Scientist of the Day - USS Monitor

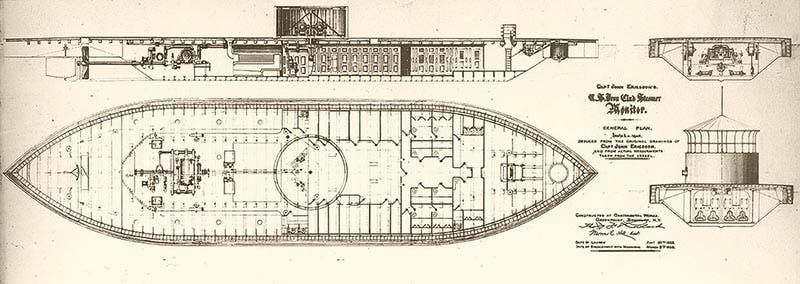

The USS Monitor, the world's first fully ironclad warship, was launched Jan. 30, 1862, in the first year of the American Civil War. It was designed by Swedish engineer John Ericsson for the Union Navy. Ericsson had moved to England in 1826 and promptly invented the screw propeller; then he crossed to the United States and designed the first screw-driven warship. After the start of the War, Ericsson designed the Monitor from scratch, a ship utterly different from any warship ever built, and submitted his design to the U.S. Navy. The Monitor was completely sheathed with iron plating 7 inches thick on the sides. It had a flat deck that was just inches above the waterline, so it presented very little of a target to enemy guns. One of its truly novel features was a revolving turret in the center of the deck, protected by thick iron panels, which housed two cannon that revolved with the turret and discharged their projectiles through small slots in the turret. The turret was not part of Ericsson’s original design, but rather the brainchild of U.S. inventor Theodore Timby.

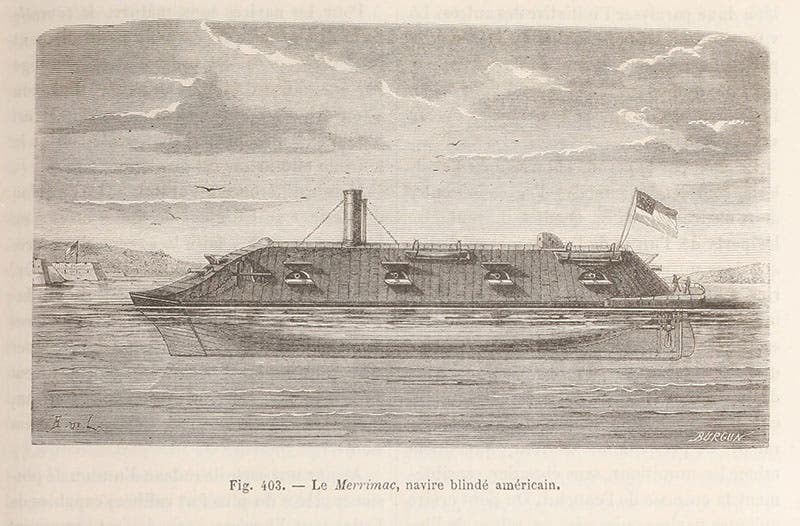

The Monitor was built in a Brooklyn shipyard in just 101 days, which is rather amazing; I have waited longer for a new driveway. The Monitor was 180 feet long and weighed in at about 1000 tons. It was a testament to steam power; large steam engines turned the screw, smaller steam engines raised and rotated the turret, and others powered the pumps. Not much more than a month after it hit the water, the Monitor was headed for its first naval engagement at Hampton Roads in southeast Virginia. The Confederate Navy had its own ironclad, the Virginia, which was different from the Monitor in that it was a conventional wooden warship, damaged by fire, that was given a new iron epidermis (before the skin graft, the wooden ship was known as the USS Merrimack). On Mar. 7, 1862, the Virginia had destroyed several Union ships at Hampton Roads. When the Monitor pulled into the harbor the next night, the Virginia found a much worthier opponent. In the Battle of Hampton Roads, as the confrontation of Mar. 8-9, 1862, is usually called, the two ships pummeled each other with cannon balls and shells to no real effect, and since neither ship’s cannons could penetrate the other's armor, the battle, which lasted about four hours, was essentially a stalemate. We have several visual records of the encounter: an actual photograph, which lacks a little in drama (first image), and quite a few retrospective chromolithographs, which have drama in spades (fifth image). In spite of the indecisive outcome, the future of naval warfare changed dramatically on that day. Both navies quit building wooden ships and immediately began constructing ironclads. The day of the wooden gunship was over.

