Scientist of the Day - Watson Cheyne

William Watson Cheyne, a British surgeon and bacteriologist, was born Dec. 14, 1852, on a ship moored off Hobart, Tasmania. He grew up on the island of Fetlar, one of the North Isles of Shetland, north of Scotland, perhaps a descendant of the Vikings that originally populated the area. Cheyne wanted to go to sea, like his father, and thought that medical training would provide a livelihood on a ship of the realm. Half of that plan would work out. He went to Aberdeen for further schooling, and then to the University of Edinburgh medical school. It was there, on his lunch break, that he first heard Joseph Lister lecture. Lister spoke about the importance of antisepsis for surgery, and Cheyne was a convert, for life, as it turned out. Upon graduating, Cheyne became resident surgeon for Lister, and when Lister moved in 1877 to King's College Hospital in London, he took Cheyne with him. The two would be surgeons there until Lister retired in 1895, and for Cheyne, for 27 years beyond that.

In 1861, Louis Pasteur had proposed the germ theory of disease, arguing that specific bacteria cause specific diseases. This was a great stimulus to medicine on the continent, as bacteriologists, such as the German Robert Koch, followed up on Pasteur, but hardly anyone noticed in England except Lister. He made the case for surgical antisepsis, advocating the use of carbolic acid to sterilize surgical instruments and wounds in the 1860s. He acquired a following in Edinburgh, but when he moved to London, all he found was antagonistic opposition, as few there in the 1870s accepted the idea that bacteria cause disease.

This is where Cheyne entered the picture. Twenty-five years younger than Lister, he entered the fray enthusiastically. He published Antiseptic Surgery: Its Principles, Practice, History and Results, in 1882, and Lister and His Achievements in 1885. He also translated the 1878 book by Koch on wound infections into English and had it published in 1880. As his own surgical practice slowly built up, Cheyne applied Lister's principles of antisepsis to his own operations, and with great success. He visited Koch and worked in his lab in 1886, and became much more of a bacteriologist than Lister ever was. He also put much more emphasis on asepsis than Lister did, maintaining that keeping the operating theater free of germs was just as important as killing infectious agents in the wound. When he retired in the early 1920s, Cheyne was as famous as Lister had been, as well recognized for his contributions to antiseptic surgery, and just as honored with baronetcies and the like.

Since we do not collect medical or surgical works, we do not have any books by Cheyne in our collections. There are several recent biographies, but we do not have any of those either. However, the title of Jane Coutts 2015 biography intrigued me: Microbes and the Fetlar Man: The Life of Sir William Watson Cheyne. I wondered what it meant to be a Fetlar man. Cheyne clearly loved the tiny island where he was raised; he built a home there, Leagarth House, in 1901, and retired to it in 1922, living his final decade there (third image). It turns out that the island once supported about 900 inhabitants, but most of them were infamously evicted in the 1820s in favor of sheep-herding, and the current population is about 60. Not surprisingly, when you look for the “Notable People” section in the Wikipedia article on Fetlar, you find instead one called “Famous Son,” and Cheyne is it. But if you can only have one famous resident, Cheyne would be a good choice.

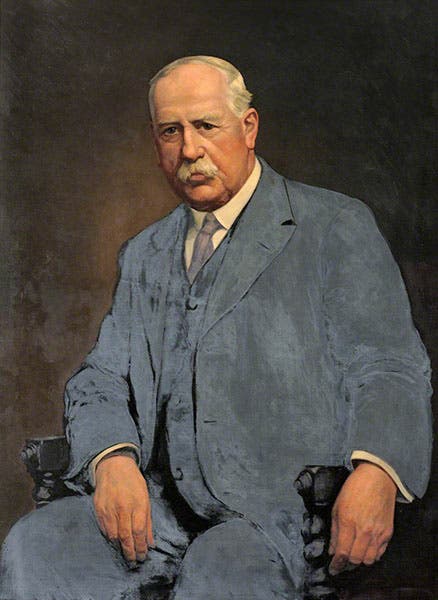

There are quite a few portraits of Cheyne that were painted or photographed over the years; he really was quite well known and respected in English society. We include two, one painted by William Charles Penn in 1906, and now at the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh (first image), and the other painted in 1928 by Herman Salomon, and now in the Wellcome Collection in London (second image)

I must conclude by quoting a sentence from the Wikipedia article on Cheyne:

“‘Cheyne has also been immortalized in the naming of the commonly used Vascular Surgery instrument the 'Watson Cheyne Dissector', which is used in endarterectomy procedures to help separate atherosclerotic plaque from the arterial wall. The instrument usually is constructed with two differing tips, a probe tip and an elevator tip.”

Man, if that isn’t immortality, I don’t know what is.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.