Scientist of the Day - Giovanni Battista Ferrari

Giovanni Battista Ferrari, an Italian Jesuit gardener, of all things, died Feb. 1, 1655. I say "of all things", because Jesuit scientists usually concentrated on astronomy, optics, pneumatics – the physical and mathematical sciences – and it is rare to find a Jesuit fooling around with pots and sphagnum moss. Ferrari took care of the Hortus Barberini, the garden of Cardinal Barberini (the Pope's nephew) in Rome, and apparently hob-nobbed with the rich and famous. Ferrari published two botanical books that are quite lovely. The first, De florum cultura (1633), we have in our History of Science Collection, and we will feature it today. It is divided into four parts, with each section introduced by a frontispiece by a highly-regarded artist and engraver, such as Pietro de Cortona and Claude Mellan. Our images are drawn mostly from part 2, which discusses different garden species, and part 4, which treats of exotic flora that were found only in the finest Italian gardens, such as the Hortus Barberini.

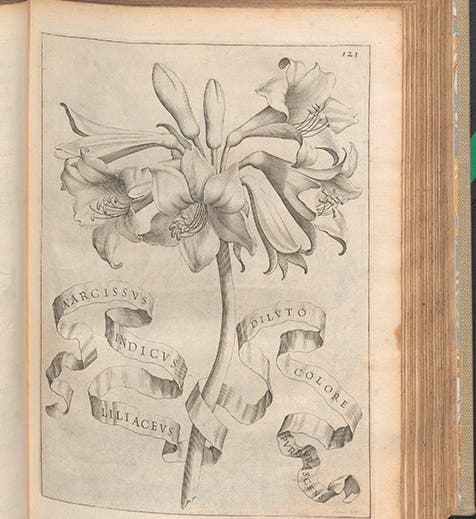

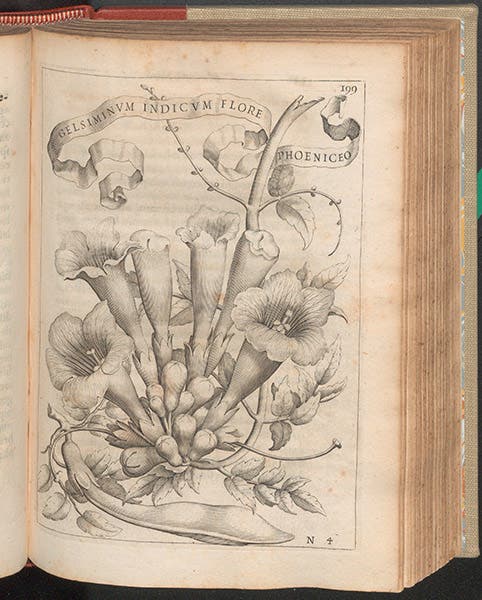

Our first image, the caption tells us, is a Narcissus indicus – we would call it a Belladonna lily. Some copies of this book are hand-colored, but ours is not, which in some ways is better, if you want to appreciate the variety of engraving techniques. The second image shows us a Gelsiminum indicus, a trumpet vine.

