Scientist of the Day - George Adams, Jr.

George Adams, Jr., an English instrument maker and author, died Aug. 14, 1795; he was born in 1750, with no known birthday. His father, George senior, was also an instrument maker, with a shop at Tycho Brahe's Head on Fleet Street in London; George Jr. took over the business when his father died in 1773. George Jr. was unusual for an artisan in that he wrote books, not so much about his instruments as what you could do with them. He wrote books on electricity (1784), microscopy (1787), surveying (1791), and even natural philosophy (1794), all of which we have in our history of science collection. We thought we would feature today his Essays on the Microscope, because it is our most recent Adams acquisition, purchased several years ago from the San Francisco bookseller, Jeremy Norman. It is a handsome set, with a thick quarto text volume and an oblong folio atlas with 31 plates, a number of which we reproduce within this post.

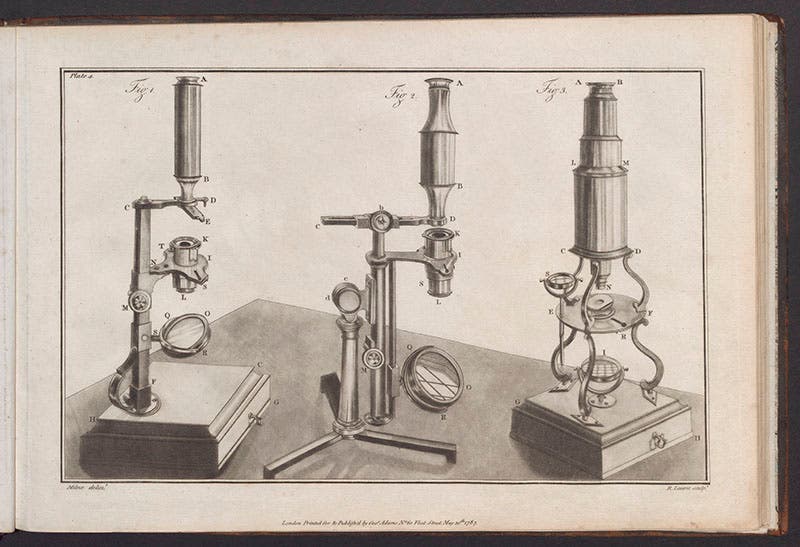

The first 9 plates depict microscopes or details of microscopes – books like this did double duty as trade catalogues. The plate we reproduce shows three compound microscopes available from Adams' workshop (second image).

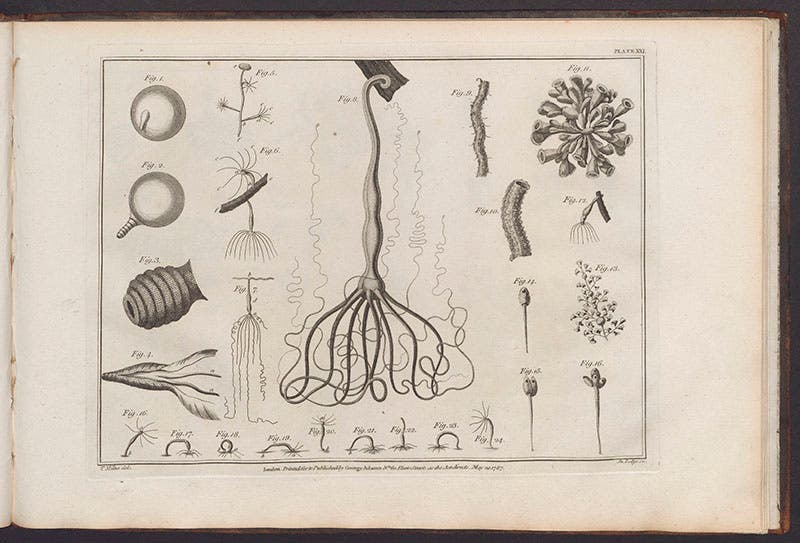

The last 22 plates offer up objects that you could see with your Adams microscope. One of the most popular subjects for microscopic examination in the late 18th century was the hydra, which Abraham Trembley had made famous when he showed that you could cut a hydra into pieces that would regenerate into complete organisms. We see here one of four plates from Adams' book that depict hydra (third image).

