Scientist of the Day - The Diamond Sutra

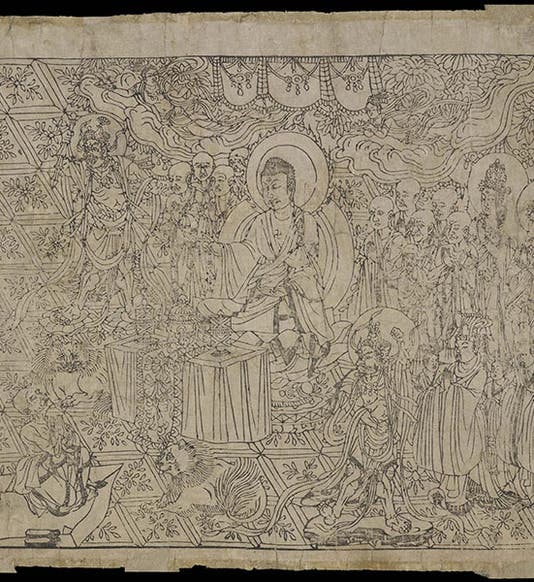

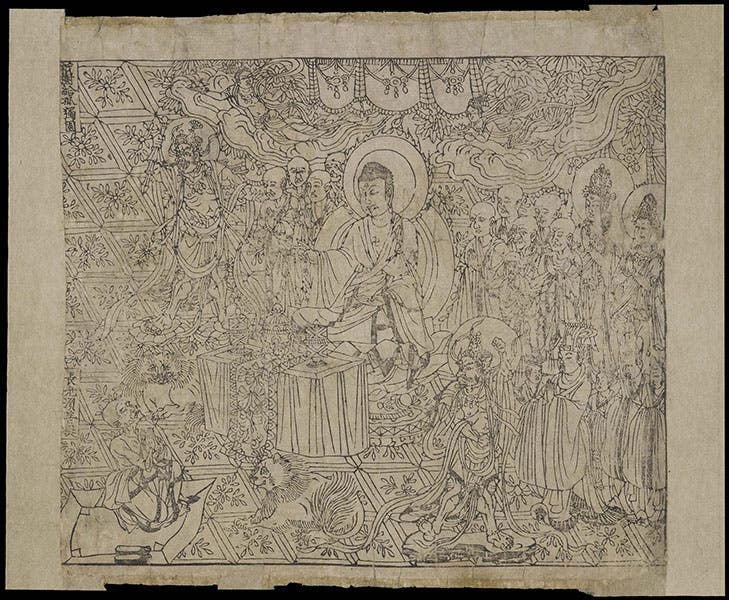

On May 11, 868 C.E, a Chinese scribe named Wang Jie published an edition of a Buddhist text known as the Diamond Sutra. The text was carved onto a number of woodblocks, with a woodblock frontispiece at the beginning depicting the Buddha (first image), and then printed on 7 sheets of paper that were glued up into a scroll about 16 feet long. The text ends with a colophon that says: "On the 15th day of the 4th month of the 9th year of the Xiantong reign period, Wang Jie had this made for universal distribution on behalf of his two parents” (second image). Because Wang Jie included the date (May 11, 868 C.E. in the western calendar), this copy of the Diamond Sutra is the oldest complete dated printed book known in the world. Today is its 1,155 birthday.

