Scientist of the Day - James David Forbes

James David Forbes, a Scottish physicist, was born Apr. 20, 1809. Forbes was professor of natural philosophy at the University of Edinburgh and is noted for his extensive work on heat flow and infrared radiation. But he was also an authority on glaciers, and we are going to look at his contributions to glaciology today.

Forbes met Louis Agassiz in Glasgow in 1840, at a meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, where Agassiz announced his glacial theory and proposed the existence of past ice ages. He would publish his milestone book, Études sur les glaciers, that same year.

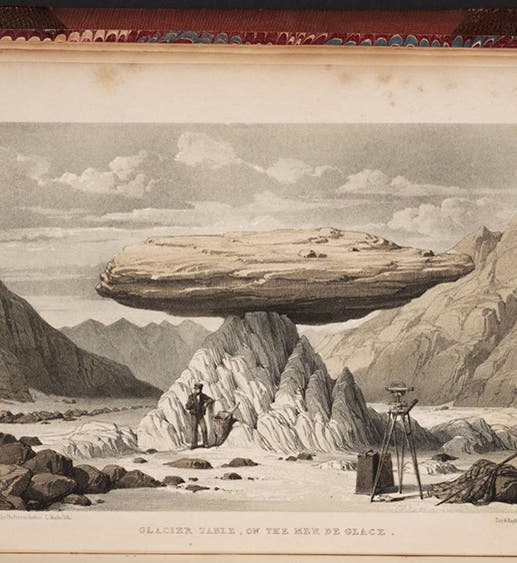

Forbes was intrigued and went to Switzerland to see for himself, and he came back convinced that glaciers had been a powerful force in earth history. In 1843, he published Travels through the Alps of Savoy and Other Parts of the Pennine Chain with Observations on the Phenomena of Glaciers, which was the first book in Great Britain to promote the glacial theory. It is illustrated with handsome lithographs, the most arresting of which is surely the frontispiece, which displays a glacial table on the Mer de Glâce (first image above). Glacial tables are formed when an erratic block screens the ice below it from the sun while the surrounding area melts away. That is supposedly Forbes himself standing beneath the boulder.

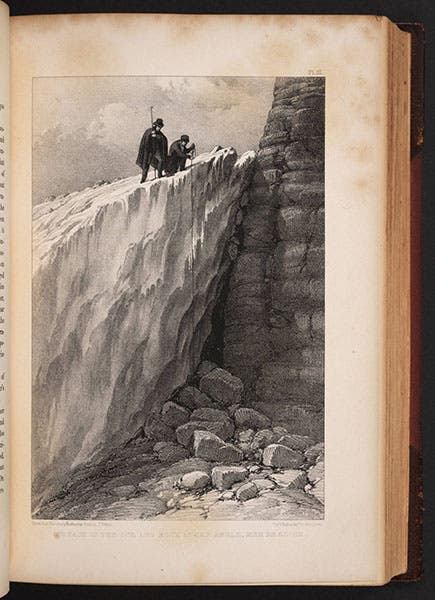

The Mer de Glâce is just what its name says, a sea of ice that flows down from Mont Blanc and the other peaks in its massif, located in the French Alps. While studying this glacier, Forbes and an assistant attempted to measure the thickness of the glacial ice. He did so with all the glaciers he visited, but this one is memorable because he commemorated it with an illustration in his book (fourth image, just above).

