Scientist of the Day - Guarino Guarini

Guarino Guarini was born Jan. 17, 1634 in Modena, Italy and lived to age 59. He was the most prominent architect of his time in Northern Italy, creating an architecture intended to inflame spiritual passions, which was a goal of the Catholic Counter-reformation esthetic culture of the time. And beyond his architectural work, he was a prominent engineer, mathematician, philosopher, and cosmologist. He advocated for the integration of art and science, to create the richest emotional forms of buildings. His architectural approach may best be understood in this quote from him: The magic of wondrous mathematicians shines brightly in the marvelous and truly regal architecture.

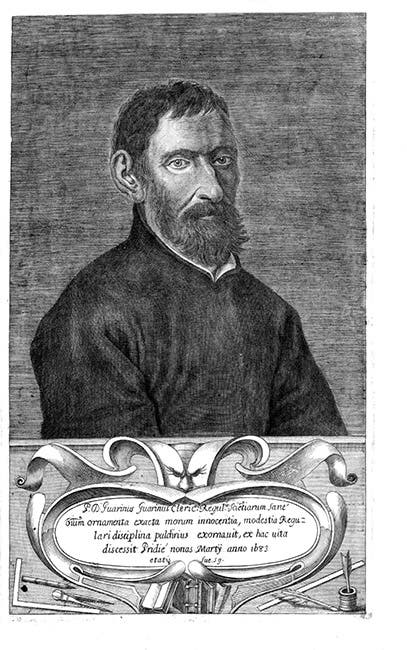

Our first image shows the interior of the dome of his magnum opus, the Chapel of the Holy Shroud (Santa Sindone) in Turin, Italy, to give some reality to his words. I shot this photograph in 2019 just after its reopening, after being closed for 28 years due to a disastrous fire. The dome shows the nested hexagons of dozens of clerestory windows providing indirect, diaphanous, “heavenly” light. And in a closer shot (second image, below), one can see each horizontal clerestory more clearly as they spin around the dome and rise in each subsequent nest of hexagons, culminating in the 12-pointed terminus of “God’s heaven”.

Detail of dome interior, Chapel of the Holy Shroud, Turin, designed by Guarino Guarini, 1668-94 (photo by the author)

Guarini’s early life is mostly lost to history, but his intensely full professional life can be best understood by four facts: his devoutly religious family setting; his exile from his homeland; his place in the Reformation and Counter-Reformation; and his resulting Baroque style.

He came from a deeply religious Catholic family in Modena (Northern Italy). He and his four brothers all became Theatine priests, which presumably ended the family’s lineage, given the Catholic clerical vow of celibacy. At least in the case of Guarini, his esthetic legacy has lived on in his remarkable buildings. Despite Guarini’s priesthood, there is no evidence he was particularly religious, since he focused all his energies on his design projects and his many down-to-earth books on mathematics, construction, engineering and architecture.

The Theatines were one of the new Orders, created to reinvigorate the failing and corrupt Church after the Protestant Reformation. Because it was new, the Theatines attracted financial support and had major building programs throughout Italy and Europe in such areas as Portugal, Bohemia, Paris, and Sicily. This wide geographical program was to be a great boon to Guarini’s career.

After his higher education in Rome, the Theatines’ headquarters, he returned to Modena. He was a rising star, since by age 30 he had already been named a professor of philosophy and was involved in various major construction projects around Modena. His success was such that the Order decided to make him the head of the Theatines in that region (the Dukedom of Modena). The Duke’s son (who was the current de facto ruler), for unknown reasons, objected to Guarini being appointed to that high position and banished him from the region.

Guarini’s exile could be characterized as a sweet lemon, since it meant that he became a wandering architect, taking advantage of many design opportunities across Europe, backed by a powerful and wealthy organization. This exile also thrust him into various intellectual arenas around Europe, where he could expand his intellectual interests. Though most of the details of his travels are lost, he ended up spending some years in Sicily, in Lisbon, in Paris, and ultimately in Turin. The self-inflicted loss by the Dukes of Modena of exiling Guarini was the gain of the local Theatine leaders in various countries; it was also a gain for the local ruling families who hired him to design and manage many architectural projects in these different cities.

