Scientist of the Day - The Montgolfier Brothers

Just before 2:00 PM, on Nov. 21, 1783, the first untethered manned balloon ascended from the Jardin de la Muette near the Seine in Paris and headed skyward. The balloon had been built by a pair of paper-manufacturing brothers, Étienne and Joseph Montgolfier. The two had been aiming toward a free ascent of a human-occupied balloon for just about a year, and the first 10 months of 1783 saw significant progress. In June, they had successfully launched an unmanned balloon. In September, they released a balloon from Versailles with three occupants, but they were not people. Instead, a rooster, a duck, and a sheep occupied the basket. They survived the flight, although the sheep broke the rooster's wing. In October, a man named Jacques-Alexandre Pilâtre de Rozier made three tethered ascents in a Montgolfier balloon, anchored to the Earth by 300-foot ropes. The time for a free ascent seemed at hand.

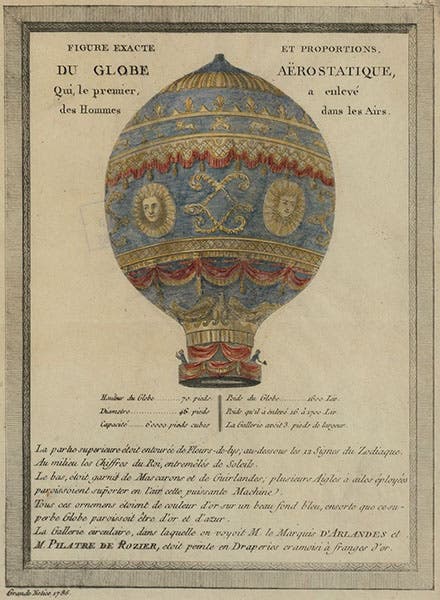

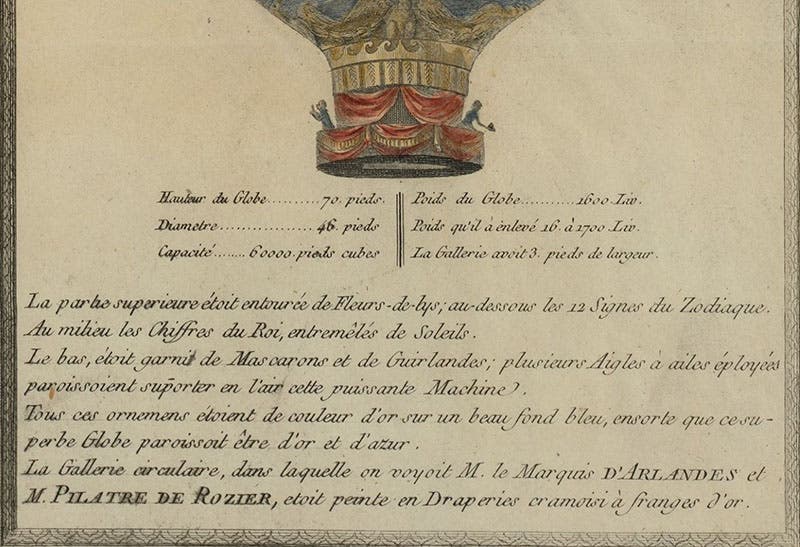

The Montgolfier brothers used a variety of balloons for these preliminary ascents, but they all had one thing in common – they were all hot-air balloons. Initially made of lacquered paper (they were paper manufacturers), and then of taffeta panels sewn together, the balloons had capacities approaching 60,000 cubic feet, which could hold enough hot air to lift a payload of 1500 pounds to an altitude of 3000 feet. Early balloons simply came down when the hot air cooled off, which was quickly. By the fall of 1783, the balloons had small braziers hanging beneath the open-bottomed gasbags, which burned straw fed to it by a passenger with a pitchfork, who had to be a very careful stoker.

On Nov. 21, 1783, there were 2 passengers: Pilâtre de Rozier, already introduced, and François d’Arlandes, a nobleman who was actually more than just a privileged hanger-on; he was even more competent than Pilâtre de Rozier, a professor of physics, and Arlandes later wrote the definitive account of their adventure.

As they were testing the balloon before liftoff, a gust of wind blew it over, and some of the seams popped. Arlandes asked for help from the crowd, and several women armed with sewing kits came forth and promptly re-hemmed the torn panels. The balloon was quickly reinflated, and just before 2:00, off she went, to the delight of the thousands of onlookers.