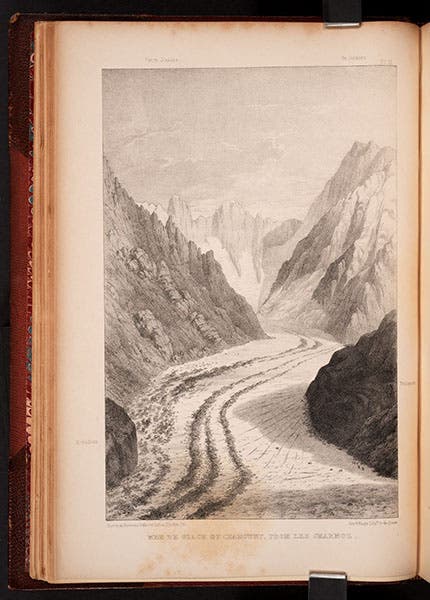

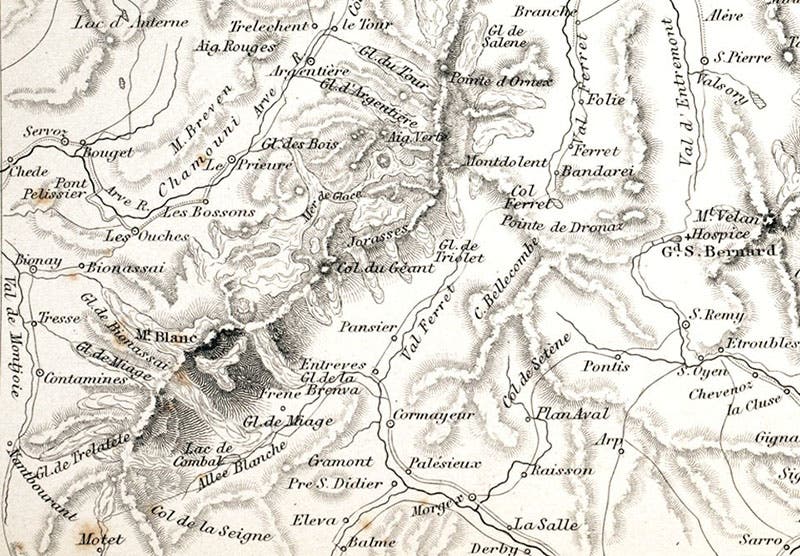

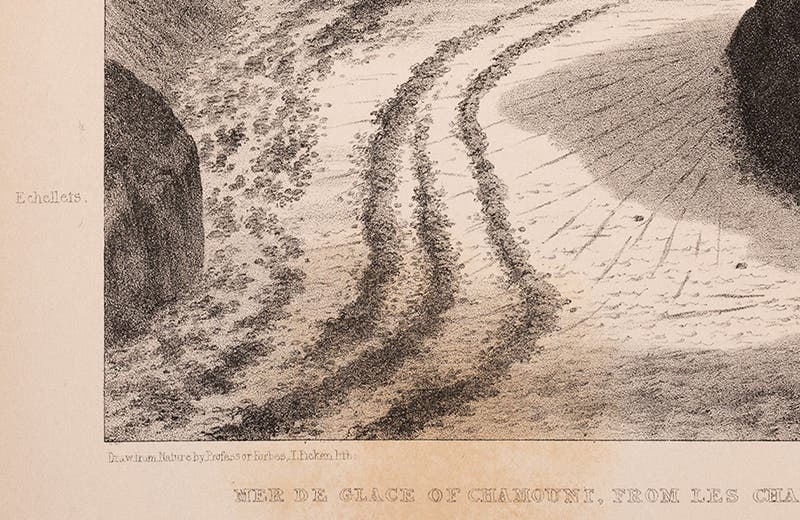

Forbes also included a drawing of wider scope of the Mer de Glâce, showing the glacier advancing down the Chamonix valley (fifth image, just above). The book contains a map as well, showing the entire glacial field of the Alps. We show here a detail centered on Mont Blanc and the Col de Geant (sixth image, just below). Just above Mont Blanc, the Mer de Glace is marked, and you can see the extent of the glacier. Note the Hospice du Grand St-Bernard at the far right.

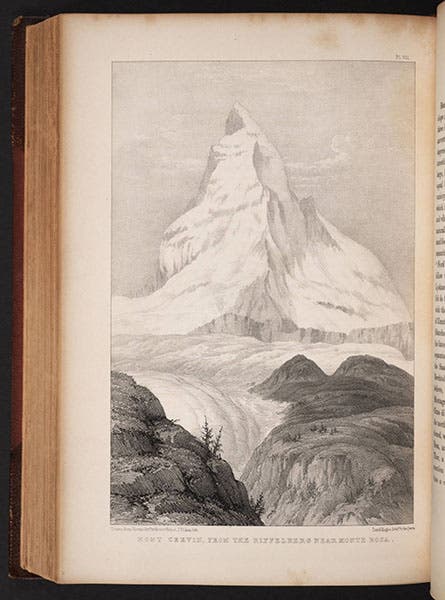

The other plate that we show from the book is the Matterhorn (third image). Forbes did his own sketches for all these plates; we show a detail of the Mer de Glace view, with Forbes’ name at the bottom as the artist (seventh image, just below). The lithographer here was Thomas Ashburton Picken, who worked for the firm of Day & Haghe and was trained by Louis Haghe. Picken did all the lithographs in the book except the dramatic frontispiece of the glacial table (first image). That was done by Louis Haghe himself, about whom we wrote a profile just last month.

The National Portrait Gallery on London has an interesting print with 14 portraits, etched in 1884 by William Brassey Hole. Each of the 14 was a deceased professor at Edinburgh University. James David Forbes is the darker figure in the third row from the top, looking off to the right. He is just below his namesake, Edward Forbes, who was once a Scientist of the Day himself. What appears to be the original pen and pencil sketch from which the etching was made, is in the National Libraries of Scotland. The drawing of Forbes there is slightly different, and, in my opinion, nicer.

We displayed Forbes’ book in our 2008 exhibition, Ice: A Victorian Romance where you can get a more detailed view of Forbes under the glacial table, and of his measurement of the thickness of glaciers.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.