Scientist of the Day - Thomas Dimsdale

Untitled caricature by Isaac Cruikshank, hand-colored etching, 1808, lampooning three anti-vaccination surgeons and praising “Edward Jenner and two colleagues,” traditionally considered to be Thomas Dimsdale and George Rose, although none of these are identified in the caricature itself; Wellcome Collection (wellcomecollecton.org)

Thomas Dimsdale, an English physician, died Dec. 30, 1800, just two days shy of the advent of a new century. He was 88 years old. In 1767, Dimsdale published a book, The Present Method of Inoculating for the Smallpox, which proved to be very popular, going through many editions in just a few years. Inoculation against smallpox was a procedure that was at least 50 years old in England at the time of Dimsdale's book, and had been used since the 17th century in other countries. It consisted of injecting, into a skin incision in a healthy person. a small amount of material from a pustule of a person stricken with smallpox. The term inoculation thus meant something different from the modern term, and for this reason, historians of medicine often use the term variolation to denote the injection of live infectious material, but we will stick with the word inoculation here, as it was the term in use in Dimsdale’s lifetime.

In 1768, Dimsdale was invited by Catherine II, Empress of Russia, to come to St. Petersburg to inoculate her against smallpox. It is not clear why Dimsdale was chosen, since he was far from the most famous inoculator; the appearance of his book, and his upper-class status, seem to have been the deciding factors. That Catherine should have chosen an English physician seems odd, since she was much more partial to the French than the English, and was at the time engaged in a long correspondence with Voltaire, but French physicians, especially the faculty of the school of medicine at the Sorbonne, were adamantly against inoculation, and Catherine grew disgusted at their recalcitrance and reached across the channel for assistance.

Dimsdale accepted the invitation and made his way to Russia, and Catherine was inoculated on Oct. 12, 1768. As was typical with inoculation, she came down with mild symptoms of smallpox and was miserable for a day or two. But within two weeks, she was back to her bouncy self, and so Dimsdale proceeded to inoculate her son, and then most of the members of the court nobility and their families, some 140 in all. Everyone survived, which was unusual, as typically, inoculation had a 1-2% mortality rate. Dimsdale was lionized by Russian society and was given a lump sum payment of £10,000 and a lifetime annuity and was made a Baron of the Russian Empire. Catherine was lionized as well, for having the guts to defy the academic physicians and be the first one to be inoculated. Most important, in the long run, was that Russia took a giant step in westernization, a process that had begun with Peter the Great but which had made no great strides until Catherine’s decision to use western medical methods to improve the lives of herself and her people.

In 1796, Edward Jenner, an English surgeon, developed a similar procedure to Dimsdale’s inoculation, except that Jenner used live material from a victim of cowpox instead of smallpox. This process Jenner called vaccination, after vacca, the Latin word for cow, and it came to be the preferred procedure, since there was less risk of coming down with smallpox. In practice, the terms inoculation and vaccination were used interchangeably until later in the 19th century. When Isaac Cruikshank, in 1808, chose to lampoon anti-vaccination physicians in a caricature, his good guys, the “Preservers of the Human Race” standing on the right, were Jenner, Dimsdale (presumably the one with the white hair), and George Rose, who founded the National Vaccine Establishment in 1808. When this print was published, Dimsdale had been dead for 8 years, but his contribution to the success of vaccination was clearly still remembered and respected.

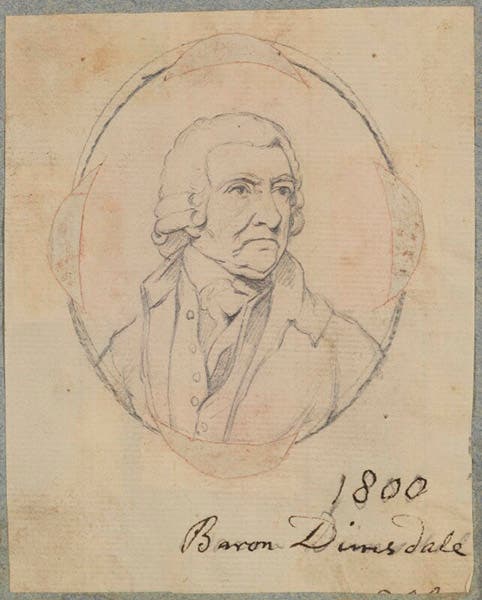

The pencil sketch of Dimsdale, by Henry Bone, was made in the year of his death and is in the National Portrait Gallery in London (second image). The Cruikshank caricature is in the Wellcome Collection in London (first image). The portrait of Catherine the Great is in the Yekaterinburg Museum of Fine Arts in Russia (third image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.