Scientist of the Day - Thomas Young

Thomas Young, an English polymath, was born June 13, 1773. There are only 7 individuals in my catalog of scientists for whom I have included the keyword "polymath" (the others being Aristotle, Leonardo da Vinci, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and Alexander von Humboldt), and, on any polymathy scale, Young would have to rank at the very top. Young is best known for establishing the wave theory of light and demonstrating it with a now famous experiment known as the double-slit experiment (which we will discuss below). But Young also made the first real progress in deciphering the Rosetta stone (making possible, so Young argued, Champollion's success in 1822); he showed how the eye’s focusing mechanism works and discovered astigmatism; he proposed the three-color theory of vision for receptors in the eye (now established as correct); he was a gifted linguist who introduced the term "Indo-European" to describe the language family that includes the Anglo-Germanic and Romance languages. He was also principal physician at a London hospital for 25 years and had an extensive private practice

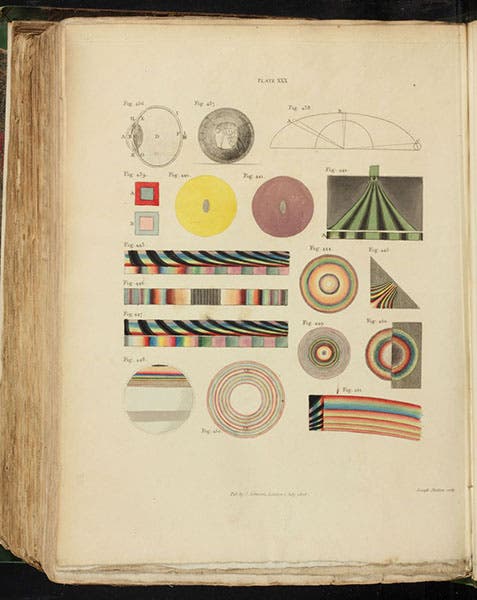

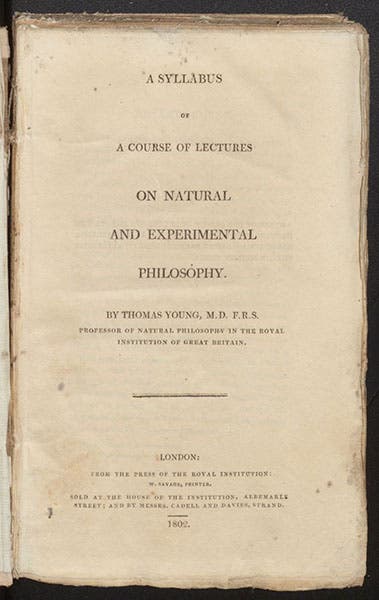

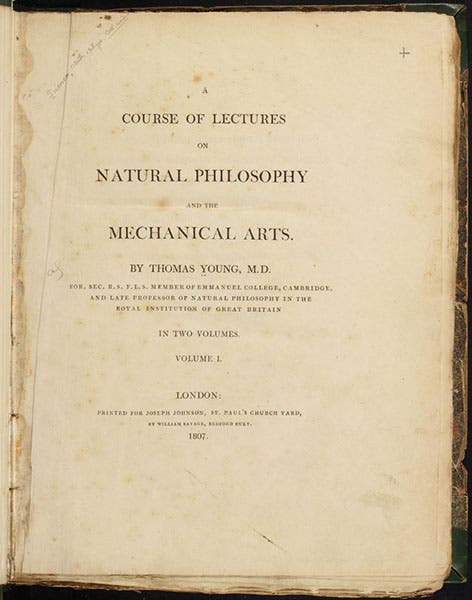

In 1801-02, Young gave a series of lectures at the newly-founded Royal Institution in London on every branch of science you can imagine, including mechanics, optics, electricity, magnetism, hydraulics, astronomy, and even natural history. We have the printed syllabus for this course in the Library (third image) – it is nearly 200 pages long (my typical course syllabus was about 4 pages)! The lectures were eventually published in 1807, in two fat quarto volumes, as A Course of Lectures on Natural Philosophy and the Mechanical Arts – we have this set in our History of Science Collection as well, and have included several plates from it here. Young inserted into volume 2 an annotated bibliography of suggested reading that stretches for 440 pages! I doubt if ever before, or since, any one human has given such a wide-ranging series of lectures, and with such expertise.

The famous double-slit experiment merits special attention. In Young's day, most English physicists still followed the lead of Isaac Newton, who considered light to be particulate, or corpuscular. Young, however, adhered to the wave theory of Christian Huygens and Robert Hooke, but he wasn't having much luck convincing the opposition. Then he devised the double-slit experiment, and that would turn the tide. Young showed that if you allowed light to pass through two slits that were a small distance apart, the waves would interfere with one another and produce a series of bright and dark vertical lines on a screen placed in their path – what we now call an interference pattern. If you covered one slit, the light-and-dark lines disappeared. The corpuscular theory was unable to predict or account for such interference patterns. It is not clear, incidentally, that Young ever performed the double-slit experiment, but the results, if one does do it, are exactly what he stated.

Young described the double-slit experiment in his Bakerian lecture before the Royal Society in November of 1803, then included it at the end of volume 2 of his Course of Lectures. In 2003 (coincidently on the 200th anniversary of the experiment), a philosopher of science, Robert Crease, published a book called: The Prism and the Pendulum: The Ten Most Beautiful Experiments in Science. Young's double-slit experiment was included among the ten, along with Eratosthenes’ measurement of the size of the earth, Millikan's oil-drop experiment, and Cavendish's weighing of the world. It certainly belongs in such heady company!

Interestingly, Young’s polymathy was not buttressed by any great skill in teaching or lecturing. We have a biography of Young, written by his friend George Peacock, a physics professor at Cambridge, that was published in 1855 (sixth image; the portrait we use appeared as a frontispiece to Peacock’s volume). Peacock clearly admired Young, but he freely admitted that Young was devoid of those special qualities that make a man an engaging speaker, and that his prose often lacked clarity. Our copy of Peacock’s biography was once owned by John F.W. Herschel, the great British astronomer and philosopher of science, and he wrote in pencil in the margin, next to Peacock’s observation that Young was not a “luminous and interesting writer,” his own observation: “He could never explain anything intelligibly that ever I asked him.” Herschel, nevertheless, was high elsewhere in his praise of Young’s wide-ranging achievements.

Young died at age 56, of unknown causes, although an autopsy revealed signs of atherosclerosis. Although he was not buried in Westminster Abbey (you will find his remains at St. Giles Church at Farnborough, Kent), there is a wall plaque in that venerable church honoring Young (seventh image). An excellent biography (despite its ridiculous title), written for the general reader, is The Last Man Who Knew Everything: Thomas Young, the Anonymous Polymath Who Proved Newton Wrong, Explained How We See, Cured the Sick and Deciphered the Rosetta Stone, by Andrew Robinson (2006), which we also have in our library.

Young’s work on deciphering hieroglyphics deserves further attention, especially since we have acquired his 1823 book on the subject, and we will try to explore this aspect of his career in a subsequent post on Young.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.