Scientist of the Day - Flavio Biondo

Flavio Biondo, an Italian humanist, died June 4, 1463, at the age of about 71; his exact date of birth is unknown. Biondo is regarded in many quarters as the father of archaeology. Biondo was born in 1392 in Forli in the Romagna region of north Italy, where, a century later, Caterina Sforza would rule and vent her wrath upon those foolish enough to try to remove her. Biondo moved to Rome in 1433 and eventually became the Papal Secretary to Eugene IV and three more popes after him. When Biondo came to Rome, it was a wasteland, a far cry from the glory days of the Republic and the early Empire. The flight of the papacy to Avignon (1309-1376) had nearly bankrupted the city, and the further schism with multiple simultaneous popes, not resolved until 1417, had produced even more decay, both physical and moral. The Forum that was the glory of ancient Rome was a pasture, the Capitoline hill was denuded of structures. Ruins lay all about, but no one knew what they were, and worse, no one cared.

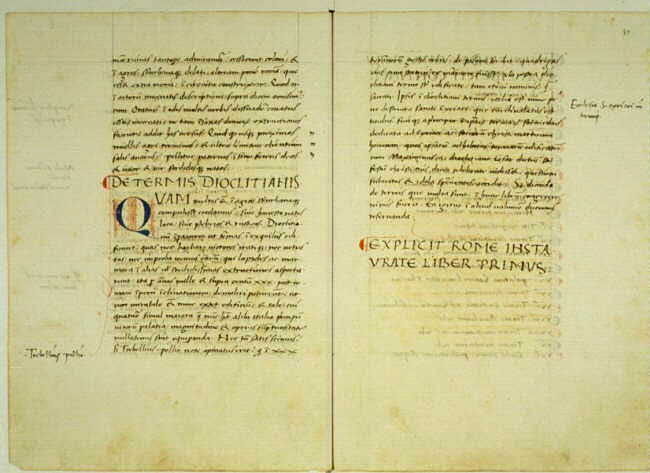

Biondo read every ancient source he could find (he was a humanist, after all, and that is what humanists did), and he began to try to match up the place descriptions in the works of Pliny and Livy with the arches, columns, and stones he found scattered around Rome. Between 1442 and 1446, he compiled a guidebook to the ruins of Rome called Roma instaurata (Rome restored). Printing had not been invented yet, but copies of the manuscript circulated widely. Nearly everyone with antiquarian interests who came to Rome brought or bought a copy of Biondo's guide. Because of Biondo, when statuary was recovered, it was preserved and cherished, not discarded as some pagan detritus. When contemporaries found building stones or foundations, they began to follow Biondo's lead and search carefully for identifying inscriptions. Later institutions, such as the Belvedere Gardens, where you could find the Apollo Belvedere, the Medici Venus, and the Belvedere torso, would never have been created, had Biondo and his contemporaries not shown us that the past was worth being recovered and restored.

When the Vatican Library sent a selection of its books and manuscripts to the Library of Congress in 1993, for exhibition, a manuscript of Biondo’s Roma instaurate was included (second image, above). The exhibition is still available online – here is the entry for Biondo. The title of the exhibition – Rome Reborn – was inspired by the title of Biondo’s book.

We do not have much in the way of imagery for Biondo, but the images we do have are good ones. We have a portrait (first image). It is not contemporary, but it is close, and it was engraved by the great Frankfurt engraver and publisher Theodor de Bry. It was published in Jean-Jacques Boissard’s Icones quinquaginta virorum illustrium (1597-99; the title hints at 50 portraits, but there are actually 200 in all four volumes). We acquired our set in 1996 from New York City bookseller Jonathan Hill.

Biondo's funerary slab is also available to view, should you happen to be in Rome, or if not, on Wikimedia commons (third image, above). You will note from both his portrait and his memorial stone that he was commonly known as Flavio Biondo Forliviensi – Flavio Biondo from Forli. Biondo was buried in the church of Santa Maria in Aracoeli (St. Mary of the Altar of Heaven), at the very top of the Capitoline Hill, where his spirit, perhaps, can survey the entire expanse of the Rome that he brought back to life (fourth image, below).

We don’t often write about Renaissance archaeology, but some years ago we posted an entry on Maerten van Heemskerck, a Dutchman who came to Rome a century after Biondo, with many of the same intentions, to preserve the antiquities of ancient Rome, but this time on paper. We showed there his sketches of the Forum, the Belvedere torso, and himself, standing before the Colosseum.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.