Scientist of the Day - Simon Stevin

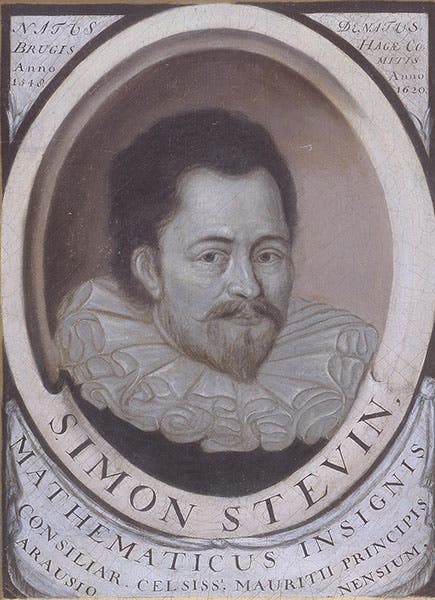

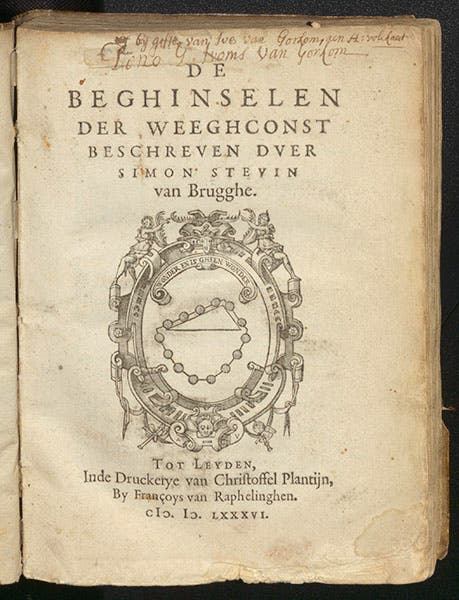

Simon Stevin, a Dutch mathematician, physicist, and engineer, was born in Bruges in 1548 and died in 1620; we have no exact birth or death dates. After some travelling, he enrolled at the University of Leiden in 1583, at a rather late age for the time, and there he met Prince Maurits of Nassau, who would later rule Holland and would employ Stevin in various capacities. Before he graduated from Leiden (actually, he never did graduate), he published 5 ground-breaking works in mechanics and hydraulics, gathered up in one volume. The two we will look at here are called De Beghinselen der Weeghconst (Elements of the Art of Weighing, the first treatise in the volume) and De Beghinselen des Waterwichts (Elements of Hydrostatics, the third treatise).

