Scientist of the Day - William Charles Wells

Linda Hall library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

William Charles Wells, an American-born Scottish physician, was born May 24, 1757. Wells is hardly ever honored in anniversary notices like these because of the dearth of relevant graphic material--there is no known portrait of Wells, no gravestone, no blue plaque. He published hardly anything during his lifetime, and the posthumous publications do not include a single illustration. As the images above scroll by, you will see what we mean. But we are making a space for Wells because he deserves commemoration, since he was the first person to propose what Charles Darwin would later call natural selection.

In 1813, Wells read a paper to the Royal Society of London, occasioned by a white female patient with splotches of dark skin. In his paper, Wells speculated about the origin of skin color variations in humans. He suggested that long ago, there might have arisen in equatorial regions a variety of humans that were better able to resist diseases such as malaria, perhaps aided by darker skin, and they survived where other variations perished. Similarly, lighter-skinned humans might have been variations that were better able to survive in temperate and arctic regions.

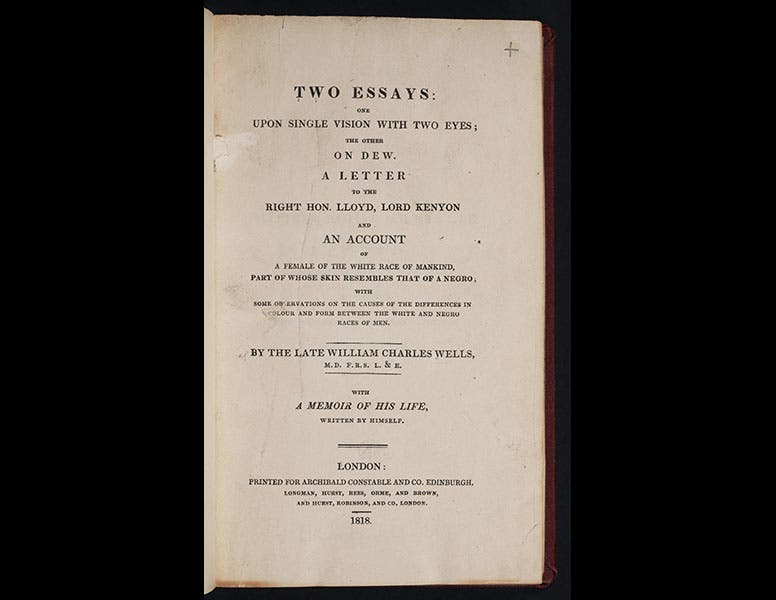

Wells’ paper was not printed in the Philosophical Transactions, but after he died in 1817, two of his treatises, "On Single vision with Two Eyes," and "On Dew", were published posthumously, and Wells’ brief "Account of a white female, part of whose skin resembles that of a negro" was added on at the very end. No one noticed, certainly not Charles Darwin, who was 9 years old at the time.

