Scientist of the Day - Captain James Cook

James Cook, a British Royal Navy officer and explorer, was born Nov. 7, 1728. Cook came from a small town in North Yorkshire and earned his sailing chops in the port and shipbuilding city of Whitby, spending some years on colliers, the ships that shuttled back and forth to London bearing coal. Cook had little formal education, but he was a paragon of self-education, teaching himself trigonometry, geometry, astronomy, and navigation. He joined the Royal Navy in 1755 and worked his way up through the ranks, eventually impressing the Admiralty with his perseverance and proficiency at navigation, and his skill at chart-making, enough so that when the Admiralty decided to send out a ship to observe the transit of Venus in Tahiti in 1769 and then search for a southern continent while circumnavigating the globe, Cook was the choice to command. His ship was a bark built in Whitby, not unlike the colliers with which Cook was intimately familiar; it was renamed the Endeavour. He was promoted to lieutenant for the occasion, but not captain. In all, Cook would command three circumnavigations, each of them of prime importance for a variety of reasons. Today, we will limit our discussion to the initial voyage.

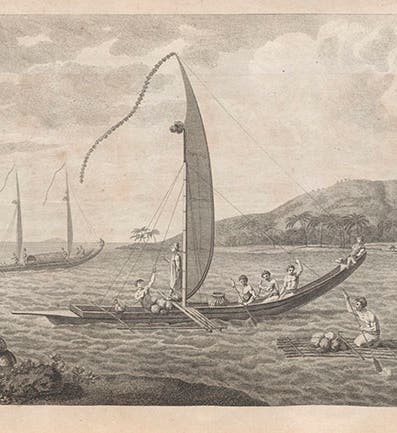

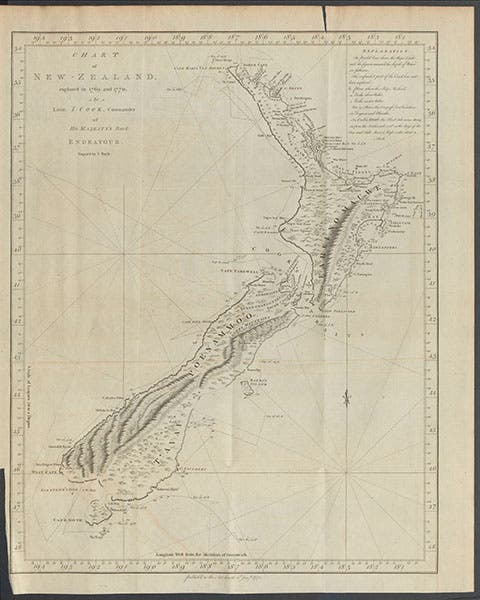

The first Cook voyage of 1768-71 was in a way co-sponsored by the Royal Society of London, who provided an astronomer and instructions for observing the transit, and more specifically, by a wealthy, young, paying passenger Joseph Banks, who put up the funds for the artists and naturalists and their supplies. Sometimes Banks' importance for the voyage is overplayed – he was a significant patron, and contributed greatly to the botanical success of the voyage, but he was not the commander. Cook may not have been in Banks’ league as a dinner companion or naturalist, but he could sail circles around just about anyone. He made it to Tahiti on time to observe the transit of Venus on June 3, 1769, and then crossed the Pacific to arrive at New Zealand in October 1769, a country that had been discovered by Tasman in 1642 and hardly visited since. Cook circumnavigated both North and South Island and produced a exceptionally accurate navigational map – the first map of the two islands – that would soon be published (third image).

Cook then took the Endeavour to New South Wales, the eastern part of Australia, and explored the entire coastline. Eventually he sailed through the dangerous Straits of Torres, thereby proving that Australia and New Guinea were not connected, and then brought his ship back home on May 12, 1771. Not a man lost his life to scurvy, the first time that had ever happened, because Cook had made sure that his crew was fed a proper diet, including foods that we now know were rich in vitamin C.

