Scientist of the Day - William Hodges

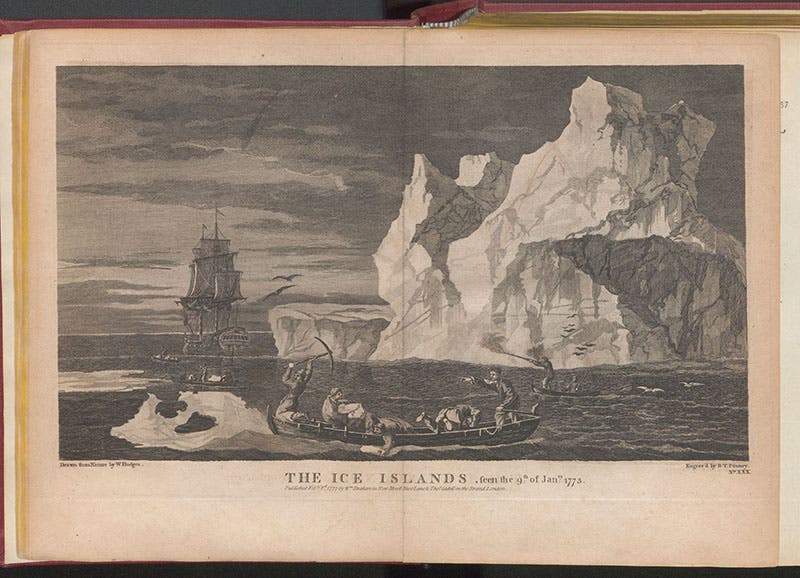

William Hodges, an English artist, died Mar. 6, 1797, at age 52. Hodges was the first professionally trained landscape painter to be invited to accompany a voyage of exploration as ship's artist. In Hodges case, the expedition he joined was the second voyage of Captain Cook, 1772-75, probably the most significant and influential voyage of the entire 18th century. Hodges made many memorable landscapes of Tahiti, New Zealand, Easter Island, and the like. What distinguished Hodges from the typical resident ship’s artist was, first of all, his artistic skill, and secondly, his sensitivity to atmospheric light and texture. The clouds in his landscapes are marvelous to behold, as we see in A View of Matavai Bay, an oil now in the Yale Center of British Art (third image).

Hodges also brought some classical tradition to his compositions, as in his depiction of the monuments on Easter Island (Rapa Nui), where the skull evokes the theme of “Et in Arcadia ego” (“I [death] am also in Arcadia”) made famous by Nicolaus Poussin (first image)