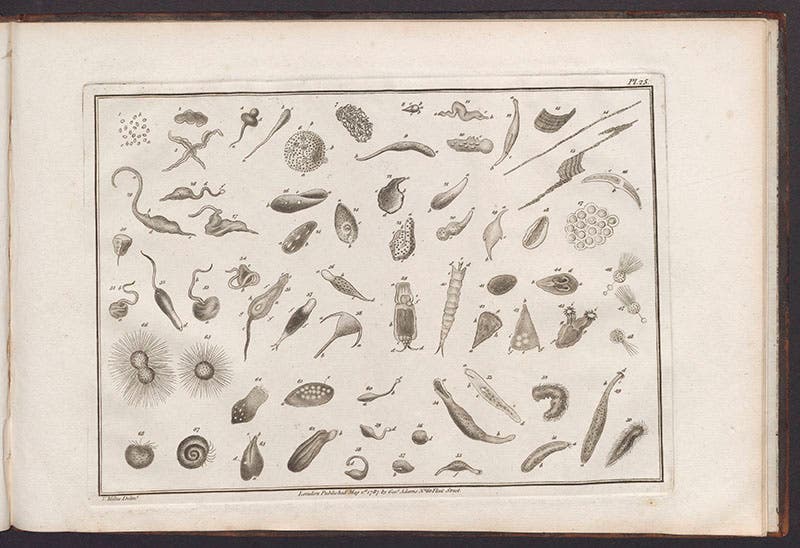

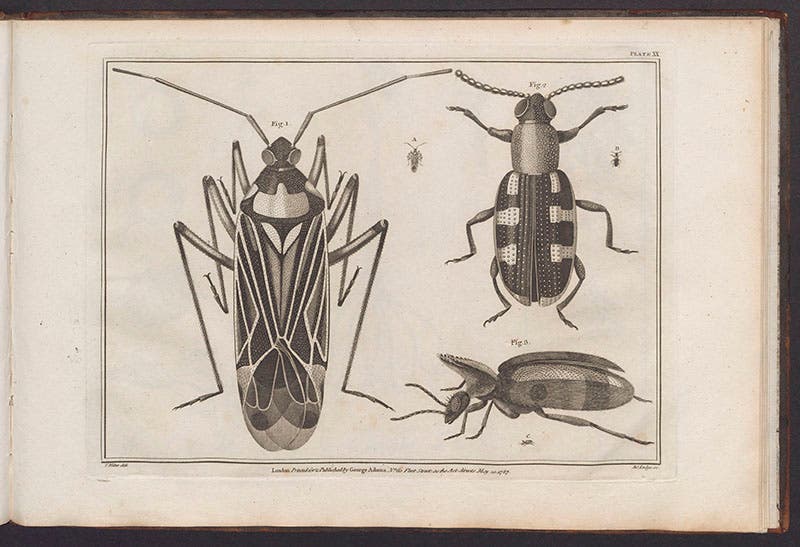

The other most popular objects for microscopists were "animalcules," to use the name than Leeuwenhoek gave to protozoa. Adams called them "animalcula infusoria", and he devoted 70 pages of his text and three plates to these tiny organisms (fourth image). We have not attempted to sort these out here, but Adams does in his commentary, calling them all by name. There are also several plates of insects, just to carry on the tradition of Robert Hooke; we show here one that depicts three coleoptera (fifth image).

