Scientist of the Day - Willem Piso

Willem Piso, a Dutch physician and botanist, died, or was buried, on Nov. 28, 1678. Although his Dutch name was Pies, he is almost always referred to by his Dutch first name and his Latinized last name. In 1637, Piso joined the Dutch settlement in Recife, Brazil, established by Johan Maurits van Nassau, where Piso took on the role of company physician. He was also expected to study the local flora and determine their value, if any, for medicine. His zoological counterpart was George Markgraf (often Marcgraf), who studied the animals. Both men were assisted by several capable artists, most notably Frans Post and Albert Eckhout.

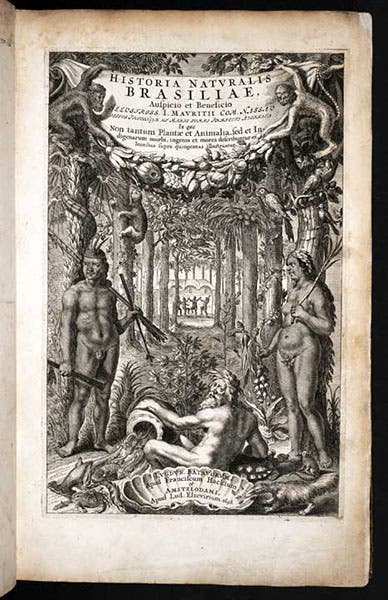

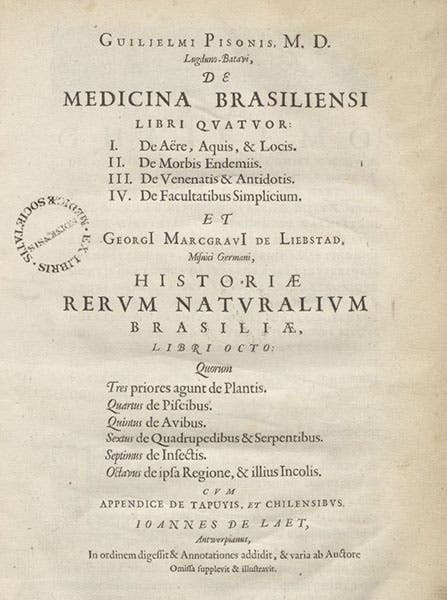

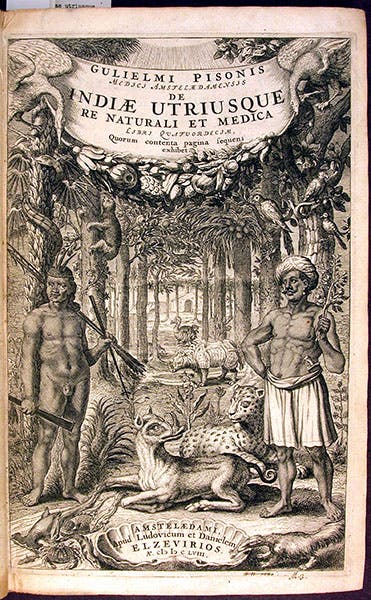

After seven years, Maurits returned to Amsterdam in 1644 with Piso and the rest of his entourage, except for Markgraf, who was sent on to Dutch Angola in Africa, where he died almost immediately. Piso compiled his notes and assembled the artists’ paintings and wrote the four medical botany chapters for a sumptuous publication that was put together by Johannes de Laet, a stay-at-home but competent editor. Published in 1648, it was called Historia naturalis Brasiliae, the Natural History of Brazi., the first book published in Europe on the natural history of a foreign country. The splendid engraved title page (second image), mentions only Maurits, but the typeset title page that follows, which we show here (third image), lists the contributions of Piso, Markgraf, and De Laet. We have published a post on Maurits and a post on Markgraf.