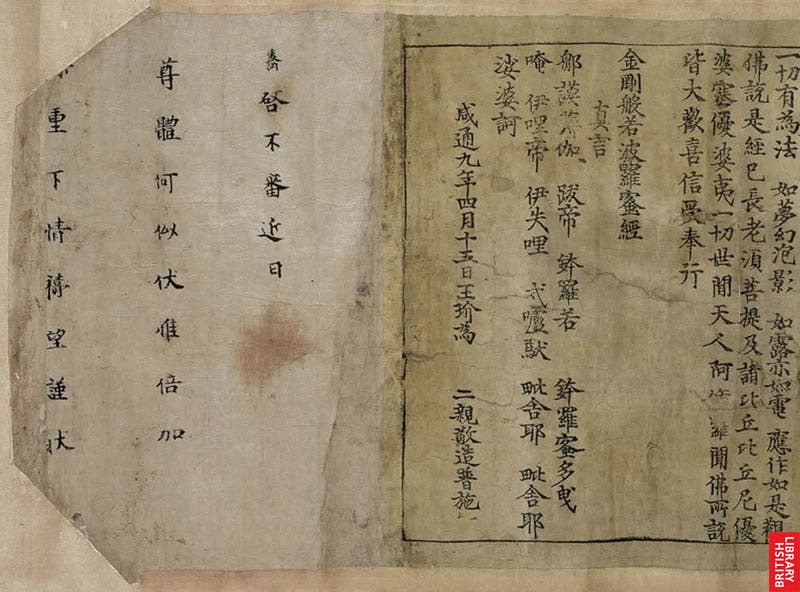

Sometime before 1000 C.E., the Diamond Sutra and thousands of other Buddhist manuscripts were sealed up in a cave near Dunhuang in northwest China, along the old Silk Road. The cave is one of nearly 500 caves that were dug out of a one-mile stretch of soft rock by Buddhist monks. Today it is called the Mogao Cave complex. Photos of Mogao usually show a pagoda that was built on the cliff face, but that was not part of the original complex, and we show instead a view along the walkway that now connects the caves (third image). Many of the caves are richly decorated with Buddhist wall paintings and sculptures. Cave 17 was the one that contained most of the manuscripts, including the Diamond Sutra; it had been carefully sealed, provided with a secret entrance, and as far as we can tell, was unopened for the next 900 years.

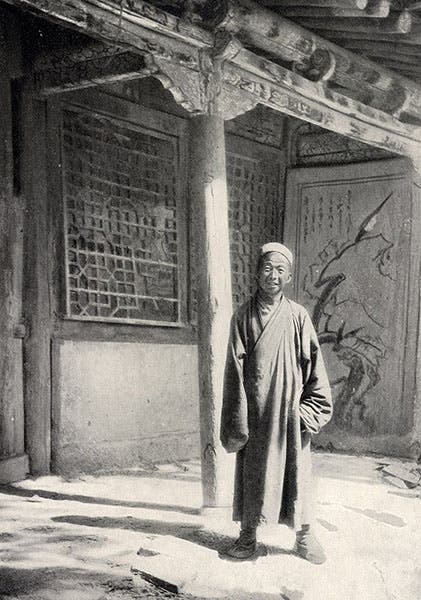

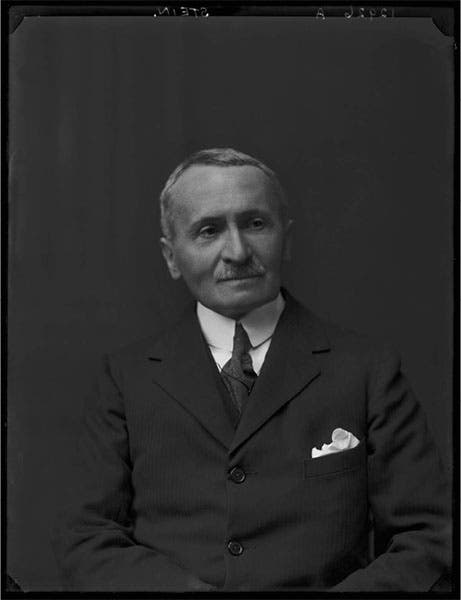

The Library Cave, as it is sometimes called, was found around 1900 by a Taoist monk, Wang Yuanlu, who was also the first to discover many of the other caves, and who apparently appointed himself curator of the complex (fourth image). The cave was visited in 1907 by Hungarian-born British archaeologist Aurel Stein, who was quite well-known as an explorer of central Asia. Stein took a photograph of Cave 16, with many of the scrolls from Cave 17 piled up on the floor (fifth image). He persuaded Wang Yuanlu to sell him many of the manuscripts from Cave 17, including the Diamond Sutra, which then travelled back to England, and eventually into the British Library, where it is one of their designated treasures. Western historians are not sure how to view Aurel Stein (sixth image), who played a role in removing a Chinese national treasure from the country where it was found, and Chinese historians have considerably mixed feelings about Wang Yuanlu, who discovered a magnificent site but was complicit in selling much of its legacy to foreigners.

Printing was practiced in China long before Johannes Gutenberg devised his system of moveable type and printed his Bible around 1455. The Chinese learned how to carve designs and text onto flat wooden blocks as far back as the Han dynasty, which ended in 220 C.E., and the oldest surviving examples of woodblock printing are some fragments of printed textiles that go back to around that time. By the time of the Tang dynasty in the late 7th century, sutras (Buddhist texts) were being printed from carved woodblocks in China, and by 800 the practice had been introduced into Korea and Japan. Many printed specimens have survived from this era. What makes the Diamond Sutra special is that it is complete, and it is precisely dated.

You may view the Diamond Sutra on the British Library Website, where it is presented in 12 separate sections, each with its own commentary. Here is the link. The general home page for the Diamond Sutra may be found here.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.