world of difference.

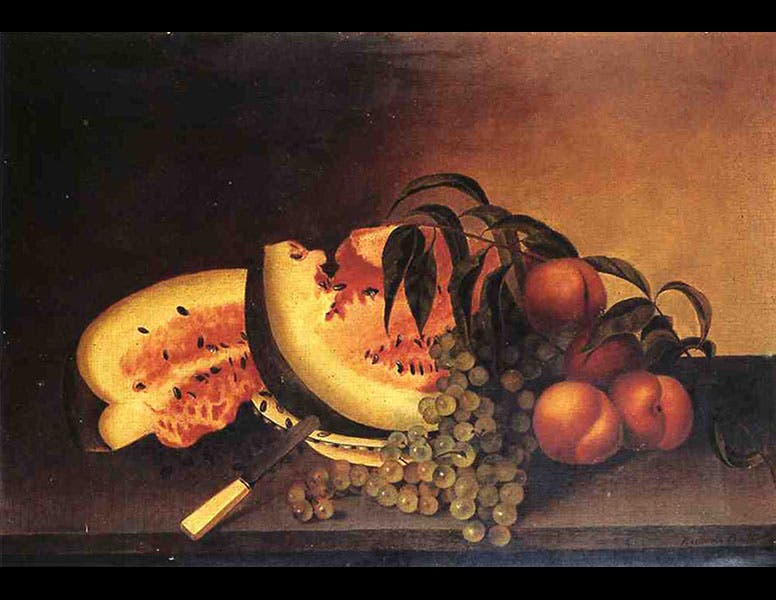

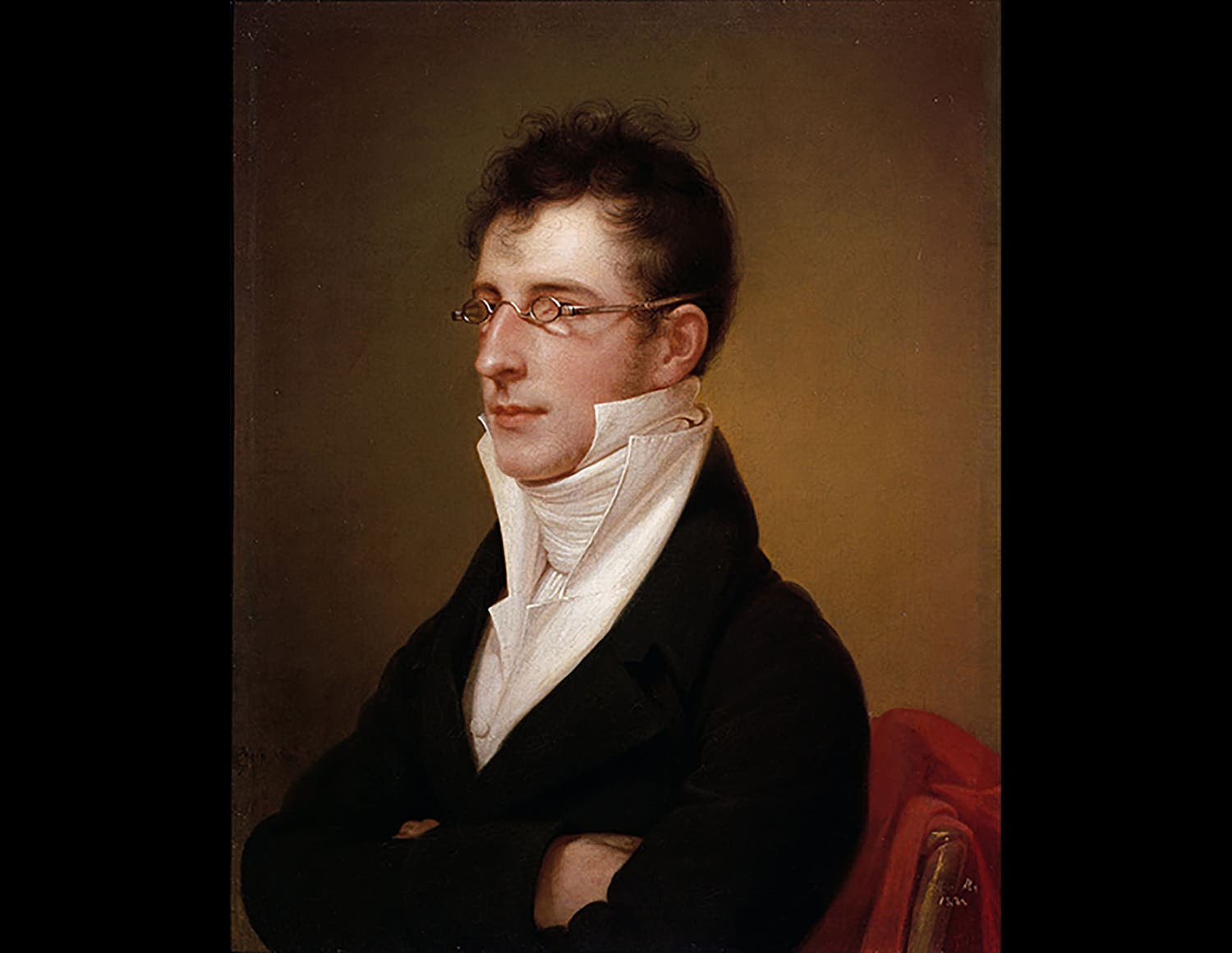

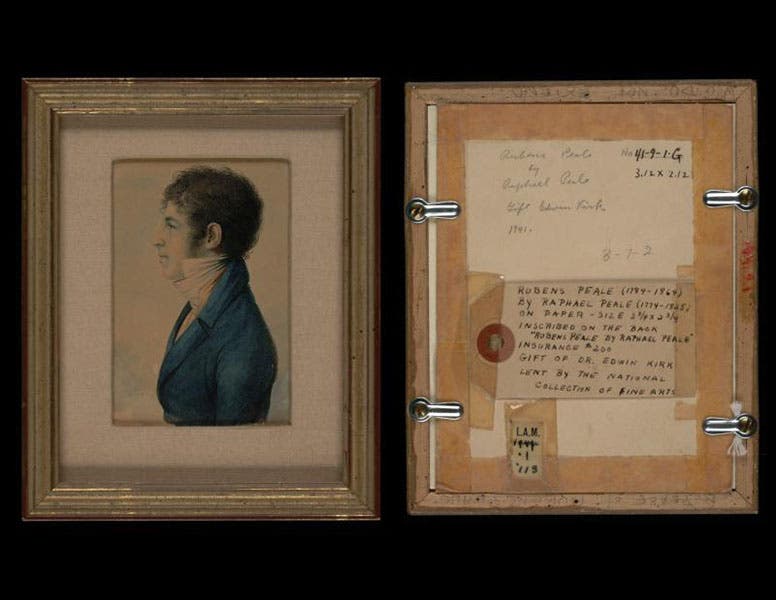

So Rubens was not especially successful as a business manager or a painter. But as a sitter, he was dynamite. The portrait with a geranium by Rembrandt has become quite well-known, in part because Rubens actually grew the plant depicted in the painting, and it was the first geranium cultivated in the United States. The painting so appealed to curators at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. that they bid over $4 million for it in 1985, at the time a record auction price for any piece of American art. Rubens sat for another portrait by Rembrandt in 1807, glasses still in place (third image); this one is in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington. Raphaelle painted a miniature pastel of Rubens around 1800, now in the Smithsonian American Art Museum (fourth image); for this one, the eyeglasses were parked elsewhere. In the same museum, there is a fourth portrait of Rubens, also a miniature, by his cousin, Anna Claypoole Peale (fifth image). It was painted about 1822, and as you can see, the glasses are back.

Portrait sitting is a passive art, but it is an art nevertheless, and Rubens Peale was very good at it. It was, in fact, his quintessential skill.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.