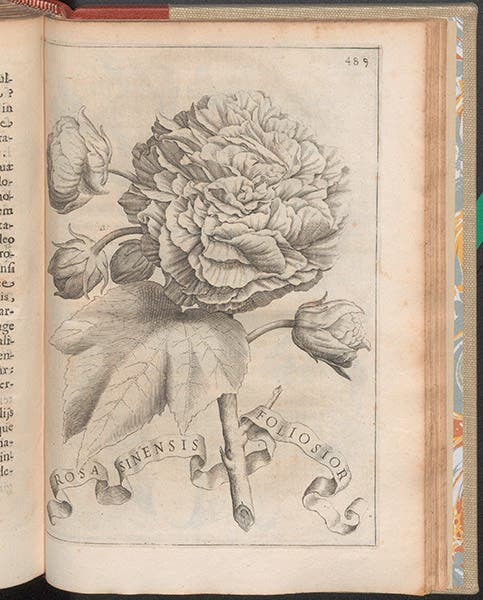

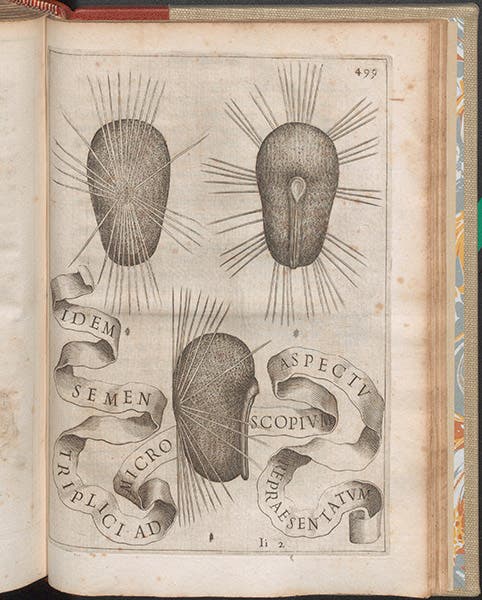

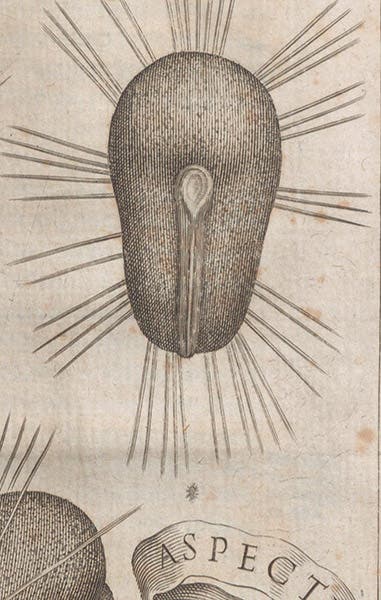

There are several engravings in the book that depict different varieties of Rosa sinensis, the Chinese rose, or hibiscus, which was apparently the showpiece of the Barberini gardens. We see one of these in our third image. It certainly seems more attractive than our fourth image, which shows three prickly seeds of the Chinese rose.

But the fourth image just above is historically the most significant engraving in the book. You can probably guess the importance if you peruse the caption, even if you do not read Latin, and come to the word “microscopium.” These three seeds have been drawn using a microscope, a new instrument invented by Galileo just 18 years earlier and employed only once before to enlarge an image in a printed book (you can read about the “once before” in our post on Francesco Stelluti). In our fifth image, we show a detail of one of the magnified seeds, and just below, looking like a tiny spider on the page, is the seed at natural size. Scientific illustration of the very small is going to change radically very soon, with the work of Robert Hooke and Antoni van Leeuwenhoek in the 1660s, and it all starts right here.

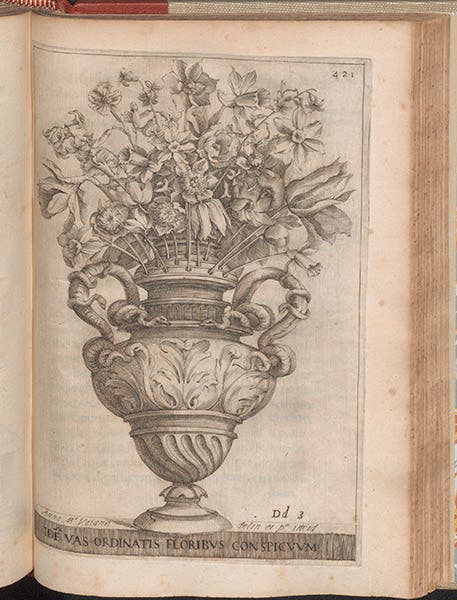

There is one other engraving that is significant in quite a different way. Our sixth image is a floral arrangement, of which there are several in Ferrari’s book. But this one is signed “Anna Maria Vaiana.” Anna Vaiana is the first woman copper-plate engraver known by name, and if there is an earlier plate signed by her in any scientific book, I am not aware of it. So that makes De florum cultura a doubly special florilegium.

Ferrari published a second botanical book, Hesperides sive de malorum aureorum (1646), with the focus on citrus fruits, the first ever such book, with many engravings of lemons, limes, and oranges, again by the country’s finest artists. It is purportedly even more magnificent than De florum cultura, but we do not own it. Perhaps in a few years, when Ferrari’s birthday rolls around on some other Feb. 1, we will have it in our collections and can devote another post to that rarest of creatures, the Jesuit botanist.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.