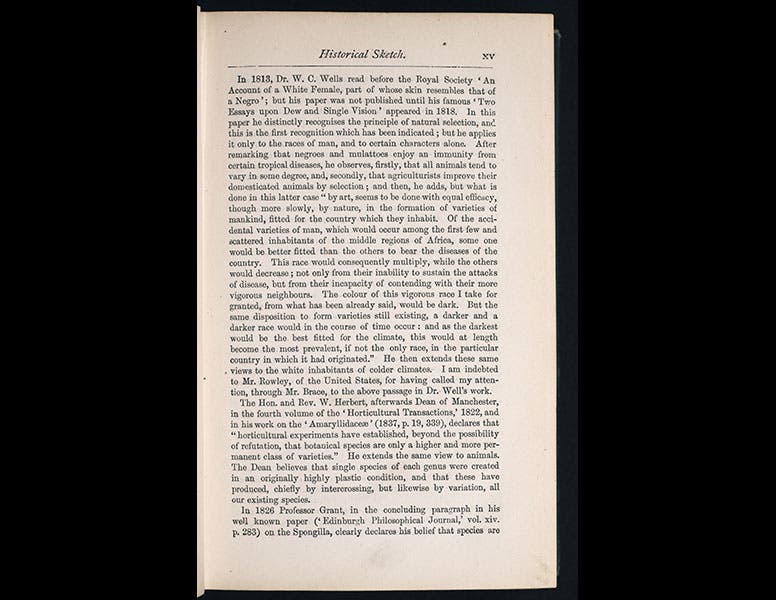

Time went by, Darwin discovered natural selection on his own in the late 1830s, and he sprang it on the world in On the Origin of Species in 1859. During the year after publication, various readers noticed that certain aspects of Darwinian evolution had been anticipated by such naturalists as Étienne Geoffroy St. Hilaire, Patrick Matthew, and the anonymous author of the Vestiges. So in 1861, for the third edition of the Origin, Darwin added an “Historical Sketch” in which he discussed his precursors and to what extent they anticipated his own work (third image). Geoffroy St. Hilaire, Matthew, and the Vestiges all merited a paragraph in the “Historical Sketch.” But there was still no mention of William Wells.

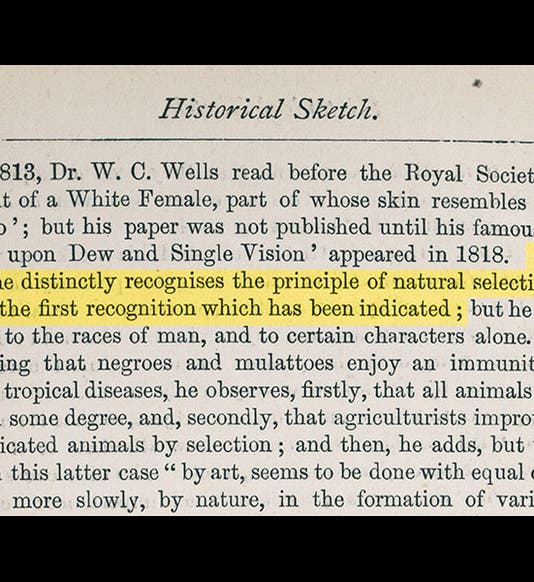

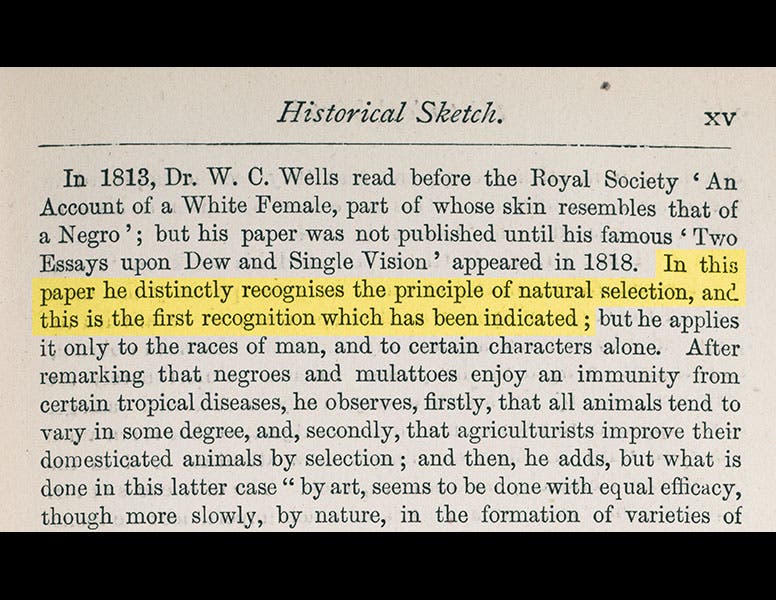

Then, sometime before 1866, an American, Robert Rowley, drew the attention of an Englishman, Charles Loring Brace, to Wells' paper, and Rowley conveyed the information to Darwin. Darwin was apparently impressed. For the fifth edition of the Origin, he revised the “Historical Sketch”, and he added a paragraph about Wells, in which he commented: "In this paper he [!wells!] distinctly recognises the principle of natural selection, and this is the first recognition which has been indicated." Darwin also pointed out, quite correctly, that Wells used natural selection only to account for human races, not to explain the origin of species. But still, Wells was the only precursor of natural selection that Darwin took seriously. And that is why Dr. Wells gets a birthday commemoration on this day.

We have Wells’ Two Essays, with its important appendix, in the History of Science Collection; we show the title page above. We also have the fifth edition of the Origin, but in that printing, the paragraph on Wells is split over two pages, so we show above the relevant page from a slightly later edition (1873; fourth image), in which Wells has the top of the page all to himself; in a detail (first image), we have highlighted Darwin’s sentence of praise.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.