Scientist of the Day - Thomas Ashe

Thomas Ashe, an Irish traveler and all-around scalawag, died Dec. 17, 1835, at the age of 65; his date of birth is unknown. In 1806, Ashe was in the United States, travelling through Pittsburgh, when he learned of a collection of fossil bones in storage there, the property of a Cincinnati physician, Dr. Goforth, who had collected them at Big Bone Lick along the Ohio River in Kentucky. Goforth was trying to sell his collection to the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia, which is why the bones were in Pittsburgh. Thomas Jefferson and Caspar Wistar were both quite interested in acquiring Goforth’s collection. When Ashe saw the giant bones, which included a mastodon skull with tusks intact, he hastened to Dr. Goforth and convinced him that he, Ashe, was the very broker he was looking for. Ashe crated the bones up and accompanied them downriver to New Orleans, where a generous offer of $7000 awaited him, but Ashe apparently decided that the profits to himself would be greater if he simply absconded with the fossils to England and cut Dr. Goforth out of the deal altogether.

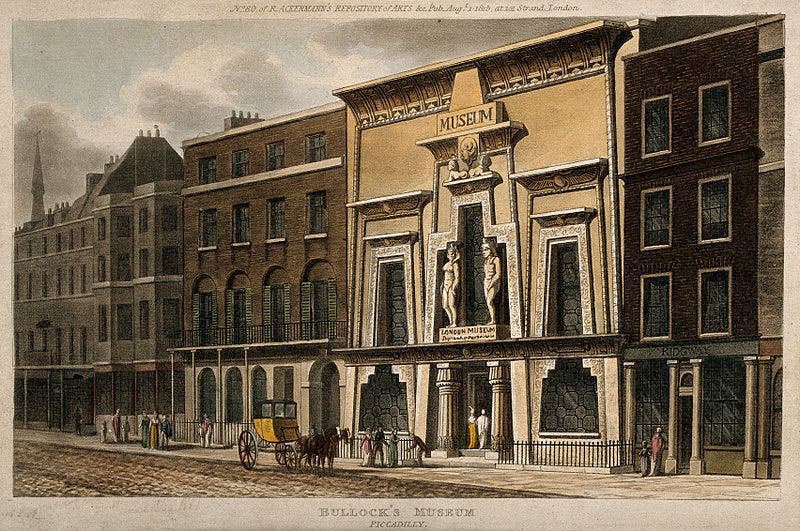

Unfortunately, when Ashe attempted to disembark in Liverpool, he ran afoul of the customs authorities, who would not allow the fossils off the ship without payment of a considerable tariff, and Ashe had to bailed out by a local entrepreneur, William Bullock, who offered a mere 200 pounds for the lot. Ashe had no choice but to accept, and Bullock added the 10 crates of bones to his already existing museum in Liverpool, which he would soon move to London (second image).

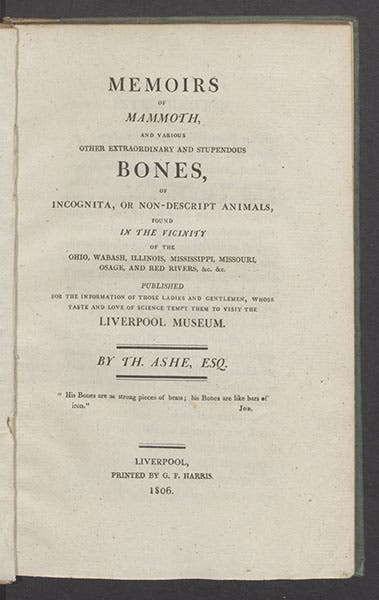

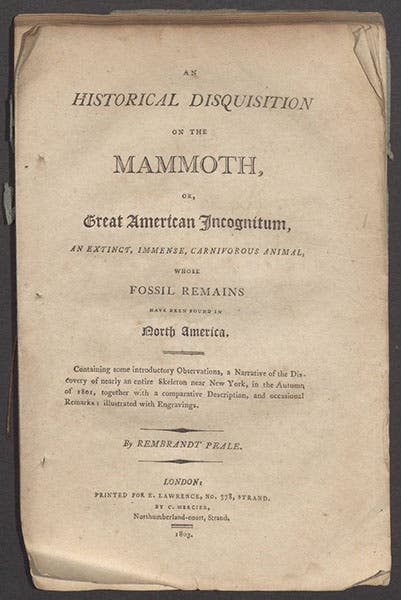

Still trying to cash in on his purloined fossils, Ashe wrote and published a short treatise, Memoirs of Mammoth, and various other extraordinary and stupendous bones, of incognita, or non-descript animals, found in the vicinity of the Ohio, Wabash, Illinois, Mississippi, Missouri, Osage, and Red rivers (1806; third image), in which he first described each of the crates of bones, and then provided an account of the terrifying by-gone days, when the American continent was under the sway of the formidable mammoth (which we would now call a mastodon) and the even more terrible Megalonyx, a clawed beast first discovered by Jefferson. The text was mostly plagiarized from the works of Jefferson and Rembrandt Peale, and we would ordinarily not elevate Ashe to the status of Scientist of the Day, were it not for the happy fact that we have a copy of Ashe's scarce pamphlet in our History of Science Collection, and not many libraries can make that statement. It sits in our vault right next to Rembrandt Peale's An historical disquisition on the Mammoth (1803; fourth image), and even fewer libraries can boast of having the pair.

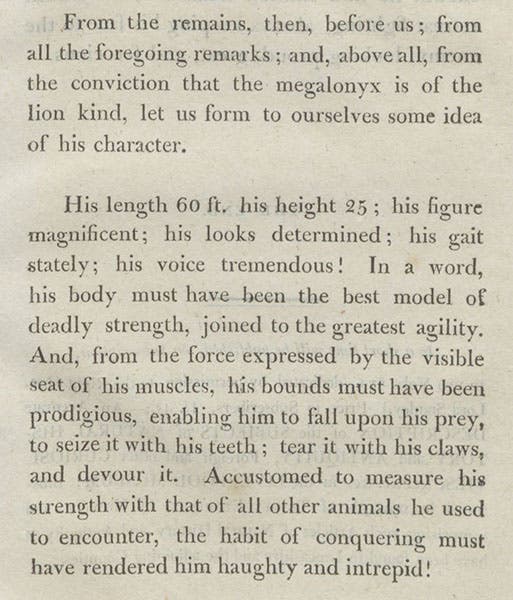

Ashe's book is unillustrated, but his verbal reconstruction of the Megalonyx can almost substitute for a picture (fifth image), especially when you compare it to his earlier description of the box containing the Megalonyx claws (first image). On reading both selections, you may also get some idea as to why Ashe was held in low repute by succeeding naturalists in both Britain and the United States.

Ashe later wrote a much longer book, Travels in America (1808), which has been described as an egregious collection of fabrications, and a memoir, Confessions of Captain Ashe... written by himself (1815), which reportedly is just as mendacious. It is unlikely that we will be adding either book to our collections in the future, but we are quite happy to have his Memoirs of Mammoth, the only place you are likely to find a description of a 60-foot long Megalonyx. Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.