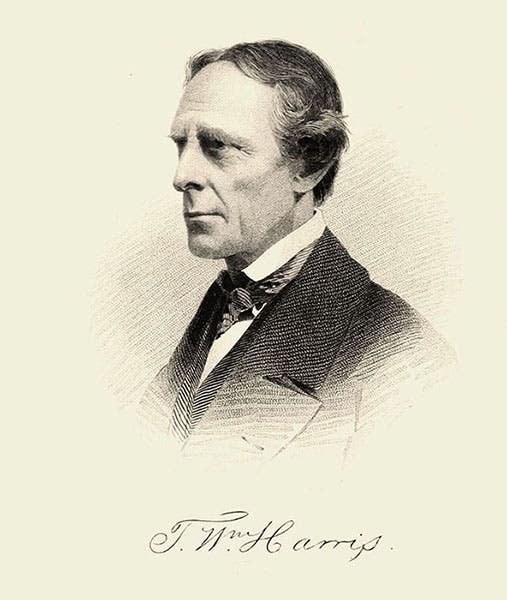

Scientist of the Day - Thaddeus William Harris

Thaddeus William Harris, an American entomologist and librarian, was born Nov. 12, 1795, in Dorchester, Mass. (now part of Boston), the son of a Unitarian Minister. He went to Harvard College, where he attended the classes of William Dandridge Peck. Not only was Peck one of the first native-born naturalists in this country, he was also one of the first entomologists to study the effects of insects on farming and on human populations, thereby founding what we call agricultural entomology and economic entomology, and having a profound effect on young Harris.

Harris received his medical degree from Harvard and practiced medicine for some years, while pursuing insect studies in his spare time. His father had been Harvard College librarian for a few years back in the 1790s, and when the post became vacant in 1831, Thaddeus William was offered the position, and he accepted. He also gave natural history lectures at Harvard, but he was never admitted to the regular faculty.

In 1837, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts authorized a Zoological and Botanical Survey, to catalog the animals, plants, and insects, and their impact on the state. Harris was appointed to the Commission to prepare a report on insects, especially on their impact on agriculture. This was right up his alley, and his book was published in 1841, as A Report on the Insects of Massachusetts, Injurious to Vegetation. We do not have this 1841 edition in our Library, which surprises me, since one would have thought that the library of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in Boston would have acquired it, and the Academy Library is now part of our library. But the report is not here.

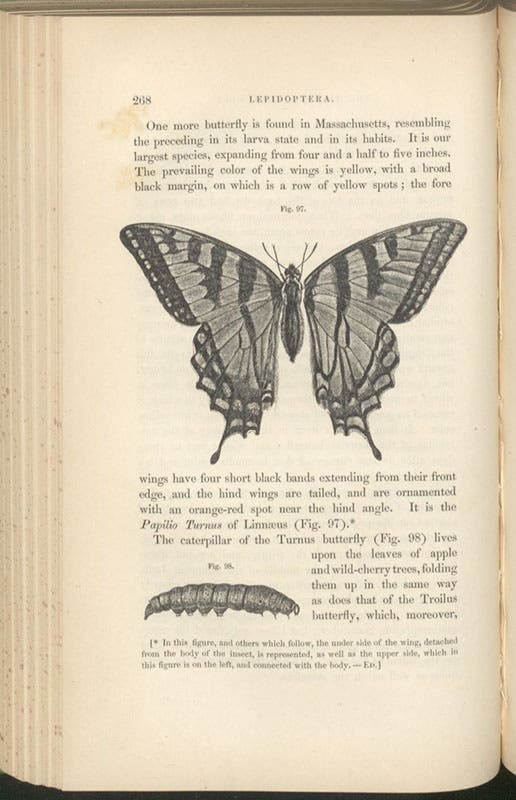

Fortunately, the book was desirable enough to warrant a second edition, which Harris edited and published in 1852. We do have a copy of this second edition. But it is not much to look at, since neither the first nor second editions has a single illustration.

