Scientist of the Day - Georg Christoph Lichtenberg

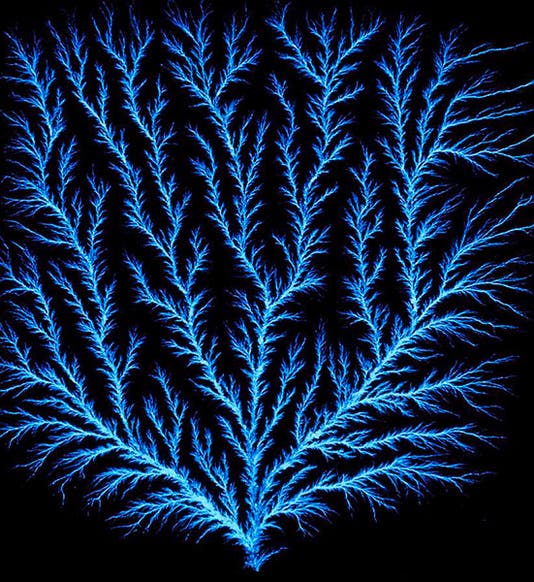

Georg Christoph Lichtenberg, a German physicist, was born July 1, 1742. Lichtenberg was professor of physics at Göttingen for his entire working life. He was especially interested in electrical experiments, in that age of Franklin and Galvani, and he built a large electrostatic generator, with which he discovered what are now called "Lichtenberg figures" – frilly, tree-like patterns that form when high-voltage sparks pass through certain dielectric materials such as wood and plastic. He initially noticed them in patterns of dust that settled on electrified bodies, but nowadays it is more popular to form the figures by zapping clear acrylic blocks with millions of volts. We see a still of a Lichtenberg figure above (first image), but it is much more fun to watch them being formed.

Georg Lichtenberg, bronze sculpture, in a Göttingen square (staedte-fotos.de)

Lichtenberg also edited the papers of Tobias Mayer, a brilliant young Göttingen astronomer who died in 1762 at the age of 39 before he had published hardly anything. Lichtenberg put together an Opera inedita from Mayer’s papers, publishing it in 1775, and giving the world Mayer's excellent moon map, which we displayed in our long-ago exhibition, The Face of the Moon, as well as a lovely and original color chart of Mayer’s design (third image). Had Lichtenberg not taken time away from his busy electrical agenda to publish Mayer’s papers, Mayer’s scientific legacy, which is considerable, would have been lost.

But perhaps Lichtenberg's most notable contribution to letters was a large collection of aphorisms. During his entire life, he would jot down observations in what he called his Sudelbücher, or “Waste books”, making a repository that he might have later mined for literary purposes, but which he declined to so use. None of his aphorisms had been published when he died in 1799. But when they were discovered long after his death and edited and printed, they became immediately popular, so that Lichtenberg is best known in Germany today as a wit and a philosopher, and not as a scientist. You can buy your own copy and wade through all 1000+ aphorisms on your own, but if you just want a taste, I have culled for you some of my favorites – a few that have nothing to do with science, and one that does. We live in a world in which one fool can make many fools, but one wise man only a few wise ones. A book is a mirror: if an ape looks into it, an apostle is hardly likely to look out. When a book and a head collide and a hollow sound is heard, must it always have come from the book? And one that I hope my friends in the Netherlands will excuse: The ass seems to me like the horse translated into Dutch. This next aphorism justifies Lichtenberg’s inclusion in our series – it is an observation about Nature, which must be viewed against the claims of Bacon, Galileo, and Boyle that they had learned to read the Book of Nature: In Nature we find, not words, but only the initial letters of words, and if we then attempt to read them, we find that the new so-called words, are again merely the initial letters of other words. Touché, Galileo!

They are proud of Lichtenberg in Göttingen, and there are at least two bronze statues of this philosopher-son in the city’s streets and squares. You will notice that the statues are small, for Lichtenberg was not only physically frail, he was a hunchback. One statue stands in a public square; it either is portable or has been duplicated, for I have seen it in different locations (second image). Lichtenberg holds a globe with the symbols “+/-“ and “-/+” engraved upon it. I do not know what that is intended to represent – if it is polarity, that would be anachronistic. Whatever it means, the globe is obviously considered good luck or good fortune, for it has been rubbed to a high polish (fifth image).

The other sculpture is more charming, with a bronze Lichtenberg expostulating from a bench about an open bronze book that is just another bench away (sixth image). Perhaps another aphorism is coming our way. Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.