Scientist of the Day - Thomas Bouch

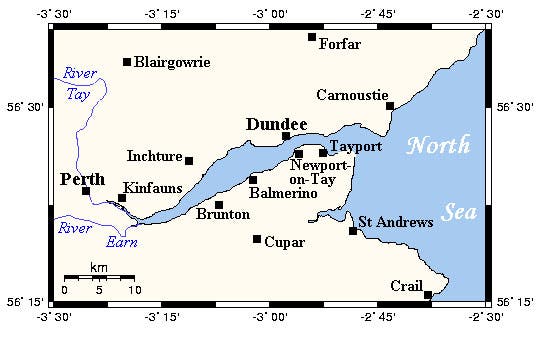

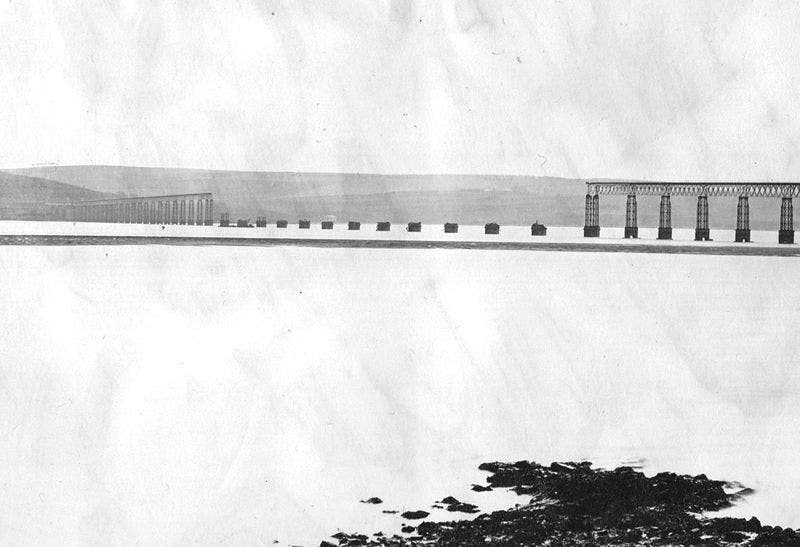

Thomas Bouch, a Scottish engineer who is often referred to as "poor Thomas Bouch," was born Feb. 25, 1822. Bouch was a civil engineer who designed railroads and bridges, and one of his designs, the Tay Bridge over the Firth of Tay in Scotland, opened for business on June 1, 1878. The bridge was quite impressive in its swing across the strait, as we see in our second image (the bridge is not really split-level, it just converts from a deck truss to a through truss in the center, to provide clearance for shipping lanes). The center section is often referred to as the “High Girders”. For those who are not firth-savy, our third image provides a map of the Firth of Tay - the bridge from Wormit on the south shore to Dundee on the north. Queen Victoria took the train across the firth in June, 1879, and she was so impressed she turned Mr. Bouch into Sir Thomas, almost on the spot. That, we surmise, was probably the high point of the life of poor Sir Thomas.

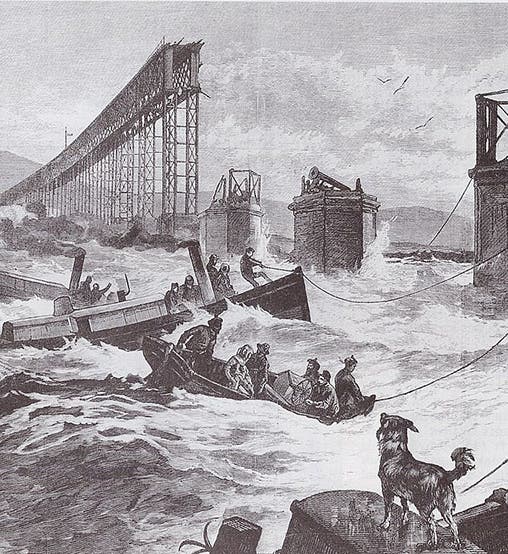

Barely five months after being knighted, Bouch’s world came tumbling down, along with his bridge. On Dec. 28, 1879, the high girders of the Tay bridge collapsed during an intense wind storm. As if that were not bad enough, there was a train on the central span at the time, which fell into the firth, and approximately 75 people died. It was the worst structural disaster in British history (and still is). Our first image shows a contemporary wood engraving of the scene immediately after the collapse, from the Illustrated London News.

The official enquiry revealed that the cast iron beams and girders were carelessly made, and that the design failed to properly accommodate the high winds in the area. Their conclusion was that the bridge was “badly designed, badly built, and badly maintained”, and they laid the blame directly at the feet of Sir Thomas. Bouch had just won the contract for the Firth of Forth Bridge, with construction scheduled to start the next year, and that was pulled and awarded to another firm (whose bridge still stands). As if the shame was too much to bear, Bouch died less than a year later. A replacement bridge was begun immediately and opened in 1887; it is still standing and in regular use.

The collapse of the Tay Bridge has been subject of intense debate among bridge engineers ever since. Everyone seems to agree that Bouch should have allowed for wind-loading in his design (he had not), and he did oversee construction and maintenance. But many argue that the Wormit foundry that produced the cast iron beams and trusses deserves much of the blame, since many of the castings were faulty, and imperfections were covered up with the metallic equivalent of wood putty.� Others point out that the wind speeds that night, up to 80 mph, were unprecedented in the area and such high wind-loading could not reasonably have been expected.

But in the end, it was Thomas Bouch’s disaster and probably forever will be. An art dealer has been offering for some time a splendid contemporary portrait of Bouch (fifth image). So far, no one seems to have been interested. Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.