Scientist of the Day - Thomas Hancock

Thomas Hancock, an English inventor and manufacturer, was born May 8, 1786, in Marlborough, Wiltshire. He is to the rubber industry in England what Charles Goodyear is to the United States. Hancock worked as a coachmaker for some years, and it was apparently while so employed that he began to experiment with rubberized fabrics. He had been anticipated here by Charles Macintosh, a Glasgow inventor who, by 1824, had patented a way of dissolving rubber in naptha and painting it onto fabric, producing a weatherproof cloth that found all sorts of uses.

Hancock, at first unaware of Macintosh, invented a machine to recycle rubber remnants, essentially by chewing them up in a machine with rotating teeth. He called his machine a "pickle," apparently a ruse to make rivals think there were chemicals involved in the process. Later, it would be called, more descriptively, a "masticator." And, as it turned up, masticated rubber made better rubber products than rubber straight from the tree, because it was moldable. By 1830, Hancock and Macintosh had teamed up, Hancock producing the base rubber that Macintosh dissolved and turned into waterproof coats and boats. They maintained their separate plants in Glasgow and London.

Sometime before 1843, Hancock discovered how to vulcanize rubber with sulfur. This was an important advance in rubber products manufacture, because unvulcanized rubber is very susceptible to acids and can lose elasticity long after manufacture. Vulcanization produced a rubber product that was stable for a much longer period of time than unvulcanized rubber. How Hancock discovered vulcanization is a contentious subject. Charles Goodyear had already discovered vulcanization in the United States, but he had failed to arouse any interest among manufacturers. Apparently, he sent samples to England to stir up interest there, and it is said that several of these samples came to the attention of Hancock. Some historians, those in Goodyear's camp, maintain that Hancock was able to "reverse engineer" the vulcanization process from Goodyear's samples. Others maintain that that was impossible, given the state of industrial chemistry in 1840. Perhaps Hancock merely smelled sulfur in the samples and went from there. What is certain is that he patented his vulcanization process in England in 1843, several months before Goodyear received his patent in the United States, which meant that Goodyear could not secure a British patent. When Goodyear later challenged Hancock's patent in British courts, he lost, unable to sustain the charge that Hancock had stolen a process invented by Goodyear.

Vulcanized rubber made a big splash at the Crystal Palace Exhibition in London in 1851; Hancock and Macintosh each had a stand, where they displayed all sorts of rubber products, vulcanized and unvulcanized. Goodyear had a booth as well, with an equal variety of rubberized products. We have a four-volume Official Descriptive and Illustrated Catalogue of the Great Exhibition (1851) in our history of science collection, where we find that Hancock displayed at booth 83 in Class 28 (manufactures from animal and vegetable substances), and Macintosh at nearby stand 76. The entry on Hancock in volume 2 is only a couple of lines, but the entry on Macintosh fills almost two columns, and most of the space is devoted to extoling Hancock and his invention of the vulcanization process. I could find no images of any of the goods displayed by Hancock or Macintosh in the Catalogue. However, the Science Museum in London has a vulcanized “India rubber plaque” that was exhibited in 1851, which has the names of both Macintosh and Hancock as patentees; we showed it in our post on Macintosh. And in 2020, Sotheby's offered at auction a medallion portrait of Hancock, made of vulcanized rubber, that was also exhibited at the Great Exhibition. We don’t know who bought it, but we can show you the photograph from the Sotheby catalogue (first image).

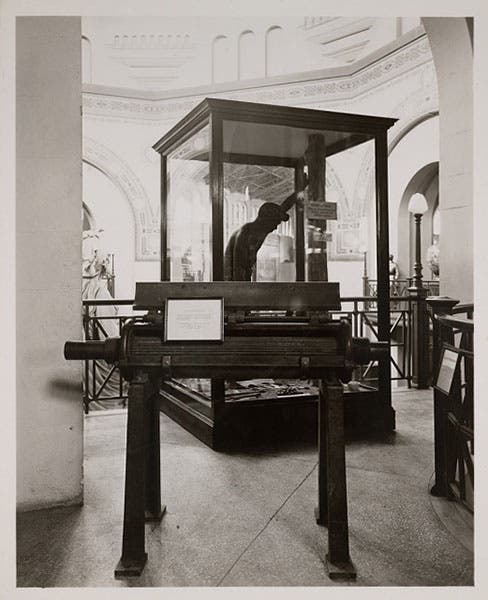

You would think there would be plenty of Hancock masticators on display in museums of science and industry, but if they exist, they are hard to locate. The Science Museum in London has only a few simple vulcanizing lamps made by or for Hancock, and no masticator. I did manage to find an old photograph that showed a Hancock masticator on display in the Smithsonian Institution around 1920 (third image; the masticator, not easy to make out, is in the foreground, with a label that identifies it). But the masticator was long ago removed from display and is now in storage somewhere in the National Museum of American History (fourth image).

Hancock did publish a book on his involvement in the development of the rubber industry in Great Britain, called Personal Narrative of the Origin and Progress of the Caoutchouc or India-Rubber Manufacture in England (1857). But we do not have it in our collections. It is abundantly illustrated with cutaways of masticators and other machines, and it also includes the portrait that is usually used in articles on Hancock (second image). You can see three thumbnails of images from this book on this Destination London webpage. We will try to acquire a copy of Hancock’s book.

Hancock died Mar. 26, 1865, at age 78, and was buried under a memorial column in Kensal Green Cemetery in London, where he shared the earth with Marc Isambard and Isambard Kingdom Brunel, and would soon be joined by Charles Wheatstone and Charles Babbage. But a golden opportunity to mold a monument in vulcanized rubber was lost.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.