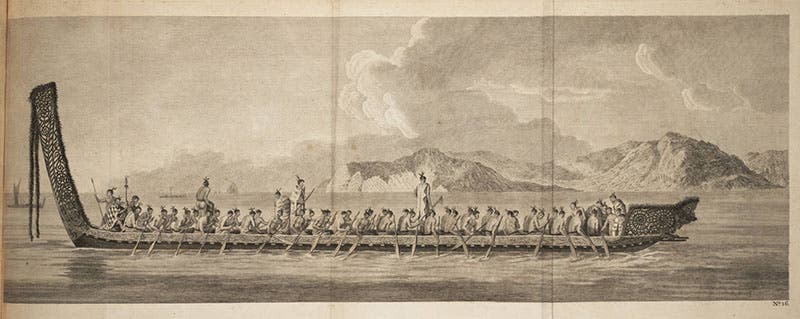

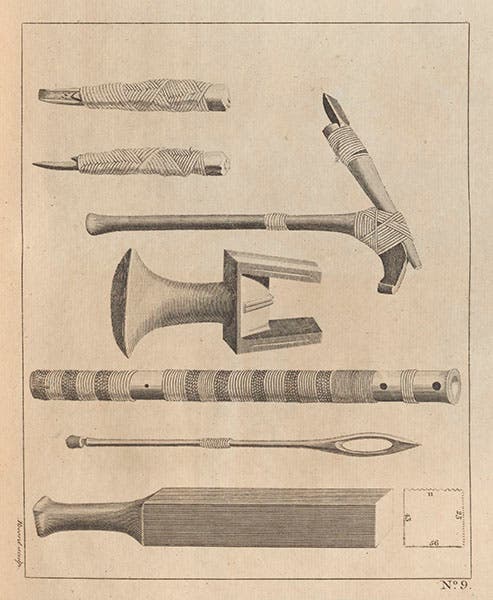

After the return, it was decided, probably by the Royal Society, that the rough-schooled Cook was not capable of writing a proper account of the voyage, so a young journeyman writer named John Hawkesworth was hired to turn Cook's logs and the artists’ sketches into a narrative, which was published in 1773 as An account of the voyages undertaken by the order of His present Majesty for making discoveries in the Southern Hemisphere, and which discussed 4 English voyages, Cook's being the last. It was pretty much of a disaster of an account, but a lesson was learned, and nearly every later narrative of a voyage would be written by the captain, including the narratives of Cook's second and third voyages. We have a copy of the first edition of Hawkesworth's Account, and if the text volumes are unreliable, the plate volume is a knockout. We show here 6 plates from that volume.

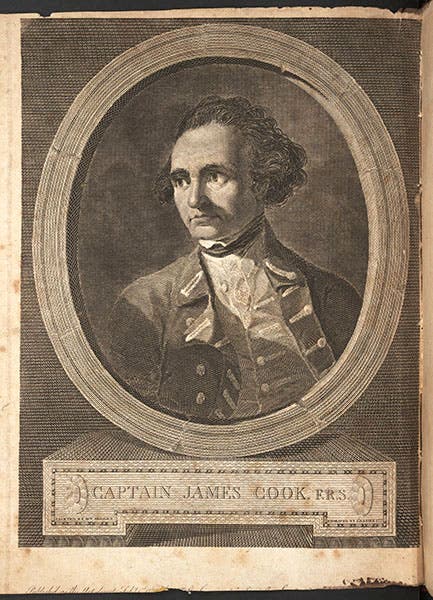

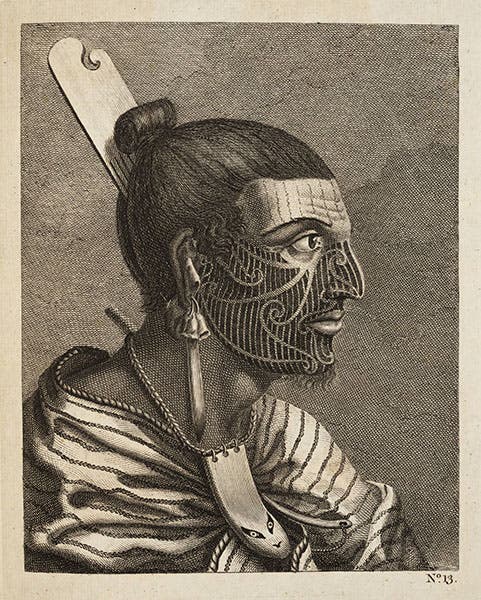

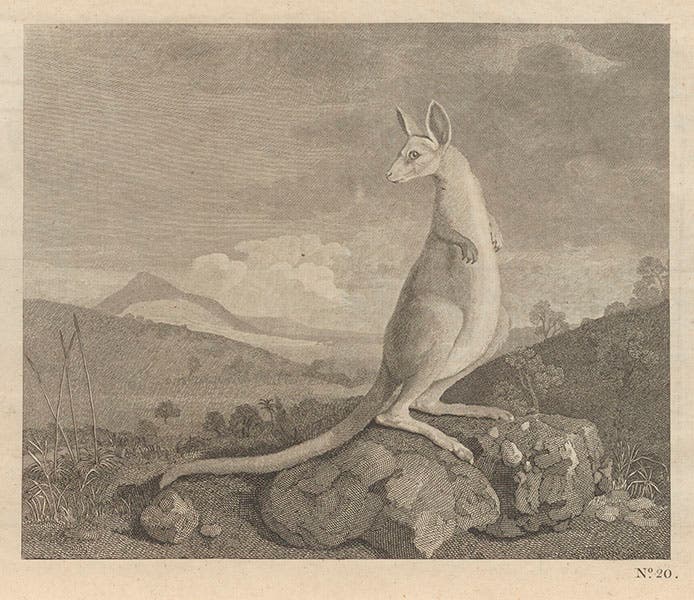

Perhaps the most famous plate, the one most often reproduced, is a close-up of the tattooed face of a Maori warrior, drawn by expedition artist Sydney Parkinson, who died shortly thereafter. The engraving of a kangaroo, also based on a Parkinson drawing, is quite popular as well (sixth image). Cook’s portrait (second image) comes from the narrative of the second voyage, where it serves as the frontispiece to volume 1. The engraving was based on a portrait sketch by Banks’ artist on the second voyage, William Hodges.

Cooks’ second voyage (1772-5) was significant because it explored further south than ever before (below the Antarctic circle) and because it used a chronometer, a copy of John Harrison's H4, to determine longitude. The third voyage (1776-80) discovered much of the north Pacific (including the Hawaiian Islands) and explored up through the Bering Strait, but also saw the death of Cook in Hawaii. We will discuss both of these voyages at a later opportunity.

There are over 100 memorials to Captain James Cook scattered around the world, in the form of busts, cairns, plaques, and statues. We show you the statue in his adopted home city of Whitby, where you can also find the Captain Cook Memorial Museum. (eighth image).

We displayed all three narratives of the three Cook voyages in a 2002 exhibition, Voyaging: Scientific Circumnavigations, 1679-1859, which is still available online.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.