Textbook Dinosaurs, 1859

Natural history encyclopedias were very popular in the nineteenth century, but they rarely included extinct animals. Samuel Goodrich's Illustrated Natural History of 1859 provided an appealing departure from the norm. Midway through the chapter on reptiles, after a discussion of the common chameleon, we are suddenly presented with a short section on "fossil lizards", illustrated with four large wood engravings on succeeding pages. We reproduce here the second of these cuts, Hylaeosaurus. The other illustrations show Iguanodon, Megalosaurus, and a collection of marine reptiles such as Ichthyosaurus. All of the illustrations were copied from the Crystal Palace restorations, as Goodrich attests in a note.

Hylaeosaurus was discovered by Gideon Mantell in 1832 and was first announced in his Geology of the Southeast of England, 1833. It was one of Richard Owen's original three dinosaurs, and in restoration stood prominently on the Crystal Palace grounds.

Another very popular work that illustrated the dinosaurs in their habitats was Louis Figuier's World Before the Deluge. The dinosaurs in Figuier are not only more dynamic, but they are less indebted to the Hawkins' restorations.

Megalosaurus and Iguanodon, 1859

Besides the Hylaeosaurus, the other two dinosaurs depicted in Goodrich's encyclopedia are the Iguanodon (right), and the Megalosaurus (below). Both illustrations were direct copies of the life-size sculptures designed by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins and erected in Sydenham Park in 1854 (see item 5).

There is also a considerable resemblance between Goodrich's Megalosaurus and the reconstructed drawing by Richard Owen, also made in 1854.

The Discovery of Hylaeosaurus, 1833

The third dinosaur to be recognized as such was discovered by Gideon Mantell in Tilgate Forest in 1832. In The Geology of the South-east of England (1833), Mantell said of his discovery:

"I venture to suggest the propriety of referring it to a new genus of saurians...and I propose to distinguish it by the name of Hylaeosaurus."

In a footnote, he explained that the name means "Wealden Lizard." Mantell continues:

"The original animal in all probability differed as much in its external form as in its skeleton, from known species; we are certain that it was covered with scales, and there appears every reason to conclude that either its back was armed with a formidable row of spines, constituting a dermal fringe, or that its tail possessed the same appendage... the specific name of armatus, in either case, would not be inappropriate."

Mantell estimated the size of the Hylaeosaurus at no more than 25 feet, which was half the size of Iguanodon and Megalosaurus, in his estimation.

Mantell published another illustration of the Hylaeosaurus slab in the fourth edition of his later book, The Wonders of Geology (1840). Interestingly, it was a different image, completely redrawn from this one.

Two Versions of Hylaeosaurus, 1833 and 1840

The image at the bottom left shows Gideon Mantell's Hylaeosaurus fossil in its matrix, as he pictured it in 1833, in The Geology of the South-east of England. The image on the right shows its depiction as published in 1840 in the fourth edition of The Wonders of Geology. Both are lithographs, but they are quite different in appearance, which shows that the eye of the artist was a not insignificant intermediary between the actual fossil and the printed image.

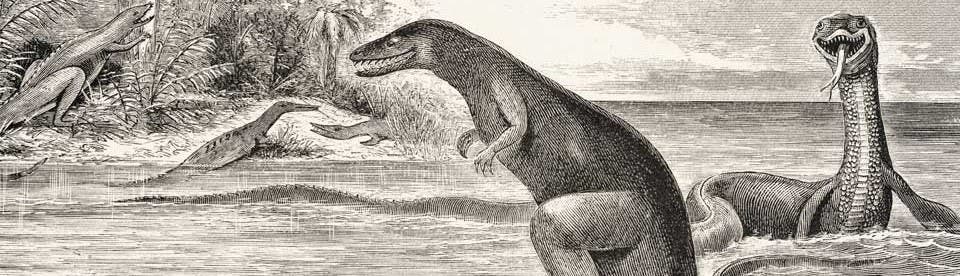

Figuier's World Before the Deluge, 1867

Louis Figuier's La terre avant le deluge was first published in 1863, and it became immensely popular and was often reissued and translated; we have an 1867 English translation. Figuier included a unique series of restorations of different periods of the earth's past, which were drawn by Edouard Riou. The illustration below resurrects two animals of the Weald: an Iguanodon and a Megalosaurus. Unlike the reconstructions of Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, these two dinosaurs are warring with one another in a quite ferocious manner.

Notice that although the effect here is quite different from the tranquil scenes in Goodrich's Illustrated Natural History, the pose of the Megalosaurus is identical in both cases.