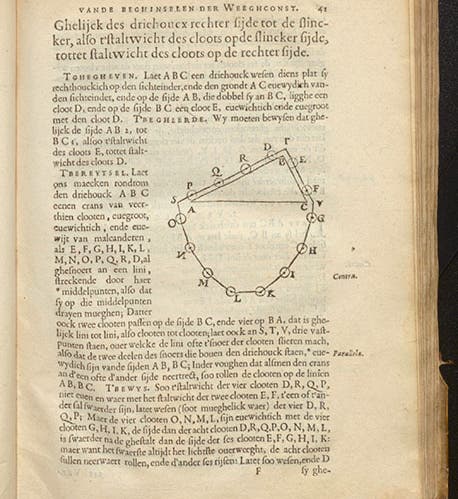

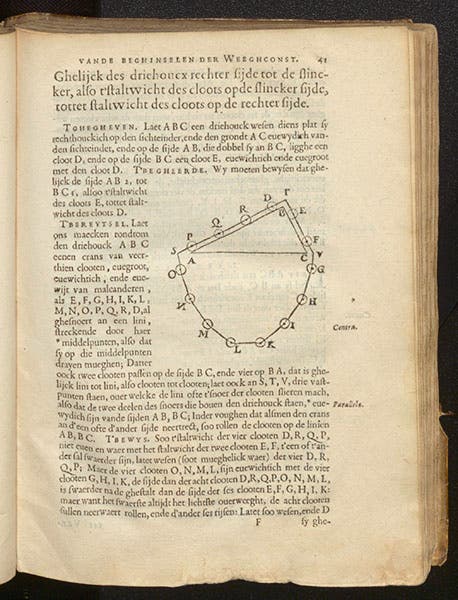

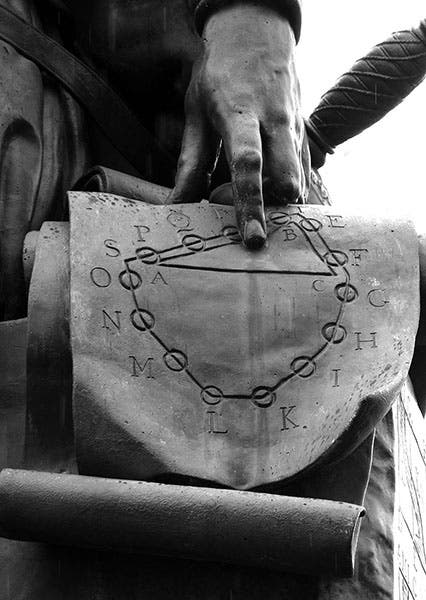

Stevin was one of the many revivers of Archimedes in the late Renaissance who set the stage for Galileo's work in mechanics and hydrostatics. In his book on the art of weighing, Stevin considered the problem of determining the effective weight of a body on an inclined plane, and he solved it with one of the most ingenious thought experiments in the entire history of mechanics. Imagine a wreath of spheres (14 in this case, see first image) straddling two inclined planes, one at an angle of 30°, the other 60°. The plane at the shallow angle will be twice as long as the steeper plane, since they form two of the sides of a right triangle, so there will be four spheres on the long side and two on the short side. Now clearly the wreath is in balance – if it were moving, it would be an example of perpetual motion, which Stevin thought absurd. If it is in balance, then we can remove the bottom 8 spheres, since they cancel each other out, and we are left with 4 spheres balancing 2 spheres, which means the two spheres on the steep plane each have an effective weight twice as great as each of the four spheres on the shallow plane. Effective weight goes up in proportion to the angle of inclination. What a brilliant way to derive that result!

Stevin was proud of his wreath of spheres and used it as the titlepage vignette for all of his 1586 treatises (third image). Much later, the editors of the prestigious Dictionary of Scientific Biography (1970-80) used Stevin's wreath of spheres as their own device, stamping it on the front cover, spine, and all four endpapers of of each of the 16 volumes of the set (fourth image).

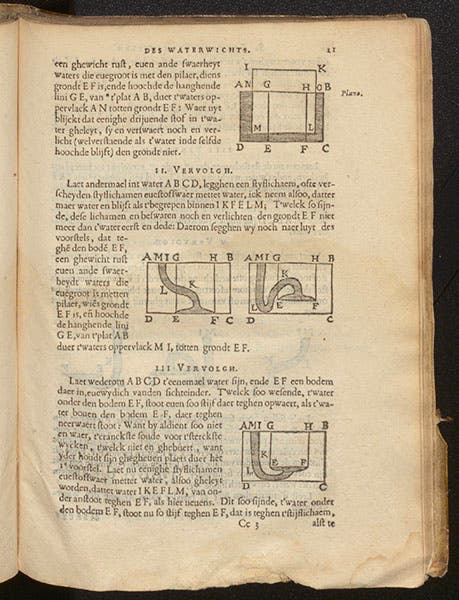

In his Elements of Hydrostatics, Stevin not only demonstrated the truth of Archimedes' law determining the loss of weight of bodies immersed in water, but he discovered new principles of his own. For example, he imagined a variety of oddly shaped water vessels and asked how the shape of the vessel affects the water pressure at the bottom (fifth image, below). He concluded that the shape makes no difference – the water pressure depends solely on the area of the bottom surface and the height of the column that lies above. If those quantities are the same in four differently shaped vessels, then the water pressure will be the same in all four cases. This was 60 years before Blaise Pascal, more famously, came to the same conclusion.

Stevin is also noted for having dropped objects of different weights but the same material from a height of three floors and observing that they struck a board at the same time, contrary to Aristotle, who claimed that heavier objects fall faster. This was well before Galileo even thought about (but not did carry through on) dropping similar objects from the top of the tower of Pisa, with the same goal, to show that Aristotelian conclusions about falling bodies are incorrect.

On at least one occasion, Stevin came to wider public notice, when he designed and had built two “land yachts” for his friend, Prince Maurits of Nassau, which they would race across the beach. There is an engraving of one of these sand regattas by Jacques de Gheyn, reproduced on Wikipedia, but that version was almost certainly colored much later. We prefer an uncolored engraving by Willem Isaacsz. van Swanenburg, made in 1602 (sixth image).

Stevin died in 1620, which means he lived to see Maurits become Prince of Orange in 1618. A statue for Stevin was erected in Bruges in 1846, sculpted by Eugène Simonis, and sitting at the center of a square named after Stevin. With his left hand, the bronze Stevin points to a drawing of the wreath of spheres (eighth image). Just behind the wreath is a surface that illustrates two of the water pressure diagrams in our fifth image (ninth image). I saw the Martin McDonagh film In Bruges (2008) many years ago, but don’t recall noticing that the Stevin statue made an appearance in the movie. If it did, I hope some knowledgeable reader will let me know, so I can seek out that scene again.

All of Stevin’s works were translated into English and published in 6 volumes as Principal Works (1955 to 1966; yes, the wreath of spheres provided the embossed cover device for each volume of this set too). Most Stevin scholars use this edition, understandably, since Dutch is not a widely read language outside the Netherlands. But it would be a shame if the original Dutch editions were not consulted as well, especially for the diagrams, which speak a universal language, and two of which we have reproduced here.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.