Scientist of the Day - Thomas Henry Huxley

Thomas Henry Huxley, an English comparative anatomist, was born May 4, 1825. By 1870, Huxley was one of the best and best-known natural scientists in England – an early and eloquent defender of Darwinian evolution, an outspoken opponent of England’s other skilled anatomist, Richard Owen, and the author of a popular book, Man’s Place in Nature (1863), which we discussed in an earlier post on Huxley.

Thirty years earlier, in 1840, Huxley was trying to fight his way out of poverty. His father lost his teaching job, and Thomas had to be pulled from school and apprenticed to a variety of surgeons. He was determined to pull himself out of the mire, and he embarked on a program of self-education, reading everything he could lay his hands on. He managed to do well on exams and got through a year at the University of London before running out of funds, at which point he joined the Royal Navy as a prospective ship’s surgeon. He had a well-defined goal: go to some part of the world where most English naturalists had never been; carve out an area of study he could call his own; and write paper after paper to send back to the Linnean Society and perhaps the Royal Society of London. He would enter the field of natural history through the back door.

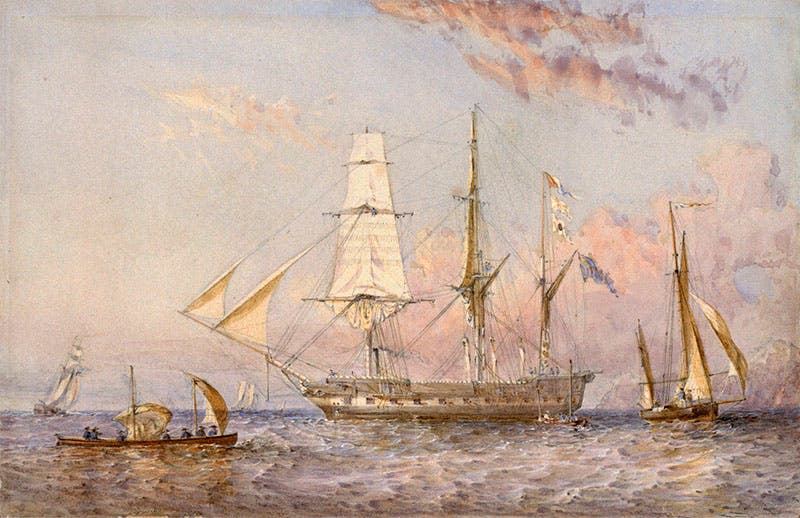

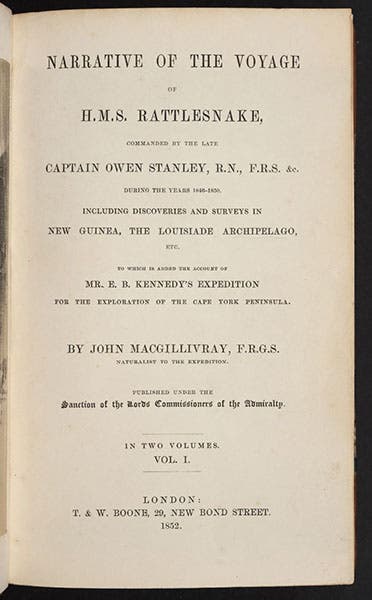

The area of study he chose was invertebrate zoology, the study of jellyfish and sea squirts and tunicates, which French naturalists had written about a great deal, but which had attracted few English partisans except Edward Forbes and Robert Grant (and soon, Charles Darwin). Huxley was appointed assistant surgeon on HMS Rattlesnake (third image), which was being sent to explore the Torres strait north of Australia, and the Louisiade Archipelago at the eastern end of Papua New Guinea. He knew that Darwin had gotten his start this way, and Huxley hoped to follow in his wake, quite literally.

