Scientist of the Day - Tobias Mayer

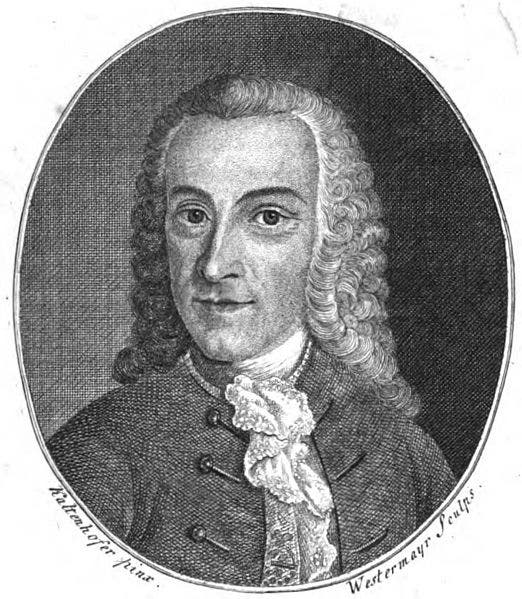

Tobias Mayer, a German astronomer, died Feb. 20, 1762; he was just 39 years old. Mayer was one of a surprising number of young lads who were born into a lower class working families and had no formal education, yet who managed to teach themselves mathematics and astronomy and rise out of their station, usually through the help of a patron - a local chaplain or military officer - who notices the boy's talent and sponsors his further education. Mayer, whose father was a cobbler, rose with the help of a series of benefactors to become one of the most adept mathematical astronomers of his day.

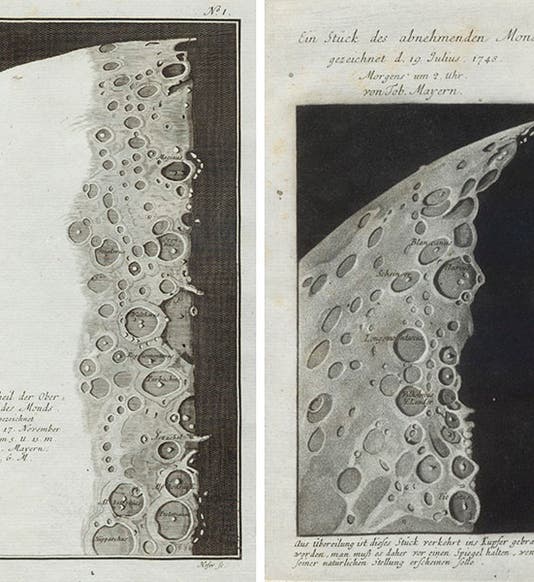

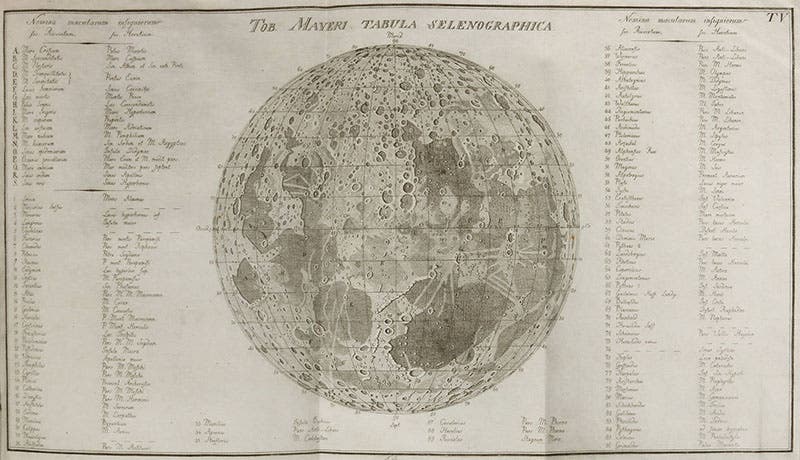

In 1748, he began a study of the lunar surface. He decided to improve the accuracy of luar maps by measuring the position of each lunar crater with a micrometer built into his telescope. The result was a kind of lunar gazetteer, with longitudes and latitudes for hundreds of lunar features, which he intended to turn into both a lunar globe and a lunar map. The globe was never finished, but a prospectus was issued in 1750 with two sample engravings.

