Scientist of the Day - Andrew Cowper Lawson

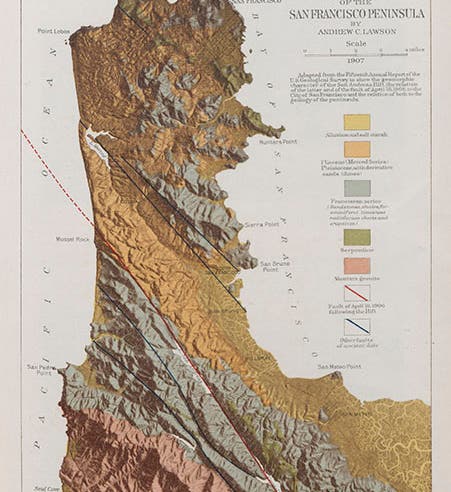

The great San Francisco Earthquake occurred on Apr. 18, 1906. The city was devastated, partly by damage from the quake itself, but mostly by the resulting fire (second image). For all the destruction and loss of life, the San Francisco earthquake marked a major milestone in our understanding of the causes of large earthquakes. A State Earthquake Investigation Commission was established immediately to examine the causes and circumstances of the disaster; it was chaired by geologist Andrew Cowper Lawson. Lawson was a professor at Berkeley; 11 years earlier, he had discovered a fault on the Bay Peninsula that he called the San Andreas Rift , named after either the lake it ran through or the valley that held the lake (first image). In the ensuing years, Lawson and many other geologists had established survey markers in central and southern California, which enabled geologists to measure distances between points and relative heights before and after the quake. With these geodetic measurements, Lawson and his commission established that the 1906 earthquake was caused by a slip along the San Andreas fault, which Lawson had originally thought to be a local fault.

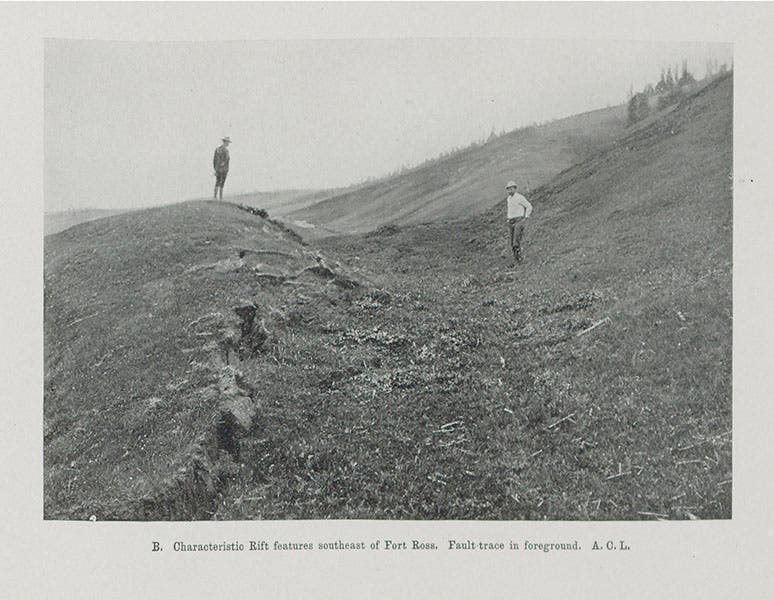

Lawson now found that the San Andreas Fault actually extends all the way down to the Gulf of California, and that during the quake, the rock on the west side of the fault had moved several feet north, compared to rock on the east side of the fault (fourth image).

Lawson could not have known, in 1908, that the San Andreas fault was a new kind of fault, a transform fault that constitutes a boundary between two tectonic plates, in this case the North American Plate, moving west, and the Pacific Plate, moving north. But otherwise the Commission report established for the first time what actually happens during a major seismic displacement like this one.

The report of the Earthquake Investigation Commisson was published in two volumes, 1908-1910 (fifth image). It is usually referred to as the Lawson Report. We have a set of the 2-volume Lawson report in the stacks of the Library, from which we reproduce four images.

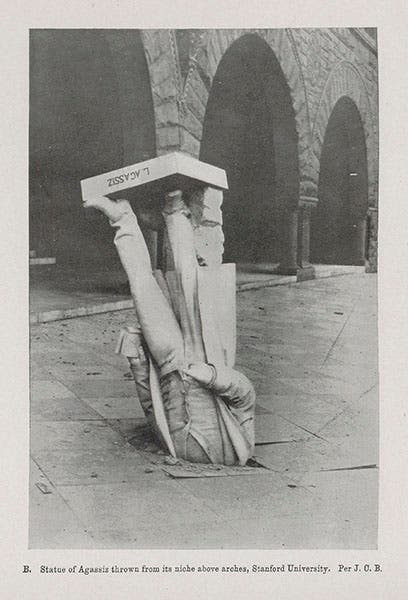

The photo of the fallen Louis Agassiz (fifth image), who toppled from his perch on Science Hall at Stanford University is quite renowned. So far as I can determine, the photo was first published here. It provoked the memorable remark, “Agassiz was great in the abstract, but not in the concrete."

The year after the great earthquake, Lawson commissioned the architect Bernard Maybeck to design build him an earthquake-proof concrete house in the Berkeley Hills, smack dab on the Hayward fault (sixth image). Maybeck did his job well. The house still stands.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![“Aurora Borealis,” hand-colored wood engraving by Josiah Wood Whymper, [Natural Phenomena], plate 2, 1846 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/0245ffcb-b70c-477c-8792-0a73ebd54eb2/Whymper%2011.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)