The voyage of the Rattlesnake, 1846-50, was generally a disaster. The ship was in terrible shape, and so, by the end, was the captain, Owen Stanley. Stanley became overly cautious, afraid of the native Papuans, seldom landing on any of the islands they visited, and when they did, refusing to allow his men to explore further than the beach. The area was blistering hot, infested with all manner of insects, and treacherous to navigate, with an abundance of reefs (which the Rattlesnake was sent to map). Many men died, and the rest were miserable. Yet somehow, Huxley found a way to work, dredging up sea life (as Forbes had taught him), dissecting Portuguese men o’ war and other soft-bodied sea creatures and studying them with his microscope, which he had to bolt to a table in the rough seas. He wrote papers, demonstrating that the French were often wrong in their details about marine invertebrates, and sent them back to be published in English journals. He even managed to find the love of his life in Sydney, his future wife Henrietta, although she would not be able to join Huxley in England for a long time.

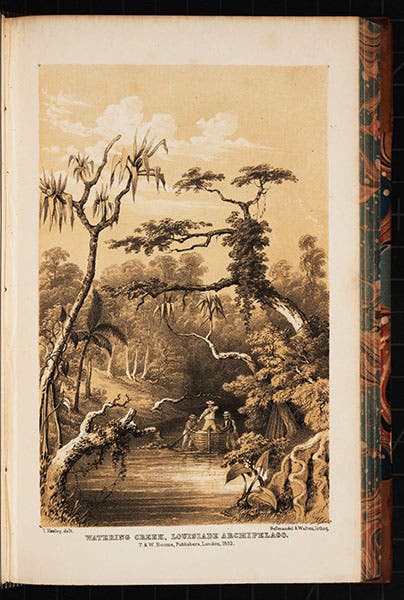

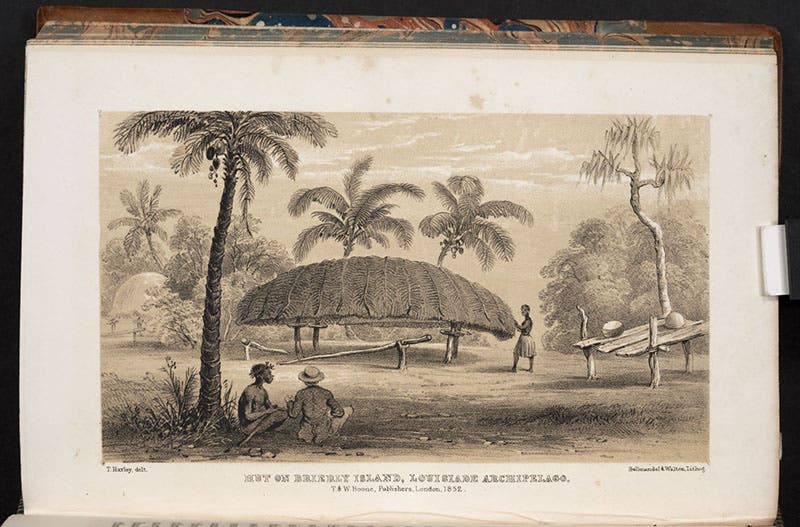

“Hut of Brierly Island, Louisiade Archipelago,” tinted lithograph after drawing by Thomas H. Huxley, in Narrative of the Voyage of H.M.S. Rattlesnake, by John MacGillivray, vol. 1, 1852; Oswald Brierly, after whom the island was named, was the landscape artist on board HMS Rattlesnake and did the watercolor of the ship that we show as our third image (Linda Hall Library)