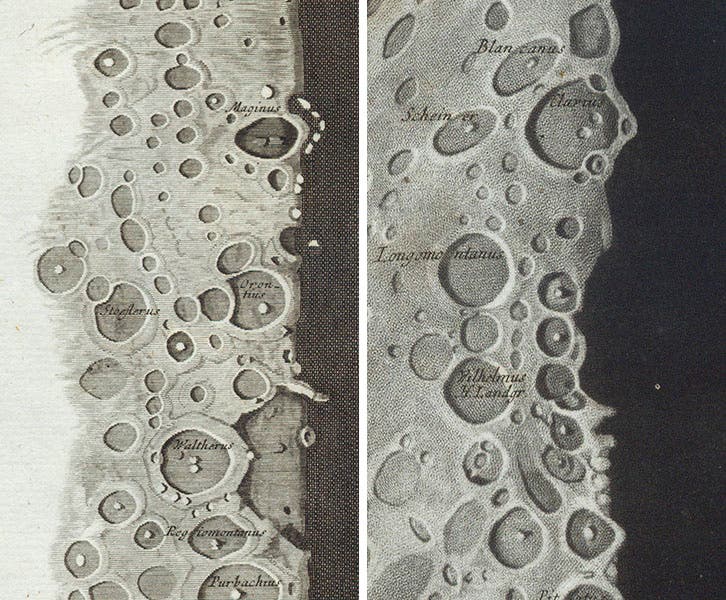

The prospectus, sponsored by the Nuremberg Cosmographical Society, was called Bericht von den Mondskugeln, and was published by the important Nuremberg map-making firm of J.B.Homann, for whom Mayer was working at the time. The book seems to be relatively scarce and we were fortunate to acquire a copy in 1988. Much of the 24-page pamphlet is technical, but the two engravings, showing segments of the proposed lunar globe, are stunning. The first is a conventional engraving and depicts some of the lunar highland craters, such as Maginus and Ptolemaeus. The second, unusually, is a mezzotint, showing the craters Clavius and Longomontanus. We displayed the mezzotint in our Face of the Moon exhibition years ago, but we show both of them here (first and second images), as well as two details (fourth and fifth images), so you can better appreciate the difference between a line engraving and a mezzotint.

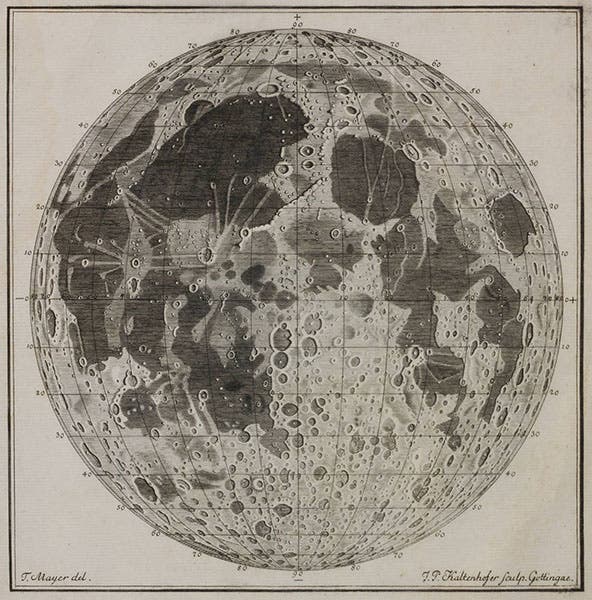

Mayer moved on to the Göttingen Observatory and there completed two lunar maps, one small and one large, both of unprecedented accuracy, since they were based on microscopic measurement. Unfortunately, death overtook Mayer in 1762 before he could put them into print. The smaller map was engraved by Joel Paul Kaltenhofer and printed in 1775 for Mayer's posthumous Opera, edited by George Christoph Lichtenberg; it was the best available moon map for 50 years (sixth image). Indeed, Johann Schröter, a perceptive lunar observer himself, instead of drawing his own map for his Selenographishe Fragmente (1791), simply turned Mayer's map upside down (preferring south at the top) and reprinted it (seventh image).

Mayer's larger map, drawn in ink, gathered dust in the Göttingen Observatory for 100 more years, until someone realized that the new technique of photolithography would enable the map to be printed without the expense of having it engraved. So in 1881, his large map and a number of his drawings were photographed and printed, and they are further testament to Mayer's observing skill and artistic talent. We have Mayer's Opera and the 1881 Tobias Mayer's grössere Mondkarte nebst Detailzeichnungen in our lunar cartography collection, along with the Bericht, so we were able to display all three works in the Face of the Moon exhibition. Here are the entries for the 1775 Opera and the 1881 grössere Mondkarte in that exhibition. As amazing as Mayer was as a lunar cartographer, there is much more of his career to showcase. The last plate in the Opera is a color triangle, visual evidence of an interest in color theory that is worth exploring. And Mayer's first work, the Mathematischer Atlas of 1745, is an astonishing folio of sixty engraved plates attempting to teach mathematics and all the mathematical sciences; even the explanatory text is engraved. We will examine this work, which for some reason is rarely discussed, and Mayer’s color theory, in a future post.

The house where Mayer was born in Marbach has been preserved as a museum, run by the Tobias Mayer Verein (eighth image). On their webpage there is a thumbnail of an intriguing color portrait, possibly the one by Kaltenhofer from which the 1799 engraving was made. It would be nice to find out more about it, and see it in a larger format. Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.