Scientist of the Day - Johann Joachim Becher

Johann Joachim Becher, a German alchemist, was born May 6, 1635. Becher was one of the most renowned chemists of 17th-century Germany, but he is remembered today mostly as the instigator of the notorious phlogiston theory. In his Physica subterranea of 1669, he proposed the existence of three new chemical principles or “earths”. One of them, terra pinguis, was thought to be a substance present in inflammable materials and given off during combustion. In the early 18th century, terra pinguis was renamed phlogiston (Greek for combustible) and made the basis for a complete theory of combustion and oxidation. It was a very powerful theory, with a great deal of explanatory power, allowing chemists to understand nearly any chemical reaction in which heat was taken on or given off. The only trouble with the phlogiston theory is that it had everything backwards; combustion and oxidation do not involve the emission of phlogiston, but rather the incorporation of oxygen. It was such a different mindset that it was very difficult for Antoine Lavoisier to get fellow chemists to turn everything around in their heads and accept oxygen as the principle of combustion. Joseph Priestley, for example, when he discovered oxygen, insisted on calling it “dephlogisticated air”, since he thought it had the capacity to absorb large amounts of phlogiston, and thus encourage combustion. It is not really fair to Becher to lay all this in his lap—most of it wasn’t really his idea. But posterity has done so, and his legacy will just have to live with it.

