Scientist of the Day - Daniel Solander

Daniel Solander, a Swedist botanist, was born Feb. 19, 1733. Solander trained under the great Carl Linnaeus in Uppsala and moved to England in 1760, thereby becoming one of the many Linnaean "apostles" who helped put Linnaean taxonomy into practice. Solander began working for the British Museum, distinguishing himself well enough so that when Captain Cook's first voyage was being outfitted in 1768, Solander was asked by Joseph Banks to join the team of naturalists on board the Endeavor. Solander agreed, and as a result, he became the first Swede to set foot on the Australian continent, and indeed the first Swede to circumnavigate the globe, when the Endeavour returned to England in 1771. Cook must have appreciated the services of Banks and Solander, for he named the large inlet where they first landed, just south of modern Sydney, "Botanists Bay" (which he later changed to "Botany Bay”), and someone, probably Cook, named the point just below the bay, “Cape Solander.”

There is a fine painting by William Parry in the National Portrait Gallery in London (second image) that depicts Solander (at far right), Banks (center); and (at left) the illustrious Omai, a Tahitian brought back to London by Cook. The painting is a bit misleading, since Omai came back on Cook’s second voyage of 1772-75, a voyage in which Banks and Solander did not participate. Nevertheless, the painting provides the only good portrait of Solander that we have, excepting a charming cameo fashioned by the pottery firm of Josiah Wedgwood I (first image).

Getting back to Cook’s first voyage of 1768-71, Solander’s principal activity was gathering plants for Banks’ growing herbarium, which Solander did with both acumen and gusto. Upon their return, Banks commissioned engravings of hundreds of plants, mostly Australian specimens, intending to publish them in due course. As sometimes happens, circumstances intervened, and publication was delayed for nearly 200 years! However, from 1980 to 1990, the 743 colored engravings were finally issued, and Solander’s prodigious collecting efforts finally bore fruit. We have the complete set of the Banks Florilegium in our History of Science collection, housed in our vault in 34 large clamshell boxes. Here is part of the set owned by Kew Gardens in London; our set looks very much the same, except that our rolling folio shelves are faced with steel, not rosewood.

And speaking of clamshell boxes, one of Solander's other claims to fame is that he invented the clamshell box – in fact, it is usually called a Solander box. He got the idea while working in the British Museum, where he needed some safe way to store both drawings and dried plants. Below (fifth image) is an example of a Solander box. It has an attached cover, is easy to open and close, and is stiff enough to provide protection for objects inside, whether leaves of paper or leaves of plants. We have quite a few Solander boxes protecting various rare books in our vault. One book so sheltered is the De revolutionibus (1543) of Nicholas Copernicus, which resides in a bright blue Solander box. That seems quite fitting, since Copernicus, born in 1473, is also celebrating a birthday today. Or he would be, if he were 548 years old.

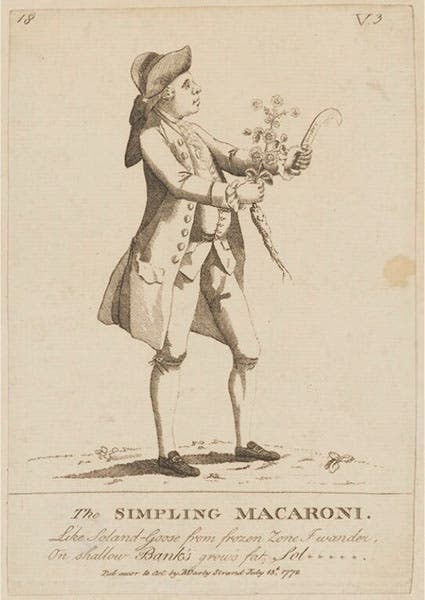

Finally, there is an odd caricature of Solander in the National Portrait Gallery, with a surprisingly harsh verse below:

The Simpling Macaroni

Like Soland Goose from frozen zone I wander

On shallow Banks grows fat, Sol*****

I do not know what provoked this and its mate (a similar caricature of Banks), since by most accounts, Solander was amiable and sociable and a popular figure in London society. How the two got lumped in with the androgynous macaronis, I do not know.

Solander became Banks’ secretary and librarian and for nine years was keeper of the natural history collections in the British Museum, until his death in 1782.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.