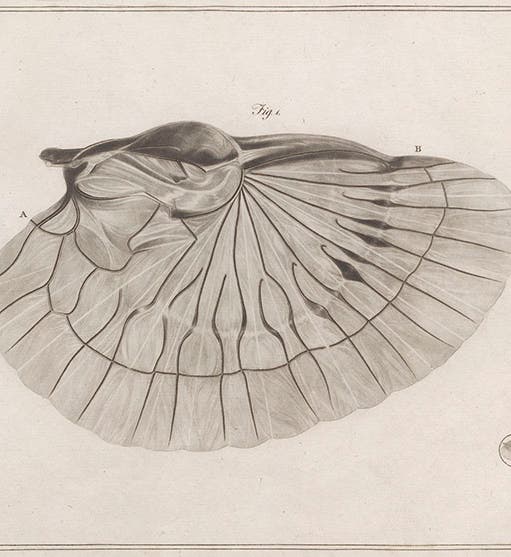

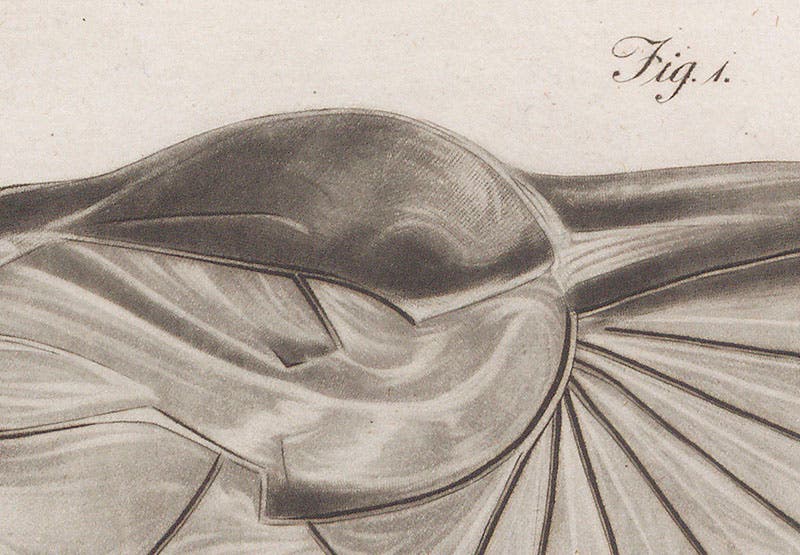

The most striking plate in the atlas is the one with which we began (first image). Most people would never guess what it represents - I certainly didn't - as it depicts the unfolded wing of an earwig. Equally striking is the medium of the image; what looks like a soft pencil sketch is actually a mezzotint, burnished so extensively that one would never guess this without a magnifying glass. We show you a detail (sixth image, just above) to bring out the marks of the mezzotint rocker. Quite a number of the plates in the volume are mezzotints, including our second image of the three microscopes.

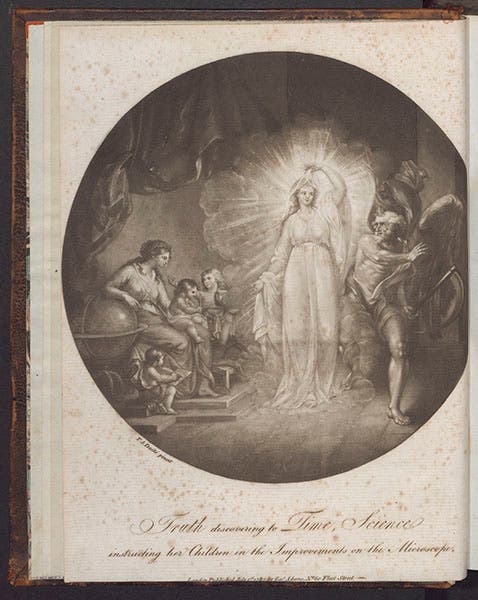

The text volume is unillustrated, as text volumes should be, but it does have an attractive frontispiece, depicting Truth being unveiled by Time, which we couldn't resist including here (seventh image). It is more obviously a mezzotint.

His popularity as a writer notwithstanding, Adams was first and foremost an instrument maker, and many of the instruments constructed at Tycho Brahe's Head survive today in museums and private collections. We show you one, "microscope no. 6", that is in the Golub Collection at the University of California, Berkeley (eighth image). It is the center microscope illustrated in our second image. Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.