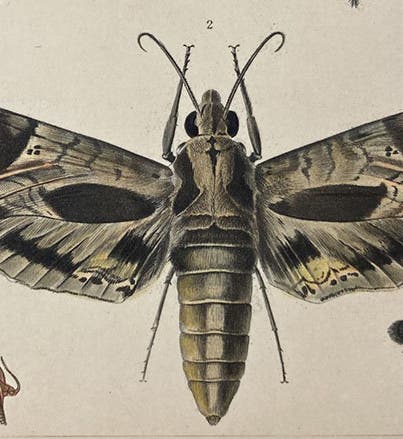

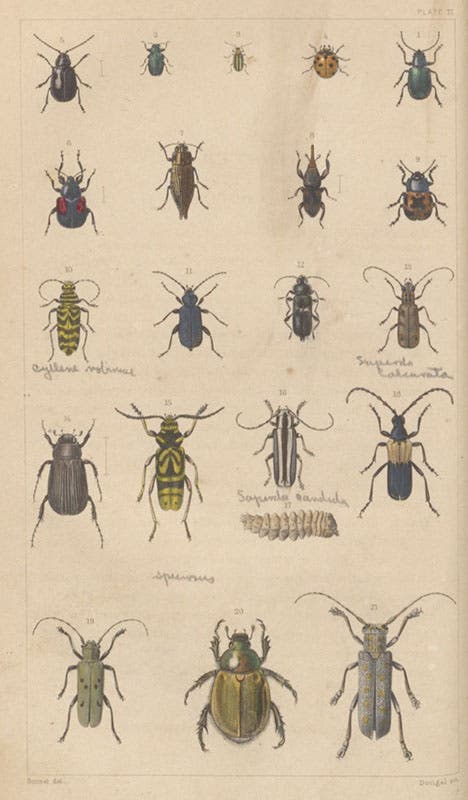

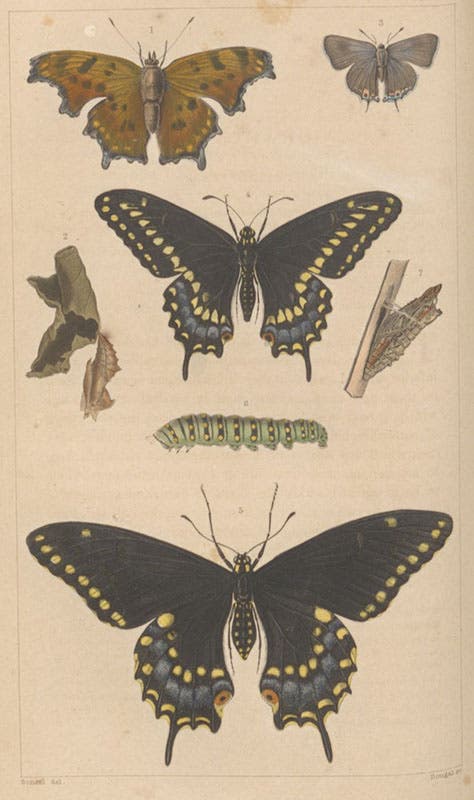

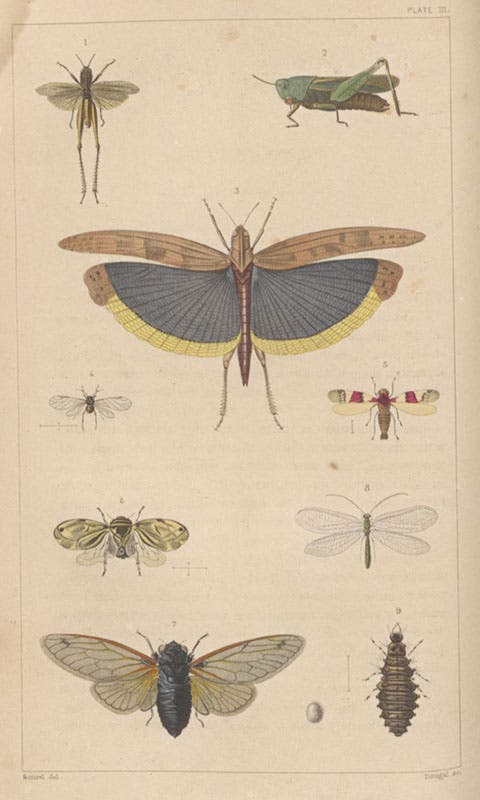

In 1861, the state ordered a third edition, this time authorizing the expense of illustrations. Harris had died in 1856, so he had no role in providing the plates or text images – these were farmed out to two artists and two engravers by the editor, Charles Flint, who however took care to have each image vetted by naturalists at Harvard, including Alexander Agassiz. The result was Harris’s text, now studded with scores of wood engravings, and accompanied by 8 hand-colored, steel-engraved plates, each with a dozen species or so. I have used images from our copy to illustrate this essay.

Curious as to what Harris might have to say about injurious insects, I opened to the section on the clothes moth, a member of the genus Tinea. Harris described the life-cycle of a clothes moth, how the moth-worm does its damage in late summer and early fall, when it goes dormant until spring. It then forms a chrysalid, pupates, and hatches into a moth, which then lays eggs for the next generation. Then comes the best part: advice to the "prudent housekeeper," who in early June should empty all the bureaus and cupboards, put all the woolens out in the sun, thoroughly clean and dust the drawers, and give everything a good shaking before putting the clothes back, preferably with a little camphor or bits of tobacco leaves folded in. If all the advice was as practical as this, Harris had performed a great service for his readers. One hopes he had readers.

I would not have thought that Harris would merit a full-blown biography, except perhaps as a PhD thesis, but I underestimated the camaraderie of former Harvard college librarians. Clark Elliott was a recent librarian at Harvard before becoming Director of the Burndy Library when it was in Cambridge, and he published a thorough biography of his predecessor at Harvard, called Thaddeus William Harris (1795-1856): Nature, Science, and Society in the Life of an American Naturalist (Lehigh University Press, 2008), which we have in our collections, and was my primary source for this piece.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.