Scientist of the Day - William Mason

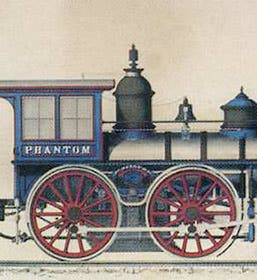

William Mason, a American mechanical engineer and manufacturer, was born Sep. 2, 1808. Mason was a whiz at designing machinery, all kinds of machinery, and in 1845, he established a manufacturing plant in Taunton, Mass., and began producing a variety of machines for the American textile industry. But Mason also built locomotives, and since I am a great admirer of vintage locomotives, that will be our focus for today. The American locomotive industry was already well established when Mason came on the scene. Matthias Baldwin, some 13 years older than Mason, had founded a large factory in Philadelphia that began turning our locomotives in the late 1830s, and fine engines they were. But Mason, beginning in 1853, would build locomotives as elegant as those of Baldwin, and perhaps more so. Both Baldwin and Mason believed that locomotives should be beautiful and stylish. Mason added the criterion of being "clean" - unencumbered by frills and ornament. He also brought a certain classicism to locomotive engineering, using elements of ancient Tuscan and Doric orders in his designs. For example, locomotives after 1850 had two domes on top of the boiler – a larger steam dome, which housed the steam valves, and a sandbox, containing sand for the wheels when needed. The sandboxes and steam domes on Mason's engines were classically inspired, ringed with moldings and quite clean. We see above an 1856 Mason locomotive, the Phantom (first image). The steam dome is the larger one, nearer the cab; the sandbox is between the steam dome and the stack. They are handsome additions to the boiler. All of the details on a Mason locomotive were finely finished, as if they were intended for a house interior and not a railway yard. In 1873, Mason began manufacturing a version of an English locomotive called a Fairlie or Bogie, with the drive wheels on a swiveling bogie. The original Fairlie was double ended; Mason removed the rear drive wheels and substituted a large trailing truck, leaving the remaining drive wheels far forward. In the parlance of locomotive taxonomy, the Mason Bogie was a 0-6-6, with no front truck, 6 drive wheels, and 6 wheels on the trailing truck. With its swiveling drive wheels, it could navigate sharp curves and was especially suitable for the winding railways in the mountains of the West, usually in narrow-gauge format. We see here a vintage photograph of one manufactured in 1874. Quite a few Mason Bogies were built and at least one survives in working order, the Torch Lake, which shuttles passengers around Greenfield Village in Dearborn, Michigan.

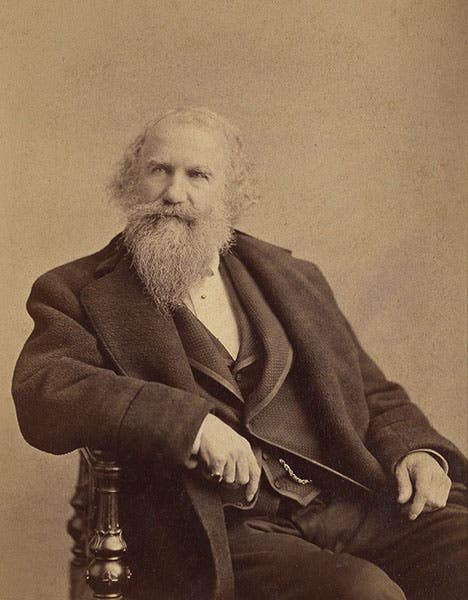

But an even older Mason locomotive is still in operating condition, owned by the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Museum in Baltimore. It wears number 25 and is now named, appropriately, the William Mason. It is a 4-4-0, a widely used format that is often called “American standard,” and was built in 1856. The William Mason has clearly been considerably refurbished, but supposedly no liberties were taken with Mason’s original design. It is normally on display in the museum, but every now and then, they roll it out and fire it up, as they did in 2012. This video shows two different locomotives in operation, so do not be misled; the first, no. 4, is of later vintage, but at the 1:32 mark, no. 25 shows up, painted green, and it steams along, forward and back, until the 3:27 mark. It reappears later, but those two minutes will probably suffice for most of you. What a handsome engine, 164 years old and counting! If you prefer your locomotives at rest (and I don’t know why anyone would), here is a still photo of no. 25 on display. Mason died in 1883, and the manufacture of Mason locomotives did not long survive him – the last one was built in 1889. Mason was buried in Mount Pleasant cemetery in Taunton, where his gravestone may still be seen. His portrait would suggest that he was well-suited to his status as an elder statesman for the locomotive manufacturing industry in the United States (second image). Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.