Scientist of the Day - Thomas Savery

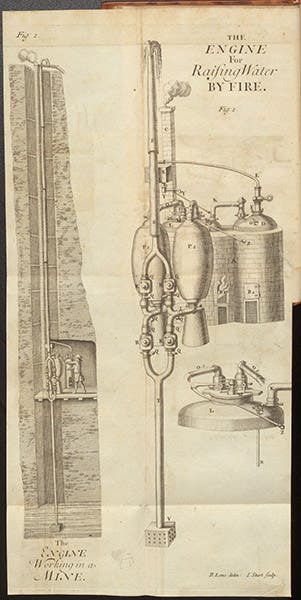

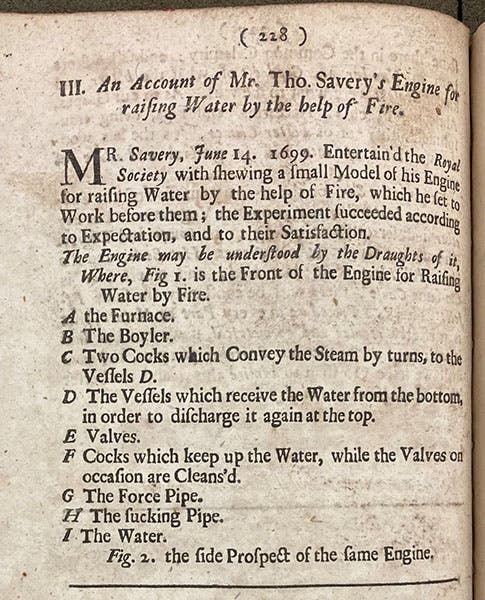

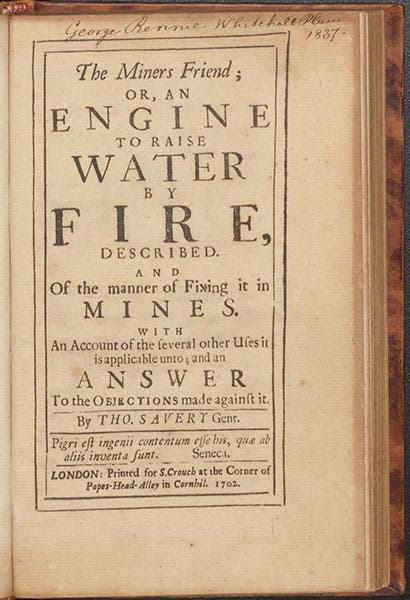

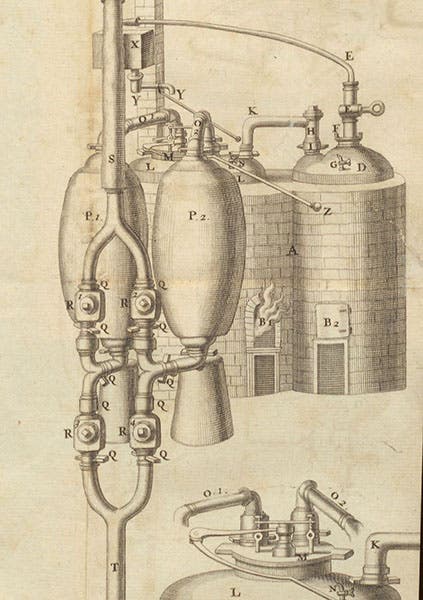

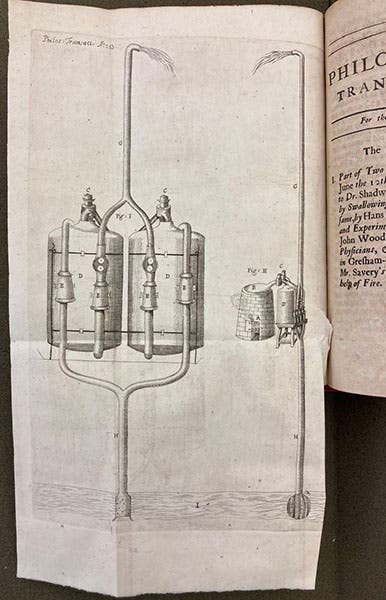

Thomas Savery was an English military engineer with a fondness for invention. On this date, June 14, 1699, he demonstrated his latest invention to the assembled fellows of the Royal Society of London. It was a steam-powered pump, for which he had received a patent the previous July, the first patent ever for a steam-powered "device." A one-page summary of his demonstration was published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Society (third image), along with a plate illustrating his model (eighth image). Three years later, Savery published his own account of his pump, a book with the title: The Miner's Friend, or an Engine to raise Water by Fire (third image), which included a large fold-out engraving of his steam pump, this time full size (first image). We will use this engraving, and several details, to explain how the pump worked. It is often called a steam engine, and while strictly speaking it is not an engine, since it produces no torque, there is really nothing wrong with referring to Savery’s “Miner’s Friend” as a steam engine, although I have tried not to do so.

