Scientist of the Day - Thomas Chrowder Chamberlin

Thomas Chrowder Chamberlin, an American geologist usually referred to as T.C. Chamberlin, died Nov. 15, 1928, at age 85. In Chamberlin's day, most astronomers subscribed to what is called "the nebular hypothesis", which proposed that the solar system condensed from a massive cloud of gas and dust. Although Chamberlin was a geologist, working on ice ages and climate change, he liked to think of himself as a “telluric” astronomer, and he had his doubts about the nebular hypothesis. Working with a young astronomer, Forest Moulton, he suggested that the planets were built up from small particles, called planetesimals, by a process of accretion. He thought this would explain why the Earth held on to the light gases in its atmosphere, which would have escaped if the Earth had once been hot or molten.

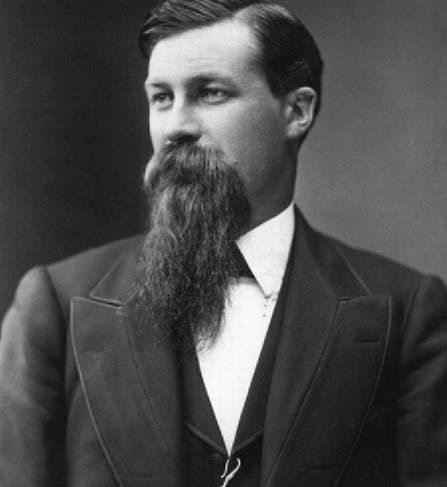

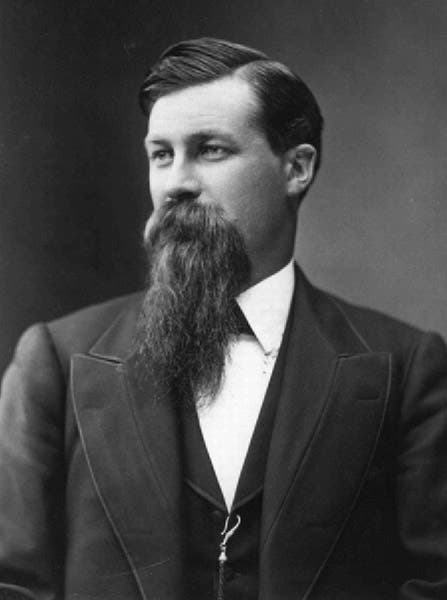

Portrait of an older T.C. Chamberlin, photograph, 1890s, Popular Science Monthly, 1897, vol. 51 (Linda Hall Library)

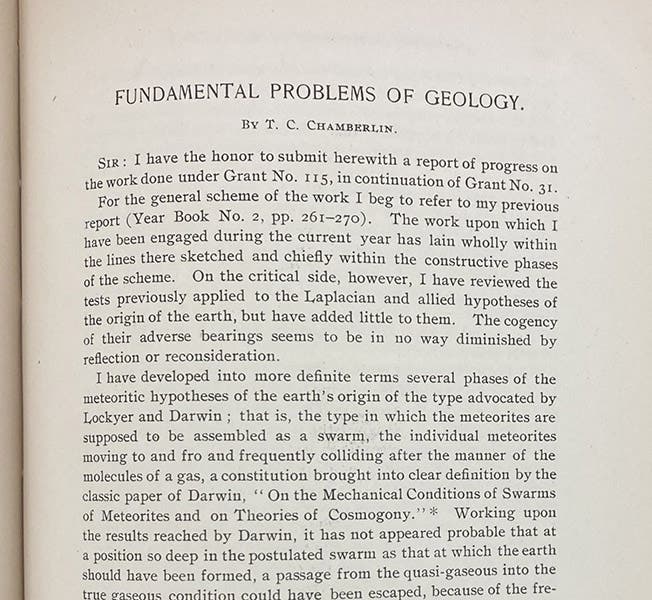

The Chamberlin-Moulton planetesimal hypothesis, sometimes called the “meteoric hypothesis,” was first proposed in 1901; in 1904, Chamberlin fleshed it out with the idea that the material of the planets might have been the result of an encounter with a passing star, which pulled out material from both stars to form first the planetesimals, and then the planets. We show here the first page of Chamberlin’s 1904 article in the Yearbook of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, in which the star-encounter hypothesis first appeared. The “Darwin” referred to is not Charles, but his son George Darwin, a prominent geologist.

First page of paper by T.C. Chamberlin, proposing that a star once passed close to the sun and drew out material from both stars, which formed first into planetesimals, and then the planets, Yearbook, Carnegie Institution of Washington, no. 3, 1904 (Linda Hall Library)

The Chamberlin-Moulton encounter hypothesis was the dominant theory of planetary formation for the first half of the 20th century. It also implied that the existence of planets is an unusual cosmic situation, since encounters between stars should be quite rare. The Chamberlin-Moulton hypothesis fell from favor in the 1940s, when it developed mechanical problems, and the nebular hypothesis, with some repairs, was restored to respectability, and with it the corollary that planetary systems should be quite common in the universe, which has now been confirmed.

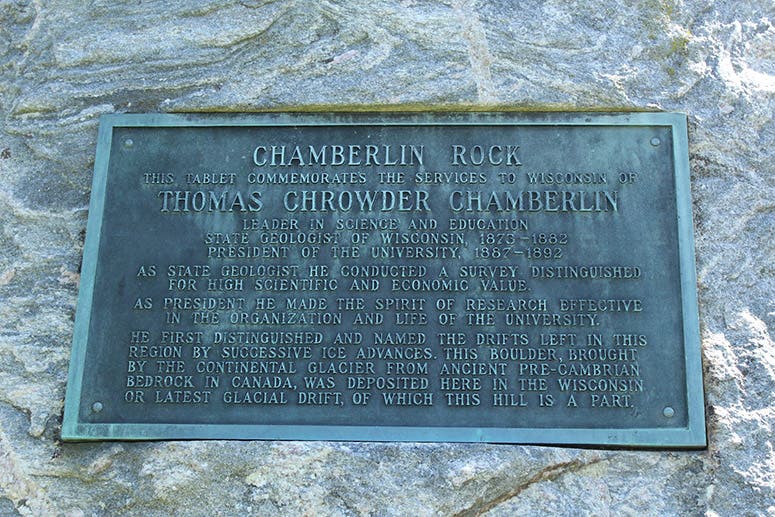

Chamberlin also made a mark with more traditional geological activities, mapping glacial deposits in Wisconsin (he named the four different Wisconsin glaciations), heading up the Wisconsin State Geological Survey, and even serving for a period as President of the University of Wisconsin in Madison, before he headed off to the University of Chicago and his work on solar system formation. Until recently, there was a large glacial erratic boulder that sat alongside Observatory Drive on the UW-Madison campus, near Washburn Observatory. After Chamberlin’s death in 1928, the erratic was named Chamberlin Rock, and a plaque was installed commemorating Chamberlin. Unfortunately for Chamberlin, a campus activist group discovered that the rock, before it became Chamberlin Rock, had once been referred to by a racial epithet. They lobbied for the rock’s removal, and even though the rock was mute and had said nothing, the administration sided with the protestors, and the rock was carted away in 2021 to some university land south of Madison, presumably a less offensive location. The rock was accustomed to travelling, being some 2 billion years old, and having come down to Madison from Canada during a recent glaciation. This was its first peregrination by truck. The plaque was removed before the rock was banished; I do not know where it ended up.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.