Scientist of the Day - Thomas Wollaston

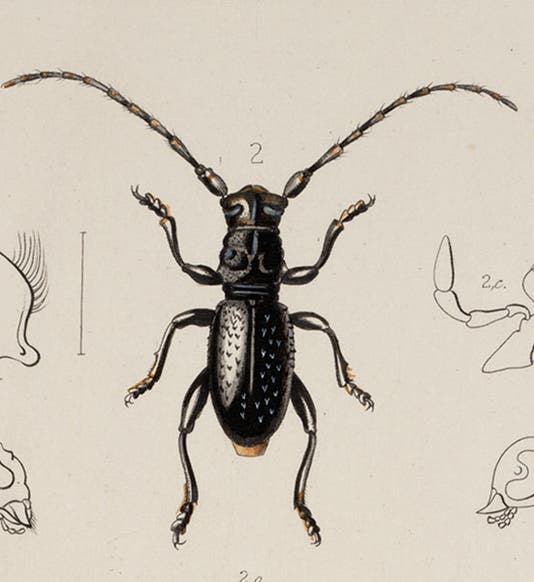

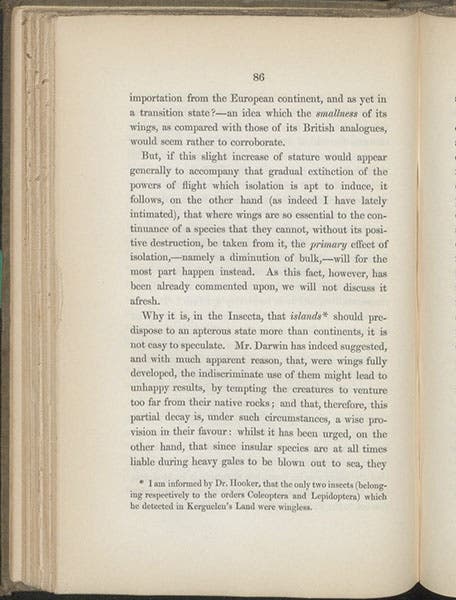

Thomas Vernon Wollaston, an English entomologist, was born Mar. 9, 1822. Wollaston, like his older contemporary Charles Darwin, took to collecting insects at an early age, but unlike Darwin, he never really enlarged his horizons. He made four trips to Madeira, the Atlantic archipelago about 300 miles southwest of Portugual, while he was still in his twenties, and in 1854, he published Insecta Maderensia, a large two-volume quarto with more than most would ever want to know about the insects of this island group. He was especially interested in beetles, and he noticed that any species of beetle that could fly were found on all the islands, but those that were "apterous" (flightless) were often confined to a single island, and in the case of some, to a single mountain top on a single island, and nowhere else in the world. Wollaston illustrated many beetles in his book, with attractive hand-colored engraved plates. We show one plate (third image), and a detail of that plate (first image), the Deucalion beetle, which is found on only one tiny island in the Salvage Island group, some ways south of the Madeira archipelago.

Wollaston also had some ideas that species might have high degree of variability, and that observation, plus his Madeira beetles, attracted him to Charles Darwin. In 1856, when Darwin had just started his "Big Book," the predecessor to the Origin of Species, Wollaston was invited to Down House, along with Thomas Henry Huxley and Joseph Dalton Hooker, and apparently they had quite a discussion about species variability, with some suggesting that species could vary without limits. Word of the unorthodox gathering traveled through the wider circle around Darwin, with Charles Lyell commenting on it in his letters.

Wollaston that same year published his own book, On the Variation of Species, With Especial Reference to the Insecta (1856; fourth image). In several passages, he praised Darwin highly, as when he discussed the insects of Tierra del Fuego collected by Darwin. We show two pages that mention Darwin here (fifth and sixth images). But near the end of his book, Wollaston discussed transmutation, the generation of new species from old ones, and here it becomes clear that he and Darwin were not on the same page. Like most other naturalists who discussed transmutation, he felt there were very definite limits as to how much species could vary, and he was far from embracing transmutation into new species.

Wollaston wrote a letter to Darwin the next year (1857), and it seems he still held Darwin in high esteem, as he wrote: “There are not, alas, many Darwins in the world; & there is not (certainly) one single entomological D in all Beetledom,” which I find rather charming, or perhaps I just like the term "Beetledom." But that was about it for Wollaston-Darwin interactions. Darwin mentioned the Madeira beetles several times in the Origin of Species, to show the importance of isolation in forming new species, but when he espoused transmutation (evolution) by natural selection, with no limits, he left Wollaston far behind. All of the later mentions of Wollaston in Darwin's correspondence relate to Wollaston's bankruptcy and flight from his creditors around 1866. Apparently Wollaston fled to other Atlantic Islands, for he would later publish a book about the beetles of the Azores, Canaries, and Cape Verde islands. He died in 1878.

There is only one good photograph of Wollaston, and it has been cornered by one of those photographic agencies that I so dislike, which collect public-domain images and then plaster them with watermarks that can only be removed by paying a fee. At this link, you can see the photo portrait of Wollaston, plus the watermarks, since I refuse to pay a fee for an image in the public domain.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.