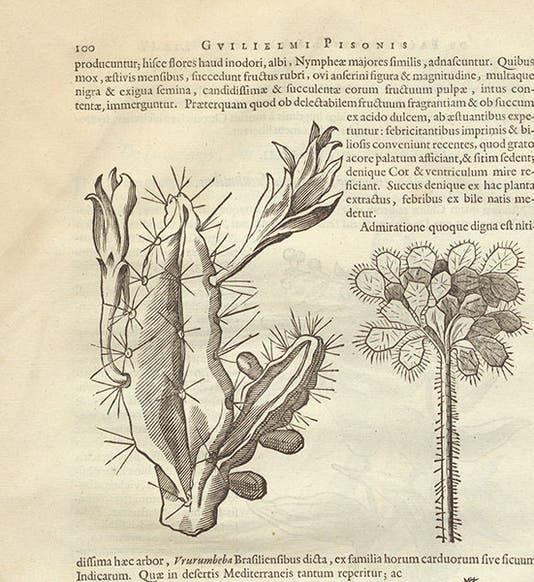

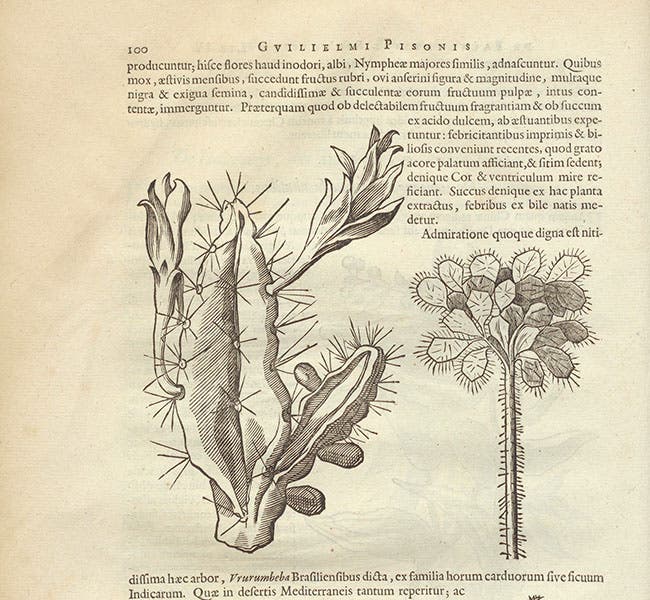

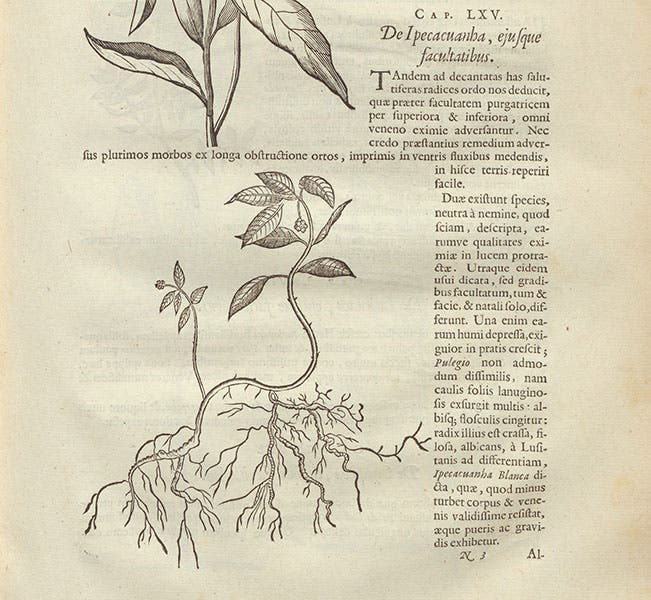

The woodcuts of plants in Piso's chapters are beautiful, and many of them are the first depictions ever in print. We show two of Piso's articles here, with their woodcuts, one on the prickly pear (first image), and another on ipecacuanha, a plant that locals used for an emetic (fourth image).

So far, all was well and good with Piso, except that in his introduction to his 1648 chapters, he referred to Markgraf as his domestic, which did not sit well with Markgraf's relations (Markgraf himself was dead and could not complain). However, in 1658, Piso issued a second edition of the Natural History of Brazil, adding in an account of the East Indies by Jacob Bontius, thus justifying the new title: De Indiae utriusque, [Natural History] of the Two Indies. For this edition, Piso kept all of Markgraf's material, but he left Markgraf's name out, making it appear as though Piso had written the entire Brazilian section himself. This irritated many admirers of Markgraf's work, and supposedly also Linnaeus, who named a particularly nasty plant, the seeds of which entrap birds, Pisonia.

One interesting feature of the second edition is that the copper plate for the engraved title page of the first edition was reused for the second, but changed in certain spots to show animals and peoples of the East Indies as well as the West Images (fifth image). It is unlikely that Piso had anything to do with this; it was more likely the idea of the printers, the Elzevir brothers, who owned the plate. We have also written a post on Bontius, where you may see a detail of the engraved title page.

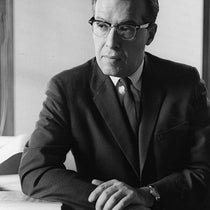

Piso seems to have prospered well enough in the Amsterdam medical community after his return from Brazil, and grew in size, if not in reputation, if his portrait of 1662 is any indication (sixth image). He is often said to have been a pioneer in tropical medicine, but I am not sure that there is any evidence of that. There really was no tropical medicine to speak of in the 17th century.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.