The Monitor inspired an entire fleet of ironclads, but its own life was brief. On Dec. 31, 1862, just 11 months of age, the Monitor went down in heavy seas off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. The wreck was discovered in 1973, and some 200 tons of parts and machinery have since been recovered, including the engine, the anchor, the propeller shaft, and the innovative turret with its two massive guns (sixth image). It is hard to look at that turret and realize that during the four-hour battle, it held 2 officers and 17 enlisted men, and fired its pair of cannons 41 times, while the turret was struck by enemy fire at least a dozen times. Everyone must have been bruised, black with soot, deaf, and absolutely terrified. And all that for a stalemate.

The wreck site was designated a National Marine Sanctuary in 1975 (the first such sanctuary) by the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and NOAA then consigned all the recovered Monitor parts to the Mariners’ Museum in Newport News, Virginia. The Museum in turn established the USS Monitor Center to house all the artifacts. Since those are mostly large chunks of iron that spent 140 years under water, they have to be housed in large tanks filled with water until they can be slowly restored. Outside, in front of the Center, is a large, full-size replica of the Monitor, which is quite impressive in its red-and-black coat of paint.

Seven years ago, in the early days of this forum, I published a post on Ericsson. It was not very good, because it was too brief; I should have devoted more space to Ericsson and less to the Monitor and Hampton Roads. And, like all those early posts, the images had no captions. But it is still worth looking at, because it has two fine photos of statues of Ericsson, the best lithograph surviving of the battle of the Monitor and the Virginia, and a view of the Monitor replica at the Mariners’ Museum. Some day I will rewrite and expand the text, provide captions, and perhaps add a little something about Timothy Timby, the unsung inventor of the ingenious rotating turret.

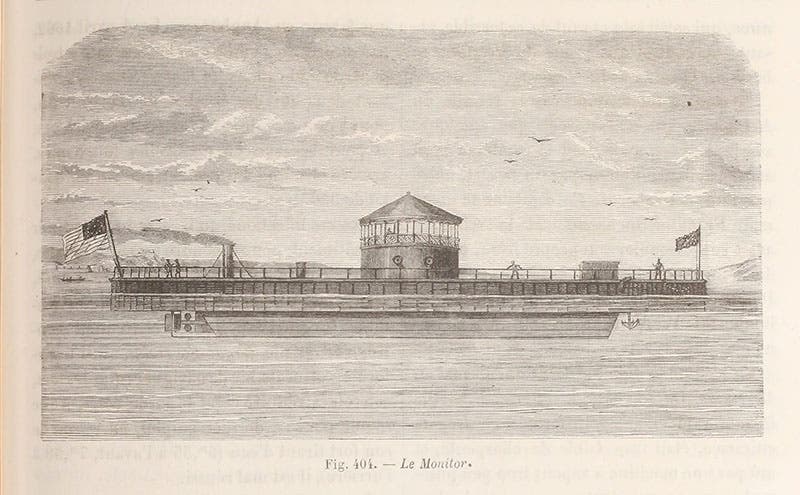

If you do an image search for USS Monitor, you will not (at least I did not) turn up a wood engraving that appeared in Louis Figuier’s Les merveilles de la science (1867), a set of volumes we have drawn upon many times for images of inventions. As illustrations go, it is not a great one, but since it does not seem to have been reproduced online, we do so here (third image). We also include the companion wood engraving of the CSS Virginia, identified in the caption as the Merrimac (fourth image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.