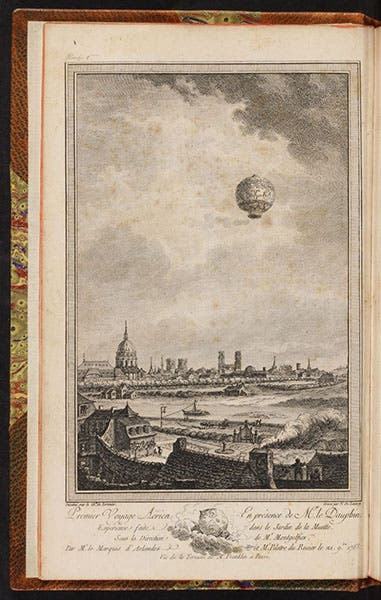

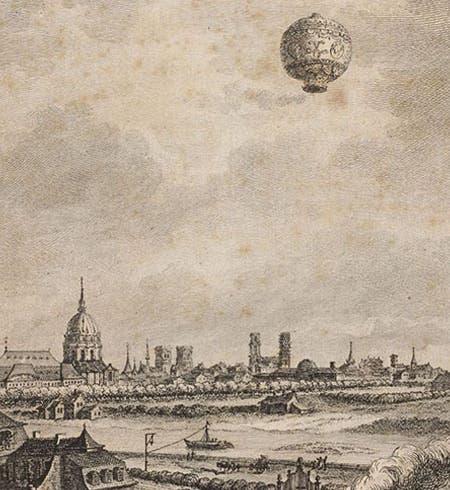

The balloon (which, interestingly, had no name) rose to about 3000 feet and moved along the Seine. One of the best viewing spots was Benjamin Franklin's terrace along the river, which is shown in our first image (and our sixth). Lots of artists sketched the balloon flight from there, but not Franklin himself, who was onsite at the launch. Franklin was supposedly asked by a skeptic, what was the use of a hot-air balloon, to which he famously answered, "what is the use of a new-born baby?"

Arlandes and Pilâtre were on opposite sides of the balloon platform and could only see each other, and communicate, via a small tube (fifth image). Arlandes was the fireman and was constantly adding straw to the fire pit. On one occasion, flying bits of straw ignited small patches of fabric on the balloon, which Arlandes was able to quench with a sponge stuck on the end of his pitchfork.

In all, they were aloft for only about 25 minutes, coming down between some windmills just outside Paris. The landing was gentle, and neither man was injured, although the collapsing balloon had to rescued from the still-burning embers, and Pilâtre as well, who was smothered in folds of the balloon fabric. The first free-ascending manned balloon flight was now history

First free ascent of a manned hot-air Montgolfier balloon, Nov. 21, 1783, with Pilâtre de Rozier and François d’Arlandes on board, engraved frontispiece, in Description des expériences de la machine aérostatique de MM. de Montgolfier, by Barthélemy Faujas-de-Saint-Fond, vol. 2, 1783-84 (Linda Hall Library)

As it turned out, the Montgolfiers scheduled their launch just in time, for not ten days later, on Dec. 1, 1783, Jacques Charles and a companion took off in a hydrogen-filled balloon, to become the second pair of aeronauts. The Aviation Age was off and running, or flying.

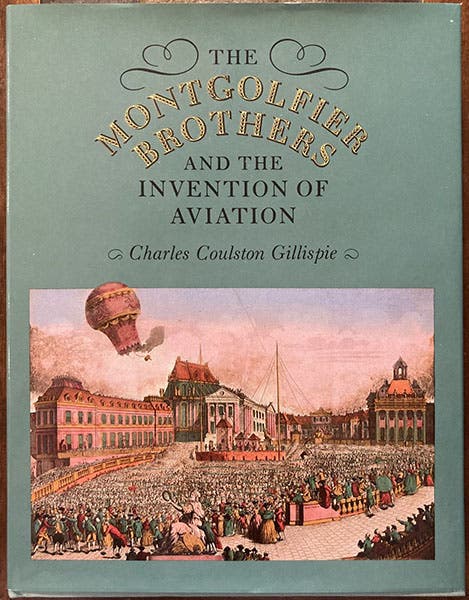

If you wish to read a single book on the beginning of the Age of Ballooning, I still recommend The Montgolfier Brothers and the Invention of Aviation, by Charles Coulston Gillespie (Princeton, 1983), a tall quarto brimming with original images and extracts from letters and documents of the period (last image). It is also witty and entertaining to read (I still recall Gillispie’s description of abbé Alexandre Montgolfier, one of several older brothers of Joseph and Étienne, who “had a career in the Church unmarked by devotion, success, or chagrin").

Dust jacket, The Montgolfier Brothers and the Invention of Aviation, by Charles Coulston Gillespie, Princeton Univ. Press, 1983 (author’s copy)

We have written about early balloonists many times in this series; see our posts on Faujas-de-Saint-Fond, d'Arlandes, Pilâtre de Rozier, and Charles. An early post on the Montgolfier brothers is in need of updating, but it does have several images I have not used elsewhere, including a photo of a bronze statue of the brothers in their hometown of Annonay.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Using an astrolabe to measure the depth of a well, woodcut in Elucidatio fabricae vsusq[ue] astrolabii, by Johannes Stöffler, 1513 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/a998eb50-55d2-4a88-ace2-a50aa5fa86e7/Stoffler%201.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)