Scientist of the Day - William Kennett Loftus

William Kennett Loftus, an English archaeologist, was born on Nov. 13, 1820, in Linton, Kent, not far from Maidstone, where Gideon Mantell would be digging up Iguanodons in a few years. He studied geology at Cambridge, and then, in 1849, he signed on with the British Turco-Persian Boundary Commission, which gave him a chance to investigate and, in a few cases, excavate, some of the Babylonian and Assyrian ruins discovered by Henry Layard at Ur and Nineveh in what is now Iraq. Loftus is said to have discovered the Ziggurat of Ur, and the nearby ruins of a contemporary city, Uruk, in 1849. In fact, he says as much in a book he wrote about his adventures, Travels and Research in Chaldaea and Susiana … in 1849-52 (1857). Although we have two of Layard's accounts, we do not have the book by Loftus in our collections.

Layard left the excavations at Nineveh and Nimrud (part of modern-day Mosul) in 1852 to enter diplomatic service, and he was succeeded by a native Assyrian, Hormuzd Rassam, who found the Library of Ashurbanipal and collected tens of thousands of cuneiform tablets for the British Museum, including the first substantially complete copies of the Gilgamesh Epic and the Enuma Elish creation poem. We have written a post on Rassam. But he too left for the diplomatic corps in 1854, and his place was taken by Loftus.

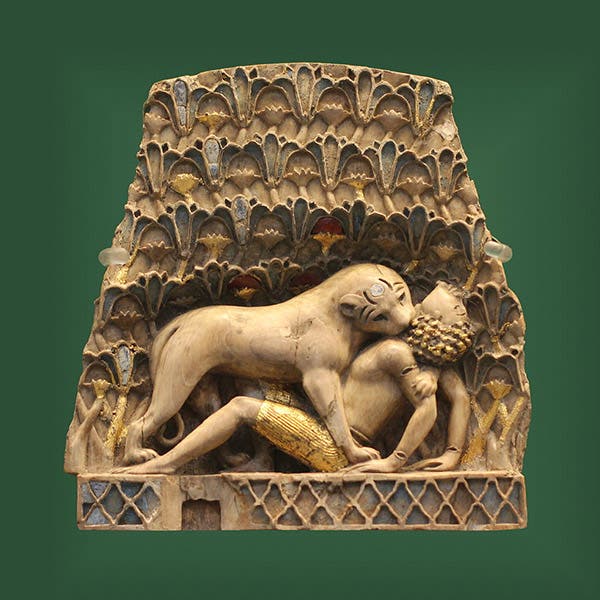

Loftus discovered a new palace at Nimrud, which he called the south-west palace at first, and later the Burnt Palace, since much of it had been destroyed in a fire. In one of the rooms there, he found the first of what we now call the Nimrud ivories. These are very famous objects in Assyriology. They consist of small carvings of elephant ivory, delicately wrought, some in the shape of human figures, intended for handles for a knife or mirror, others flat reliefs that might have been set into tabletops or the backs of chairs and thrones. Loftus found about a thousand, mostly fragments, but some intact. Many thousands more are now known.

The most curious feature of the Nimrud ivories is that when they have inscriptions, they are in Phoenician script, not Assyrian, suggesting that the artisans were Phoenicians. And yet no ivories like the Nimrud ivories have been found in Phoenicia (modern Lebanon) or in any of its many Mediterranean colonies. It is a mystery to this day.

All of the ivories Loftus found ended up in the British Museum, although I am not sure how or why, since he was not employed by the Museum. But the Museum also has Nimrud ivories recovered by many later archaeologists, especially those found by Max Mallowan in the 1950s, many of which are exquisite. Most of the articles on Loftus have been illustrated with artifacts found by Mallowan. Searching the British Museum Collections website, I found several ivories with accession dates of 1856, which could only be ones found by Loftus, and I show them first. The record now straight, I can in good conscience now include two later examples of Nimrud ivories found by Mallowan, including the most famous piece of all, depicting a lion attacking a man (fifth and sixth images). Since Mallowan was married to, and was assisted in the field by, mystery writer Agatha Christie, we shall have to write a post on Mallowan sometime soon.

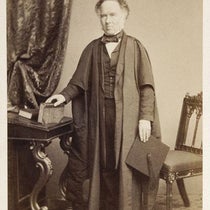

The life of Loftus had little time left to run. In 1856, he transferred to the Geological Survey of India, but he grew sick in India and was sent back to England, dying on the voyage home. He was 38 years old and was, I believe, buried at sea. Only the one portrait, a photograph, and not a very good one, survives (second image). But we do still have the Nimrud ivories to remember Loftus by, which, for the moment, are staying in the British Museum.

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.