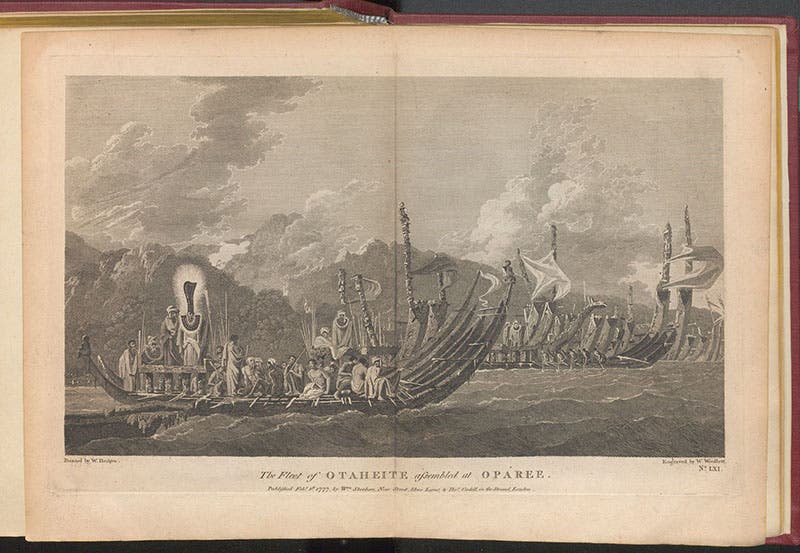

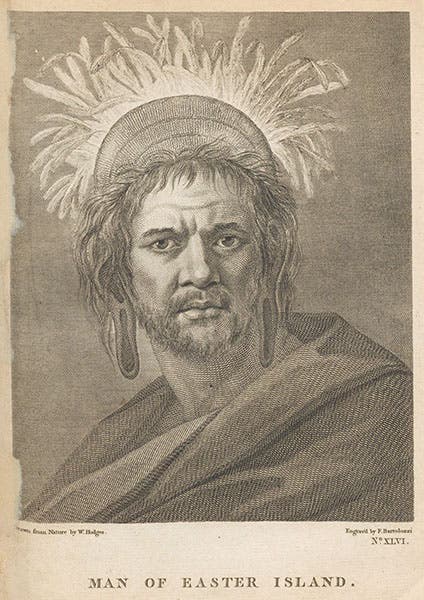

One of the reasons for having a shipboard painter was to provide illustrations for the published narrative of the voyage. Our fourth image depicts Hodges painting of the war canoes of the Tahitians, and our fifth the engraving after the painting that appeared in James Cook’s Voyage towards the South Pole and Round the World, of which we have only a fourth edition, published in 1784. Unfortunately, for Hodges, the engravers employed for the publication of the second voyage had a classical bent and insisted on redoing Hodges’ sketches so that the natives ended up looking like classical Greek figures. This did not affect the landscapes too much (although they certainly lost their diaphanous quality), but it radically altered the portraits of the natives, such as his depiction of an Easter Islander (sixth image).

Hodges made some of his paintings on the spot, some on the return voyage, and some back in London. Experts can tell the difference by his color palette; Hodges was limited in his pigment choices on board ship, so the most richly colored paintings were executed after he returned.

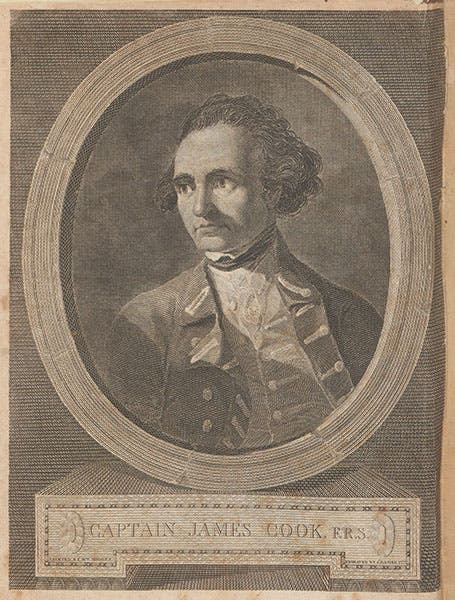

Hodges also painted a portrait of his captain. The original oil is in the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich. An engraving after the portrait appeared as the frontispiece to Cook’s narrative (eighth image).

A major exhibition of Hodges’ work was mounted in 2004 by the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich; the exhibition travelled the next year to the Yale Center for British Art in New Haven, Conn. The massive catalogue, William Hodges, 1744-1797: The Art of Exploration, ed. by Geoff Quilley and John Bonehill, is still in print and available.

Hodges later spent 4 years in India and produced many further paintings as a result. But we do not have anything pertaining to the time in India in our collections. Hodges did quite well as a painter for a while, but he fell out of favor with the royal family as a result of an exhibition he did on war, and his reputation plummeted. He also made some unwise financial investments. His early death may have been natural, or may have been hastened by his own hand.

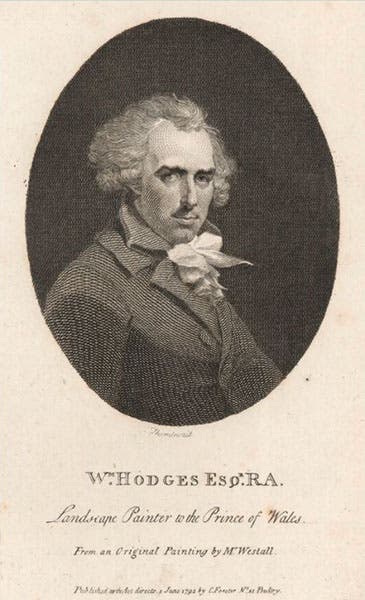

There are several portraits of Hodges; the one we show here (second image) was engraved after a painting by Richard Westall, an up-and-coming portrait artist, and the younger half-brother of William Westall, who would follow in Hodges’s path as the artist on board the Investigator, as part of the Flinders voyage, 1801-03.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![A View of the Monuments of Easter Island [Rapa Nui], oil on canvas, by William Hodges, ca 1776, Royal Museums Greenwich (collections.rmg.co.uk)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/64591c7b-0586-44bb-896f-176052b18c34/hodges1.jpg?w=534&h=582&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)

![A View of the Monuments of Easter Island [Rapa Nui], oil on canvas, by William Hodges, ca 1776, Royal Museums Greenwich (collections.rmg.co.uk)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/6c7ea330-2378-404a-92c0-268193cc71b0/hodges1.jpg?w=800&h=491&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)

![A View of Matavai Bay in the Island of Otaheite [Tahiti], oil on canvas, by William Hodges, 1776, Yale Center for British Art (britishart.yale.edu)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/d83c98b7-788a-4fcb-b6b1-7f04df5ac781/hodges3.jpg?w=800&h=531&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)