Savery’s device used a boiler to produce steam, which was conveyed by pipes to two closed vessels, set up in parallel. These vessels were connected via shut-off valves (stopcocks) to a downpipe, and also to an up-pipe, which you can see in the full engraving (first image). When one of the vessels was filled with steam, it would be closed off by the stopcocks and then cold water would be poured on it. This caused the steam to condense, producing a vacuum in the vessel. When the valve to the downpipe was opened, water would be drawn up by the vacuum to fill the vessel, at which point the downpipe stopcock would be closed and the up-pipe stopcock opened. When steam was now introduced again into the vessel, the water was pushed up the up-pipe by steam pressure.

Meanwhile, the other vessel went through the same cycle, but alternating with the first, so that while one vessel was filling with steam, the other was filling with water. It was an ingenious design. It could pull water up about 20 feet (the theoretical limit is 32 feet), and then pump it up another 30 feet or so. To pump it any higher would require more steam pressure than the joints in the pipes or the seams in the boiler could bear.

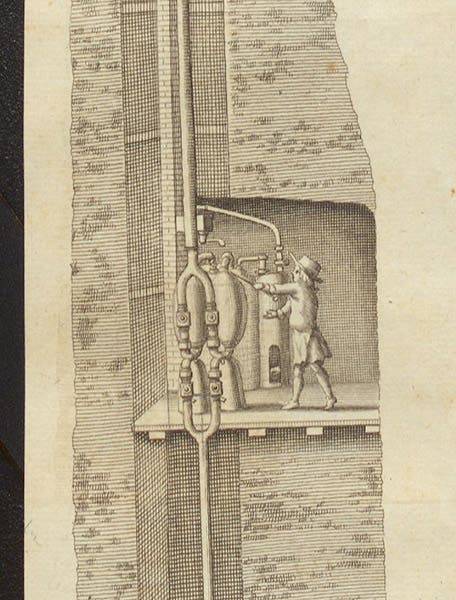

Savery’s pump was actually put into operation in several mines. But because the downpipe was only 20 feet long, the pump and boiler had to be placed underground, down in the mine, and even then it could only raise water another 30 feet. Most mines were far deeper, which would require a series of pumps. In addition, Savery’s steam pump was dangerous, since it operated at high pressure. When Thomas Newcomen, 10 years later, invented his atmospheric steam engine, which operated at low pressure, it was immediately preferred by mine operators, even though it was terribly inefficient, because it would never explode. This did not bother Savery too much, since his patent of 1698 covered all devices for raising water, and thus Newcomen had to take Savery into partnership to avoid violating the terms of the patent.

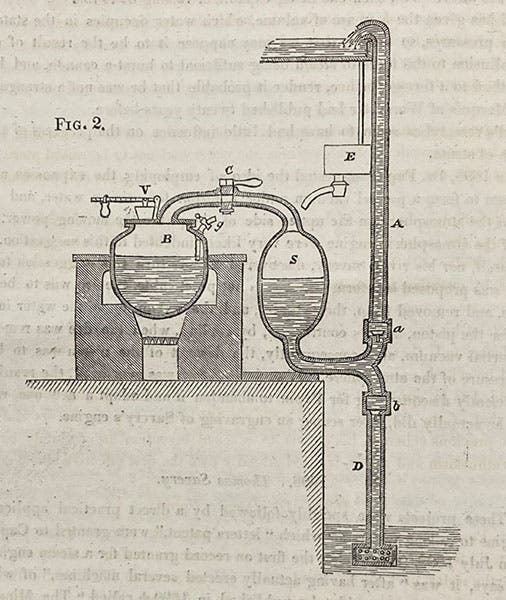

In 1827, Thomas Tredgold published a history of the steam engine, and he included a plate of Savery’s pump that was simplified from Savery’s own diagram, and a little easier to understand, so I have included it here (seventh image). Bear in mind that part of the simplification consisted of showing only one of the vacuum vessels, instead of the pair.

If you search for a portrait of Thomas Savery on Google Image, you will find scores of examples based on one single image, but amazingly, and really unforgivably, not a single website identifies the original source, so I do not use it here. The supposed portrait appears similar in style to the portraits that one finds in Louis Figuier’s Les merveilles de la science (1667-91), but it is not in there, unless I missed it, and I looked. Figuier does however provide a wood engraving of Savery doing a demonstration in a tavern, so I include that instead, even though it is not a valid portrait either. At least I know where it comes from.

We displayed Savery’s Miner’s Friend in an exhibition in 2008, called Locomotion: Railroads in the Early Age of Steam, curated by our former rare book librarian, Bruce Bradley. The very attractive brochure is available online; the plate from Savery is on page 4.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.