Scientist of the Day - Walter Charleton

Walter Charleton, an English physician and natural philosopher, was born Feb. 13, 1619. Charleton was a physician for King Charles I, when he and Charleton were both at Oxford, and before Charles was beheaded, and then for Charles II, when he was in exile in France during the Commonwealth. It was while in Paris that Charleton encountered the philosophy of Pierre Gassendi, and his disciple (at least initially), Thomas Hobbes.

The 1640s saw the emergence on the Continent of what we call "the mechanical philosophy," as two great French philosophers, in different ways, argued that the only acceptable forces in nature are those that result from matter contacting other matter – all other forces, such as sympathies, and action at a distance, were disallowed. René Descartes proposed that matter filled the universe, even the part we think of as empty, and this swirl of matter causes planets to move in their orbits and compasses to point north. Gassendi, on the other hand, drew on the ancient philosophies of Democritus and Epicurus and thought that matter consists of atoms that move through a void, and that everything we see and experience is just the result of the changing arrangements of atoms in space.

Gassendi was a good Catholic – a priest in fact – so the principal problem he faced in making atomism acceptable to Christians was to dispel the atheism implicit in the writings of ancient atomists, who claimed that atoms were infinite in number, had always existed, and were each imbued with their own inherent motion – there was no need for a divine agency in such a world view. Gassendi maintained that atoms had been created by God, a finite number of them, and they were put in motion by God as well. Providence was thereby reintroduced into the world of atoms. Gassendi described his atomistic mechanical philosophy in Animadversiones in decimum librum Diogenis Laertii (Observations on the Tenth Book of Diogenes Laertius [a biography of Epicurus], 1649), which contains a treatise, Philosophiae Epicuri syntagma, which described the system of Epicurus as modified by Gassendi.

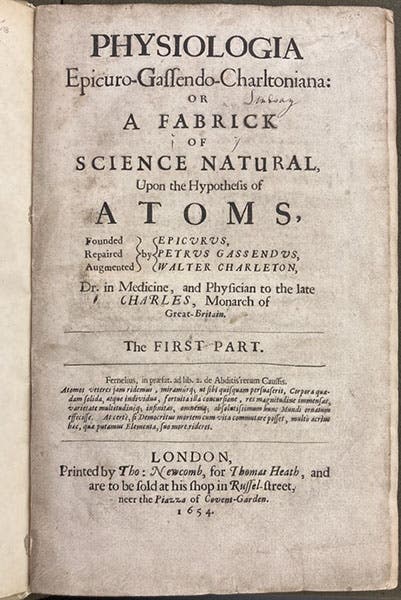

Charleton was exposed to both versions of the mechanical philosophy in France, and he chose atomism because it fit better with his own Christian beliefs. When Charleton returned to London, he found that Gassendi’s 1649 book was not readily available, and that Gassendi’s atomism was misunderstood and considered to be irreligious. So Charleton set out to write a book, in English, that would show how the ancient atomism of Epicurus had been successfully modified by Gassendi, so that God was necessary, as the creator of atoms and the one who put them in motion. Now if you wrote such a book, what would you call it? A modern academic publisher would probably choose something like: Godly Atoms: How Gassendi Crafted a Christian Mechanical Philosophy from the Wreckage of Epicurean Atomism, by Walter Charleton. What did Charleton call his book? He chose: Physiologia Epicuro-Gassendo-Charletonia. Much more concise. Unfortunately, he could not resist adding a subtitle: … or, A Fabrick of Science Natural, upon the Hypothesis of Atoms Founded by Epicurus, Repaired by Petrus Gassendus, Augmented by Walter Charleton. It was published in 1654, and we have this sizeable folio in our history of science collections (second image).

Charleton’s Physiologia was the first book on continental atomism published in England. Hobbes would soon follow with his own treatise, but the atomism of Hobbes, the “monster of Malmsbury,” was denounced in England as atheistic, which indeed it was. Charleton’s was a gentler atomism, much more palatable to people like Robert Boyle and Isaac Newton, both of whom came to subscribe to a “corpuscular philosophy.” Charleton also appealed to Boyle and Newton because Charleton, in 1652, had published one of the first treatises on natural theology, The Darkness of Atheism Refuted by the Light of Nature, and as Boyle would later become the father of English natural theology, Charleton might qualify as perhaps a wise uncle. We do not have Charleton’s Darkness of Atheism in our collection, but we should, as we have strong holdings in natural theology.

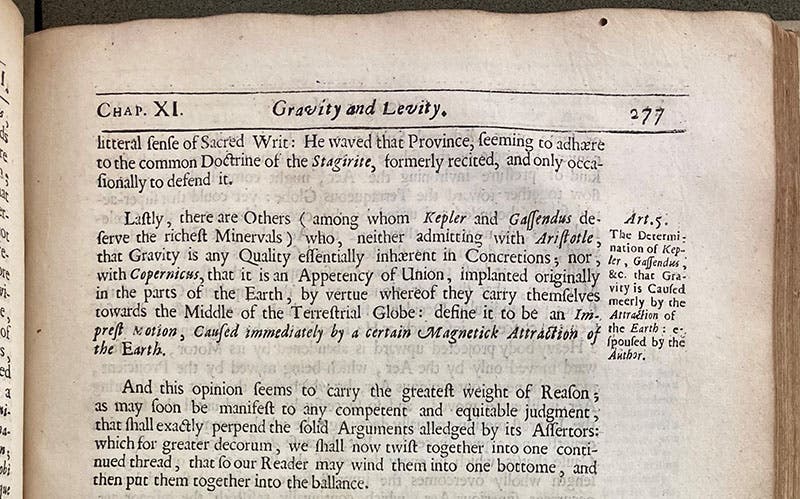

We show here, in addition to the title page of the Physiologia, a detail of a page that includes a discussion of gravity, just as a sample of Charleton’s scientific prose (third image). Gravity for Aristotle was a quality of matter, heaviness, and things fell to Earth because it was their nature to do so. Charleton states, quite clearly, that gravity is a result of the attraction of the Earth. One can see why Newton might have liked this book.

Charleton went on to become one of the early fellows of the Royal Society of London, and eventually a fellow of the Royal College of Physicians of London, which owns his portrait (first image). He published a book of natural history in 1668 that we discussed in an earlier profile of Charleton, posted on his birthday six years ago. Perhaps his best-known treatise is another one that is lacking from our collection, Chorea Gigantum (1663), a book about Stonehenge, in which he argued that Stonehenge was probably built by the Danes. That one we are never likely to obtain, as it really is out of scope for us.

Charleton lived to the considerable age of 88, dying in 1707. He was buried in St. Paul’s Churchyard, London. I have been unable to find a photo of his gravestone, or to learn if the precise location of his grave is known.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.