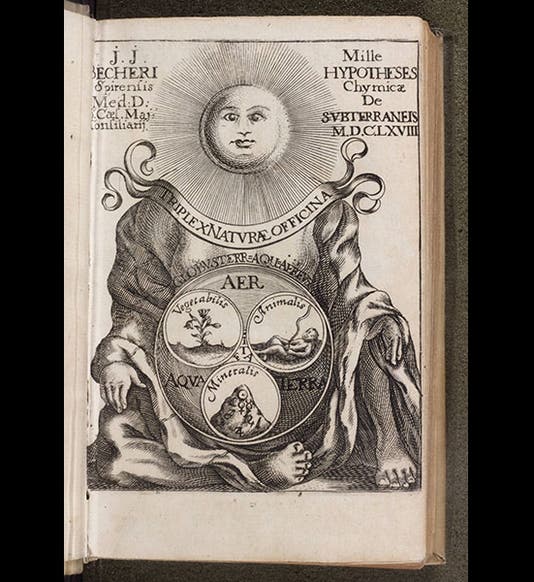

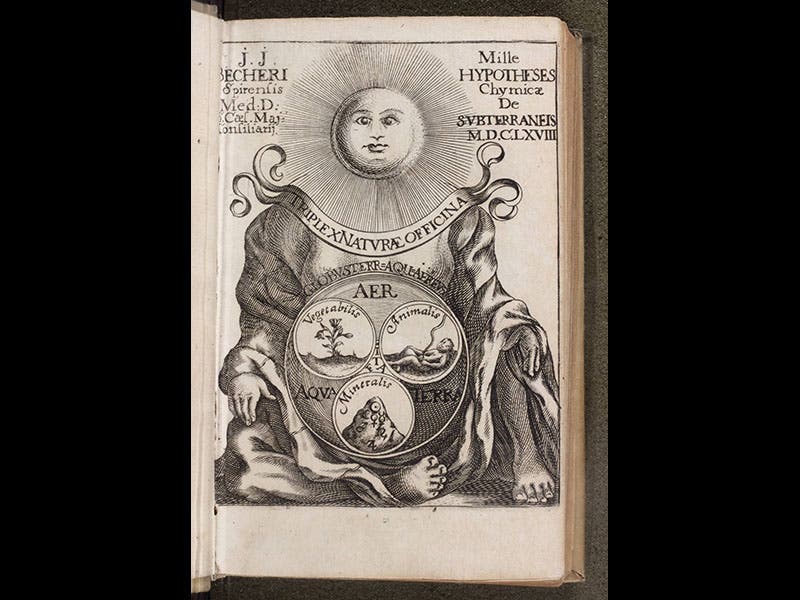

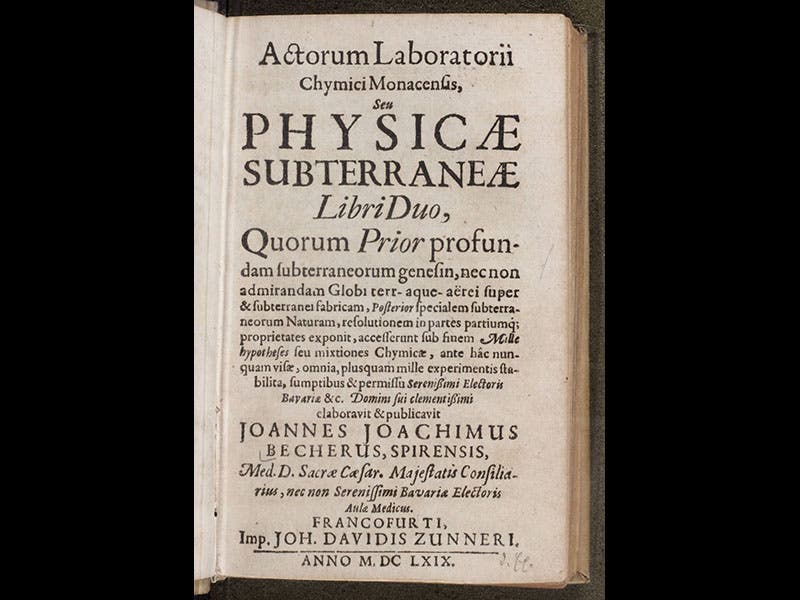

We have Becher’s Physica subterranea in the History of Science Collection (second image above), and a complete digital version in our Digital Collections. The book begins with a delightful frontispiece (first image), with one of the first allegorical representations of Mother Earth, cooking up subterranean metals and minerals in her womb. We displayed this engraving long ago in our Theories of the Earth exhibition, which is not available online.

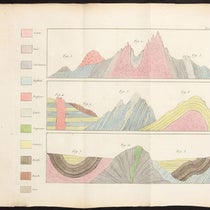

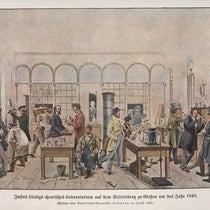

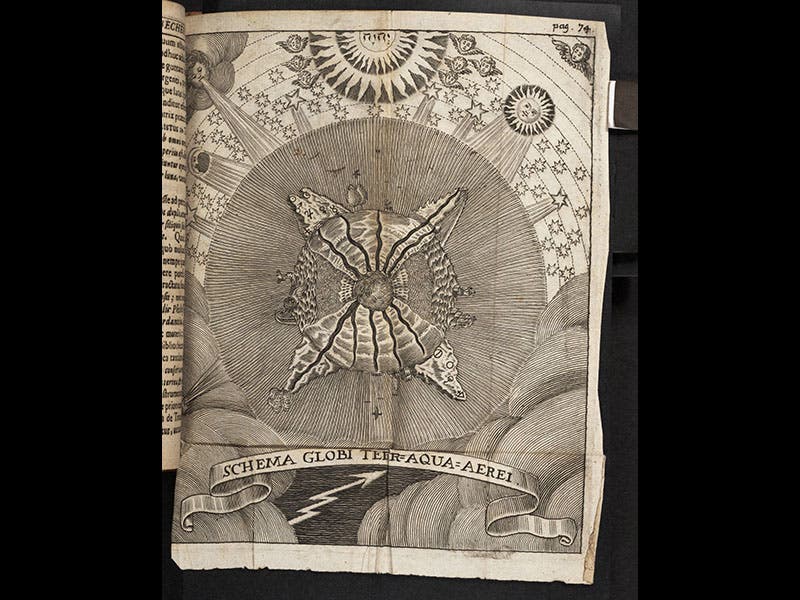

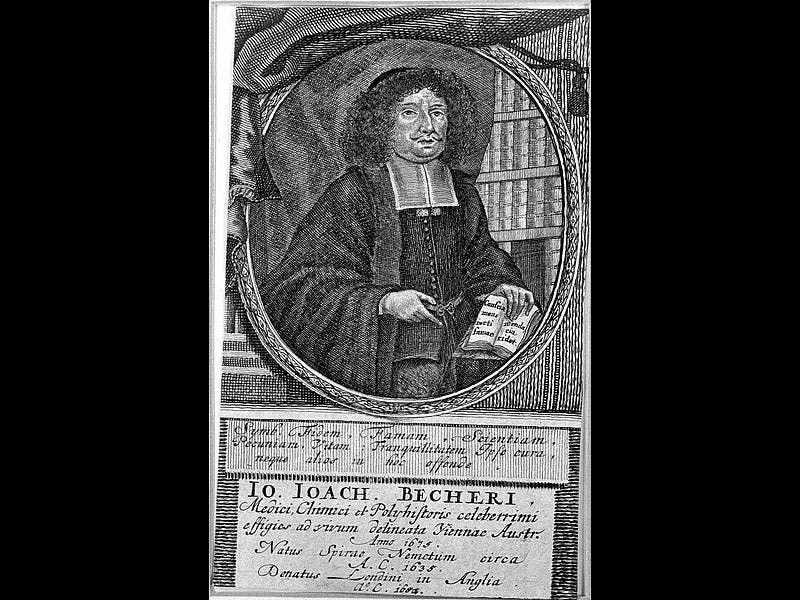

The other images show an earth cross-section, from his Opuscula chymica rariora (1719), also in our Collection (third image), as well as a portrait of Becher (fourth image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![“Aurora Borealis,” hand-colored wood engraving by Josiah Wood Whymper, [Natural Phenomena], plate 2, 1846 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/0245ffcb-b70c-477c-8792-0a73ebd54eb2/Whymper%2011.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)