Scientist of the Day - Heinrich Olbers

Heinrich Wilhelm Matthias Olbers, a German astronomer, was born Oct. 11, 1758. Olbers is known for two asteroids and a paradox. We begin with the asteroids. The first asteroid, Ceres, had been discovered by Giuseppe Piazzi on Jan. 1, 1801. Ceres was tracked for a short while, and then it disappeared behind the Sun. No one knew how to recover a lost solar system object whose orbit was only fractionally known, but young Carl Friedrich Gauss, eager to show off his mathematical skills, promptly came up with a method for working out an orbit from limited observations. Olbers, observing at his Bremen observatory, recovered Ceres on the last day of 1801, using Gauss’s method. Olbers continued to follow Ceres through the heavens, and three months later, on Mar. 28, 1802, he spotted another similar object. It came to be called Pallas, and because it was the second asteroid discovered, we now call it 2 Pallas, the number indicating the order of discovery (Ceres used to be called 1 Ceres, but since it was promoted to dwarf planet status in 2006, it is now just "Ceres"). In 1804, a third asteroid was discovered, by a different astronomer, Carl Ludwig Harding, and named Juno. And then, in 1807, Olbers discovered a fourth asteroid, which would be called Vesta, now 4 Vesta. For the next 38 years, those were the only four asteroids known. And Olbers discovered two of them.

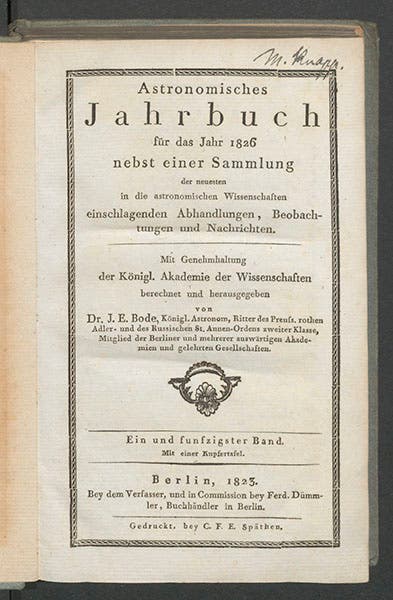

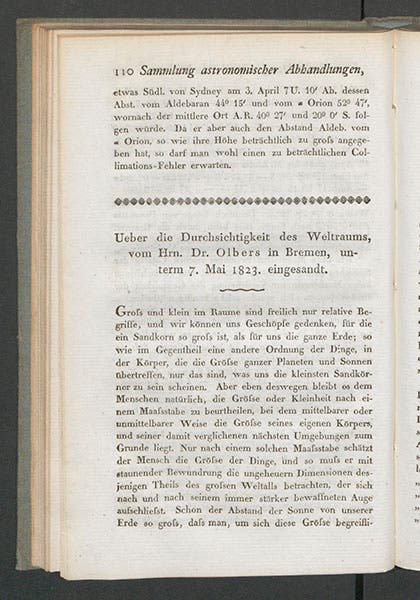

Olbers' other notable achievement was to point out a paradox – Olbers' paradox. In 1823, Olbers asked the simple question: Why is the sky dark at night? Olbers reasoned that, if there were an infinite number of stars in the sky, then no matter where we look in space, our line of sight should eventually terminate in a star, so the sky should everywhere be bright. The logic is sound, but the sky is not bright at night. Which is why we have a paradox. The paradox was pointed out and discussed by Olbers in an article called "Ueber die Durchsichtigkeit des Weltraums" ("Concerning the transparency of space"), in the German almanac published by Johann Bode, Astronomisches Jahrbuch für das Jahr 1826, printed in 1823 (citing almanacs is tricky, since they are usually published 3 years ahead of the year they are to be used. The practice is to cite the actual publication year, rather than the year in the title. So Olber’s paradox was announced in 1823, not 1826). We have the entire set of Bode’s Jahrbuchs in our collections; we show the title page of the 1823 volume, and the first page of Olber’s article (second and third images).

We now know that Olbers was not even close to being the first to pose the paradox that bears his name; he was preceded by Jean Philippe de Cheseaux in 1744, by Edmond Halley in 1718, and to some extent by Johannes Kepler in 1618, who used the paradox to argue that the universe must be finite. And during Olbers’ lifetime, it was never mentioned as one of his achievements, nor was it cited in any obituary after his death. But somewhere along the line, it became Olbers' paradox, and Olbers’ paradox it remains, precedents notwithstanding. The resolution of the paradox in the modern world is not straight-forward; but basically cosmologists explain the dark night sky by pointing to the fact that the universe we can see is only 14 billion years old, so that any line of sight that goes out more than 14 billion light years will not intercept a star, and also by reminding us that the universe is expanding, which makes light lose energy as it travels to us, so that once-bright light from the early universe would be stretched out to low-energy microwaves by the time it reaches us.

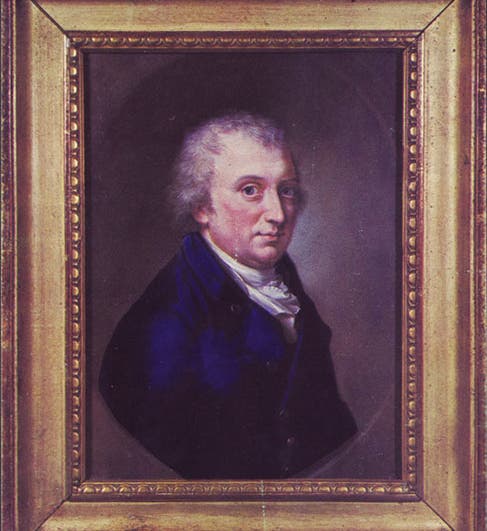

Olbers and Gauss became the best of friends, and in 1807, each commissioned a portrait of the other. The portrait of Olbers still hangs in the Göttingen observatory (first image). After Olbers death in 1840, a statue was erected in his honor in his home city of Bremen (fourth image). Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.