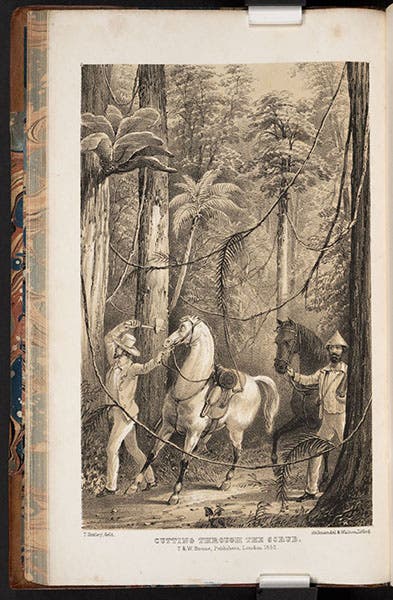

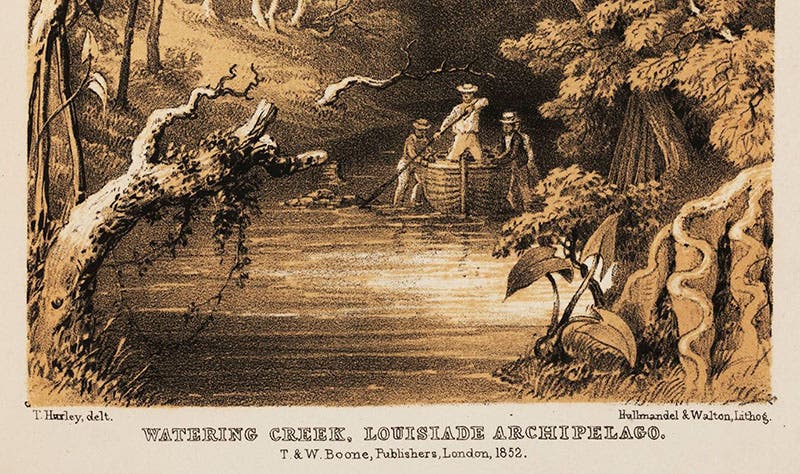

Captain Stanley had rapidly gone downhill, health wise, as the voyage progressed, and he died in 1850, before the Rattlesnake left Sydney to return to England. The Narrative of the Voyage was written by John MacGillivray, who was the official naturalist on the Rattlesnake, and with whom Huxley became a close friend and colleague. The book is illustrated with tinted lithographs, and many of them are based on drawings by Huxley, who taught himself to be a more-than-competent sketch artist. We show three of those here, all depicting activities of the crew in the Louisiade Archipelago. Huxley is shown in several of them; he wields the hatchet in the fourth image. The sixth is a detail of the first, so you can see the signature at the left, “T. Huxley delt” – “Thomas Huxley drew this.”

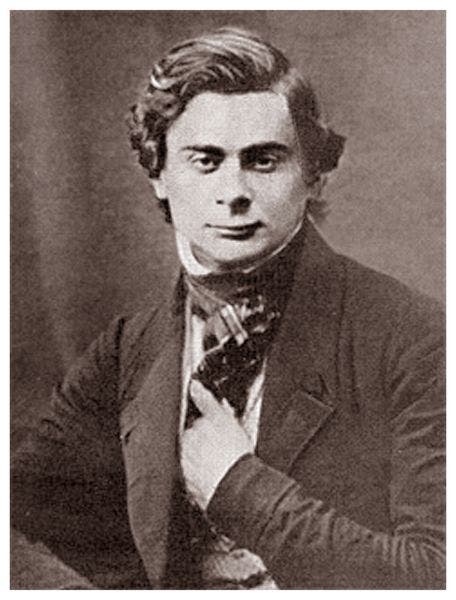

Fortunately, Huxley’s work and foresight paid off. After his return to England, he rapidly rose through the ranks of British naturalists, was appointed professor of anatomy at the Royal School of Mines in 1854, was able to bring his fiancée Henrietta to England in 1855 and raise a family, and soon was being accorded the same scholarly respect as Darwin, Owen, Forbes (who died in 1854), and John Dalton Hooker, the botanist. A portrait made ten years after our first portrait (last image) still lacks some of the air of confidence that we see in the many photographs taken in the 1860s and later. But he is getting there. Once again, a voyage around the world had been the proving grounds for a determined young naturalist.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.