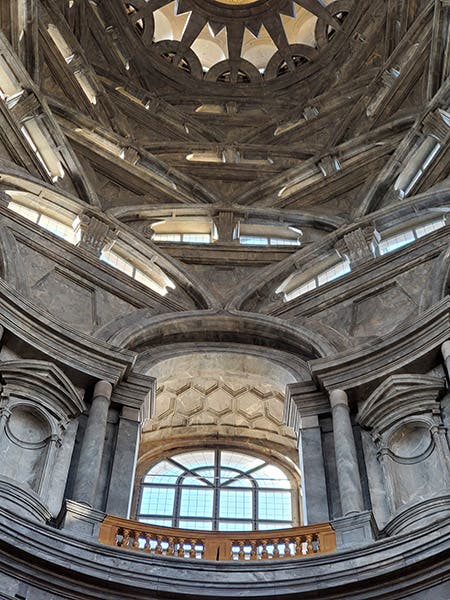

Renovation in progress, Chapel of the Holy Shroud, Turin (photo in possession of the author)

In the midst of his wide-spread architectural and engineering practice, he kept up a steady outpouring of books. One important publication was his Euclides auductus et methodicus mathematicaque universalis (1671), which covered not only geometry but the new field of descriptive geometry: the translation of 3D objects into 2D projections. He was aware of the foundational work by his contemporary in France: Girard Desargues, a mathematician and part-time architect. This was a century before the other main founder of descriptive geometry: Gaspard Monge. Guarini applied these concepts of geometry to build his complex domes. I followed with great interest the decades-long rebuilding of the dome after the year of fire, and read essays by various Italian specialists who were puzzling over how Guarini actually accomplished his complex structural geometry. In 2019, I met one of the main restorers of the dome, who provided me with a group of in-progress photos showing the damage and the restoration. Our third image gives a sense of scale of how large this dome is.

Unfortunately, Guarini’s cosmological/astronomical legacy was not as lasting as his mathematical and architectural legacy, since his first book (on general natural philosophy) and his last book (on the heavens) rejected the Copernican and Galilean view of the universe, in favor of the still prominent but failing geocentric theory. This latter book, Cælestis mathematicae (1683), is in the Linda Hall Library collections.

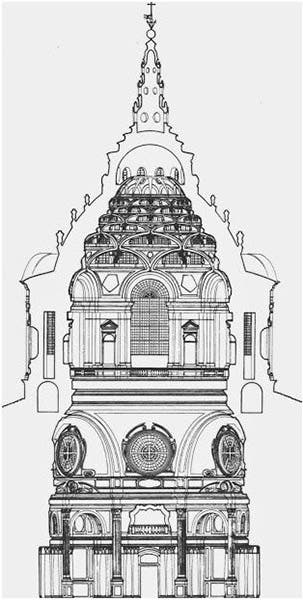

Section of the Chapel of the Holy Shroud, Turin (matematica.unibocconi.it)

Guarini’s architectural work is viewed by art scholars as part of the movement of artists and architects who advanced the efforts of the Catholic Church to re-convert followers who had left the Church for various forms of Protestantism during the Reformation. This Counter-Reformation (dominant from the mid-16th to the mid-17th centuries) was devoted, artistically, to imbuing painting, sculpture, architecture and other arts with a new passion, a new way for the faithful to directly grasp the wonder of God and his heaven. Guarini’s work exploited complex structural systems that created forms that were filled with both rhythm and movement, evoking in the viewer a connection to a spiritually higher plane of existence. His dome for the Chapel of the Holy Shroud, in the images shown above, and then in section (image 5, just above), was a tour-de-force, creating a sense of being drawn upward into an ethereal region of existence – to infinity Though experiencing architecture requires physically being in the spaces, this section will give some sense of the spiritual/physical uplift one can feel standing in this space.

Dome interior, Church of San Lorenzo, Turin, designed by Guarino Guarini, 1668-87 (photo by the author)

In his church of San Lorenzo, also in Turin, shown just above, Guarini emphasizes the structural method, by having the leaping arches hexagonally spanning the space, with large windows and various geometric skylights and clerestories visually connecting the viewer to the heavens, and evoking a sense of marvel at the multi-layered perfect symmetry of the hexagonal geometry of the space.

There is only one known portrait of Guarini, at age 57, suggesting he was an alert, austere man (sixth image).

The structural baroque style he pioneered is radically different from the later eras of baroque and rococo encrusted-ornamental styles. Typically, such styles were all surface effects, without any attention to structural engineering and geometry. In this writer’s experience, it matters not that some of his best work had a religious motivation related to what one was to expect after dying and going to heaven, since his theme can easily be experienced as an expression of a grandeur and richness for we the living.

John Gillis is an architect in practice in New York and Kansas City. He is the author of Tidings of Joy and Comfort: Romanticism and Realism in Architecture, and Art in One Lesson.