Scientist of the Day - Johannes Fabricius

Johannes Fabricius, a Frisian/German astronomer, was born Jan. 8, 1587. Frisia was an ancient region with its own dialect, bordering the North Sea in what is now northeast Netherlands and northwest Germany; Johannes was from East Frisia, now part of Germany. His father, David, was also an astronomer (and a preacher in Osteel in East Frisia), and is himself known in astronomical circles for being the first to discover a periodic variable star (Mira Ceti) in 1596. We have written a post on David Fabricius and Mira Ceti.

In 1611, son Johannes came home from his university studies in Leiden with a new-fangled instrument, a telescope, which had been invented around 1608, and which Galileo Galilei had made famous in his Sidereus nuncius (Starry Messenger) of 1610. On Mar. 9 of 1611, Johannes, 24 years old, looked at the Sun with his telescope and noticed several dark blotches on the solar surface. He called in his father, and together they began to observe this new discovery: sunspots. They quickly learned to use a crude camera obscura (essentially a pin-hole camera) to project images of the sun onto a wall and spare their eyes from the glare. They then noticed that the spots moved across the face of the sun, and after disappearing over one edge, returned on the other after a few weeks, demonstrating that the sun rotates. Sometime that summer, Johannes published a small pamphlet on his discovery, De maculis in sole observatis, et apparente earum cum sole conversione narratio (Narration on Spots Observed on the Sun and their Apparent Rotation with the Sun), confirming Johannes' role as a discoverer of sunspots (first image).

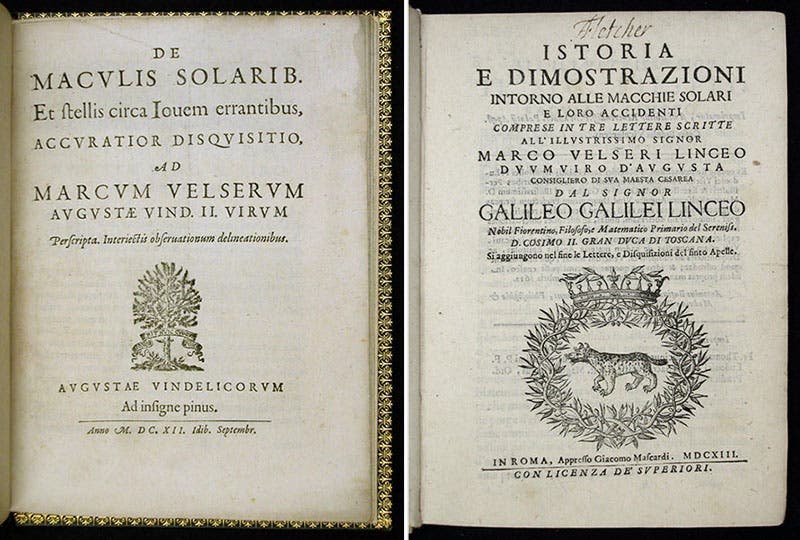

Title pages of treatises on sunspots by Christoph Scheiner (left), 1612, and Galileo Galilei, 1613 (right) (Linda Hall Library)

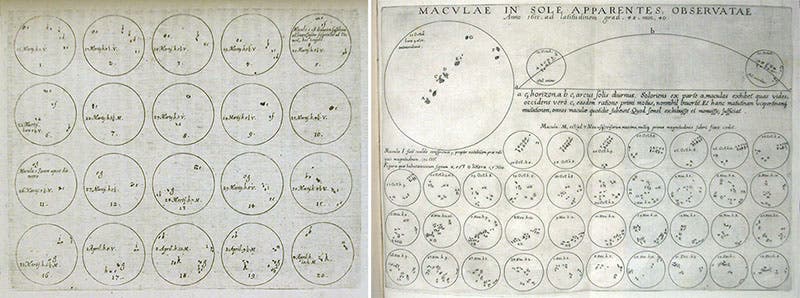

Unfortunately for Fabricius, his unillustrated pamphlet of 22 pages attracted little attention. Shortly thereafter, and independently of Fabricius, Christoph Scheiner and Galileo made the same series of discoveries. They each published treatises in 1612 and 1613 respectively and engaged in a protracted controversy over priority, and on the nature of sunspots. Poor Fabricius' treatise was never in the conversation; only Johannes Kepler seems to have noticed it (Kepler noticed everything), but Kepler participated little in the Galileo-Scheiner dispute. Even now, Fabricius is relatively unknown, even by historians of science. His treatise is quite scarce; there are only three copies in libraries in this country, and another currently on the market. We drew our images from the copy for sale, for we are not one of the three libraries with a copy of Fabricius’ book, although we have both Gaileo’s and Scheiner’s sunspot books (second – fifth images).

Illustrations of sunspots, engravings, from Christoph Scheiner, De maculis solarib., 1612 (left), and Galileo Galilei, Istoria e dimonstrazioni, 1613 (right) (Linda Hall Library)

Had Johannes lived a longer life, he might have been able to make his own case for being the true discover of sunspots. But alas, he died just five years later, at age 29, of unknown causes. His father lasted only one year longer, before he was clubbed to death by an angry peasant whom he accused of thievery from the pulpit. For a star-struck family, they shared an especially ill-starred fate.

There are not many other graphics we can offer, other than the pamphlet, and the images from Galileo and Scheiner. There are no portraits of David or Johannes; their graves are unknown; and their telescope does not survive in a Frisian museum. The best we can do is show you a modern photograph of the church in Osteel where the father preached (and was later struck down) and in the tower of which Johannes set up his telescope in 1611 and snatched his one claim to a fame that has been a long time coming.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.