Scientist of the Day - Carl Sagan

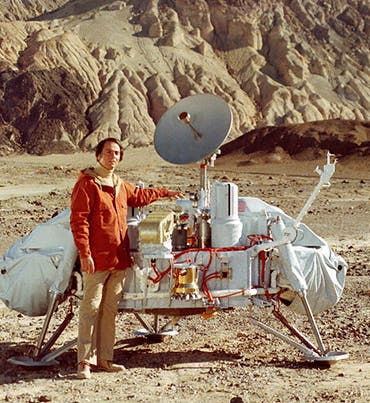

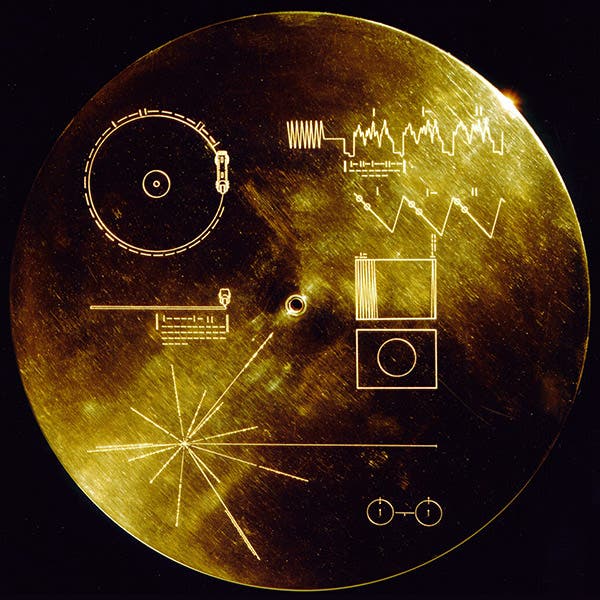

Carl Sagan, an American astronomer and public science spokesman, was born Nov. 9, 1934. Sagan was a planetary scientist at Cornell and an adviser to NASA during the early years of the space program (i.e., the 1960s and 70s). Another space program of sorts was being launched at the same time, the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence, or SETI, and Sagan was involved in that as well. He was adamantly resistant to the idea that ET has already visited earth ("extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence” is one of the more celebrated quotes from his later Cosmos series), but he was convinced that life, and probably intelligent life, existed elsewhere than Earth. So it is not surprising that Sagan was instrumental in persuading NASA to put messages intended for an extraterrestrial audience on the four space probes that would eventually leave the solar system: Pioneer 10 and 11, and Voyager 1 and 2. The Pioneer spacecraft departed first, and their messages were clearly afterthoughts, metal plaques bolted to the outside of the two spacecraft. But much more time and effort went into the Voyager messages, which consisted of sounds and images of earth, encoded upon gold-plated long-playing records (this was 1977, after all), and Sagan played a key role in generating enthusiasm for and selecting the contents of the Golden Record.

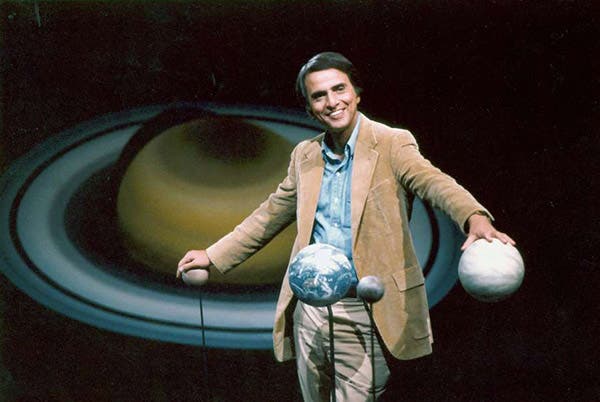

Sagan is best known for his PBS series, Cosmos: A Personal Voyage, which aired in the fall of 1980. It had been preceded by Kenneth Clark's Civilization series (1969), and Jacob Bronowski’s The Ascent of Man (1973), both absolutely splendid, but Cosmos still managed to set a new standard for popular science television that has never been surpassed, even in the CGI age in which we live. I watched the entire series as it was aired, week by week for three months, and I was not so much enthralled as incredibly impressed, since I knew how hard it is to maintain a consistent and convincing vision through a 13-part series that covers the entire universe, and how difficult it is to get all the facts right, especially when making frequent forays into the history of science, which was not really Sagan's domain.

But Sagan did astonishingly well, much better than his successors, because Sagan had excellent historical consultants to whom he was willing to listen. And he did have an eager and friendly manner about him, and a silver tongue, and a way with words, which made him a pleasure to listen to. You can find all 13 episodes of Cosmos on YouTube, but be advised that these are not the original programs--many of the images have been replaced and the graphics updated (which may not be a bad thing for a modern audience, since graphics were primitive in 1980, and planets such as Uranus and Neptune had not yet been imaged when Cosmos originally came out).

Sagan’s book Contact (1985), made into a successful motion picture (1997), might be the subject of a future anniversary.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.