Scientist of the Day - William Carlos Williams

William Carlos Williams, an American physician and poet, died Mar. 4, 1963, at the age of 79. Most people who are familiar with 20th-century poetry, and who know or have heard of T.S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, and Robert Frost, will know Williams, at least by name. But many are not aware that Williams was, by profession, a doctor. To be more specific, he was a pediatrician, and was in fact Chief of Pediatrics at Passaic General Hospitals in New Jersey for almost 40 years. There have been quite a few writer-physicians over the years – Arthur Conan Doyle, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Anton Chekhov, and in our own time, Walker Percy, Robin Cook, and Michael Crichton. But Williams might have been the most gifted and creative of them all. Williams was one of the Imagist poets, who rebelled against the intellectualism of poets like Eliot, and who sought to write simple poems that painted pictures and did not require any reference works for comprehension. I have no credentials as a literary critic and will not attempt to analyze any of Williams’ poems. But there are several that I like, and I see nothing wrong with pointing them out. You may seek expert guidance elsewhere if you wish to do so.

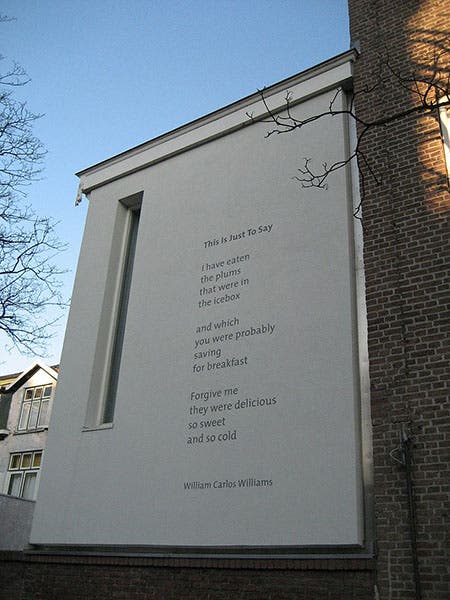

One of Williams’ early published poems, which appeared in Spring and All (1923), was titled “XXII” in the volume, but is often referred to as "The Red Wheel Barrow. It won't take up much space to include the entire poem here: so much depends upon a red wheel barrow glazed with rain water beside the white chickens If ever a poem were a word-picture, this is it. You may analyze its word choice if you wish, and its shape, but beware of looking for the story behind the poem, for you are sure to get it wrong, as many experts did for years, and anyway, it is hardly relevant to the poem’s effect. Another well-known Williams poem is called "This is Just to Say," and it was published in Collected Poems, 1921-1931 (1934). Here are all 12 lines and 28 words: This is Just to Say I have eaten the plums that were in the icebox and which you were probably saving for breakfast Forgive me they were delicious so sweet and so cold It is hard at first to distinguish the poem from a note pinned to a refrigerator by a magnet, but when you read it again, you start wondering about the person who ate the plums, and whether he is apologetic, or instead pleased with him- or herself. And you cannot help but admire that crisp final stanza, although it seems so simple. A range of reactions to the poem is possible, and if you want to be exposed to some of them, watch this episode from the PBS show Poetry in America from several years ago, where 4 poets and 5 ordinary couples mused about what the poem means to them for nearly 30 minutes.

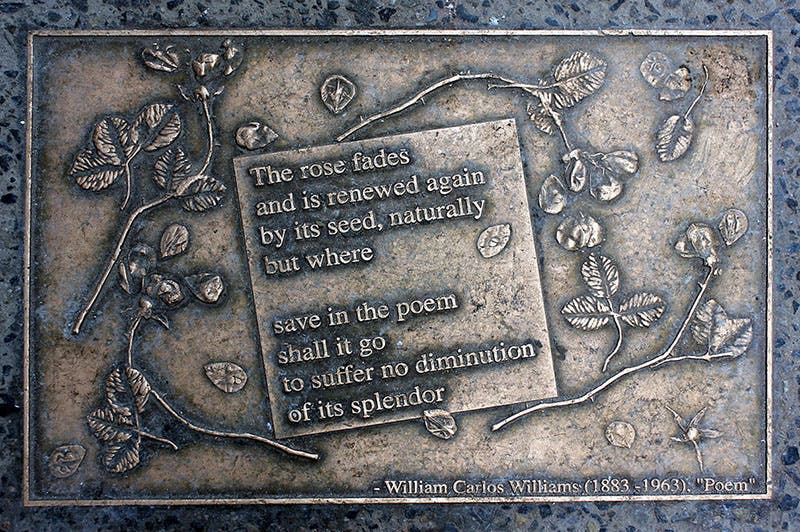

For reasons unknown to me, “This is Just to Say” has been carved into stone, in English, and mounted somewhere in the Hague (third image, just above). It clearly has some sort of universal appeal. A third Williams poem, which appeared, untitled, in Pictures from Brueghel and Other Poems (1962), we do not need to transcribe here, since you can read it right off the sidewalk plaque that has been put in place on Library Walk in New York City (fourth image, just below).

How Williams managed to turn out such a steady stream of high-quality poems over a fifty-four-year period while maintaining a full medical practice is a mystery to me. I have a daughter who is a pediatric physician, and I have not noticed that she has a lot of time free for the pursuit of a second calling, especially one that requires intense concentration, which writing poetry certainly does. Williams was remarkable in being able to lead two full lives, all at once.

Passaic General Hospital is now St. Mary’s Hospital and still going strong, after some rough times. We show a postcard of the original hospital as it appeared around the time Williams started there (second image). His house in Rutherford, where he and his wife lived for 50 years, is now on the National Register of Historic Places (fifth image). His poems? They are everywhere. Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.