Scientist of the Day - John Graham Dalyell

John Graham Dalyell, a Scottish lawyer, antiquary, and naturalist, died June 7, 1851; his day of birth in 1771 is not recorded. Dalyell is curious as a historical figure, in that he published widely on all manner of subjects, including three books on natural history, was highly respected by his contemporaries, became a baronet and was knighted by the crown, and yet he is almost completely unknown today. His books on invertebrate animals are insightful, original, beautifully illustrated, and hardly ever read.

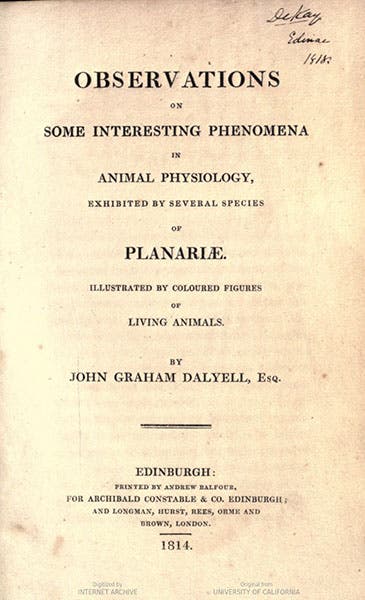

The one book of his that has received some acclaim, although in very exclusive circles, is Observations on some interesting phenomena in animal physiology, exhibited by several species of Planariae (1814). In it, Dalyell reveals an important discovery, that planariae – tiny worm-like animals – can regenerate all parts of their bodies. Cut off a head, and the head will grow a new body, and the body a new head. While regeneration as an invertebrtate phenomenon had been observed before, especially in hydra, by Abraham Trembley, no one had noticed regeneration in planaria before Dalyell. As a consequence, Dalyell is quite a hero to those engaged in planaria research today. It just so happens that one of the world’s foremost experts on planaria, Alejandro Sánchez Alvarado, runs a planaria lab at the Stowers Institute here in Kansas City, not a mile from our Library. On the lab's webpage, Dr. Sánchez Alvarado has constructed a timeline of planaria research, and he gives a prominent place to Dalyell.

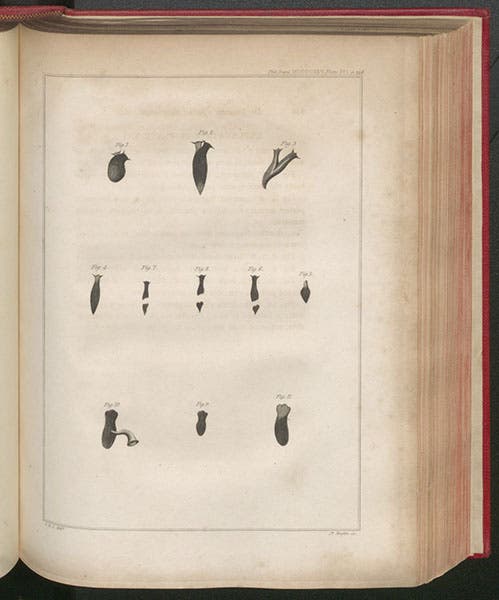

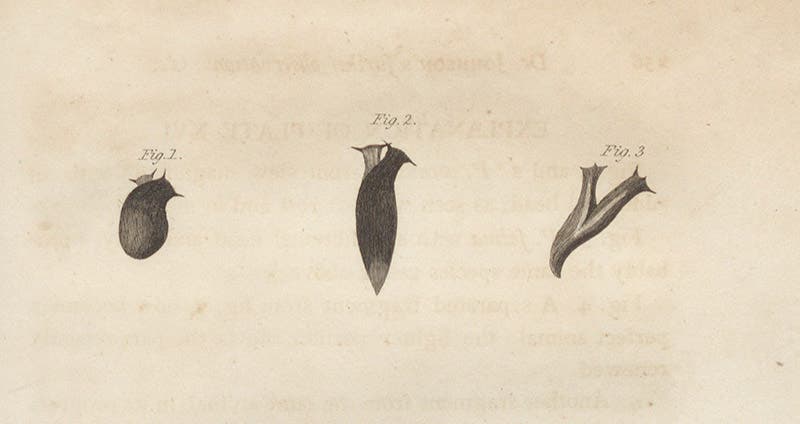

Dalyell's Observations was well enough known in its own day that Charles Darwin took a copy with him on the HMS Beagle. But when J.R. Johnson was doing his own planaria research in 1822, he published a paper in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, unaware of Dalyell's prior research. Someone informed him, and three years later he published a second paper (1825), in which he acknowledged that he had been anticipated in every way by Dalyell. But after that, Dalyell’s book seems to have disappeared. I am sure there are copies in Edinburgh and Glasgow, but in the United States, I have run down only two copies of the original pamphlet, at Cornell and the University of California. We do not have a copy in our Library and I have never seen one offered for sale. The only exemplar I have been able to consult is the digitized version of the University of California copy, available online. It was the source for our opening image, a detail of the one, hand-colored plate in Dalyell's 1814 book. The other images here (fourth and fifth images, below), which illustrate Dalyell's discoveries, come from Johnson's 1825 paper, which we do have.

Dalyell published two other works that have been even more neglected that his planaria pamphlet. Rare and Remarkable Animals of Scotland, with practical observations on their nature, a 2-volume work, appeared in 1847, containing 101 plates of all manner of marine invertebrates. I have never seen a copy. The Powers of the Creator displayed in the Creation; or, Observations on life amidst the various forms of the humbler tribes of animated nature, in 3 volumes, was published in 1851-58. Dalyell saw only the first volume, as he died in 1851. But colleagues saw it through the press, and volume 3 contains a memoir of Dalyell and a portrait. We have only the third volume in our Library, which is unfortunate, but at least we have his portrait (second image). The beginning of the title makes it sound like this book is just another venture into Natural Theology, like the Bridgewater treatises of the 1830s. But it is not. Dalyell’s observations on testacea and sponges, which I can read about in our third volume, are full of original details, describing the anatomy and behavior of various invertebrates; he even tells us where he obtained his specimens. And the plates – 37 in this third volume – are just gorgeous, full-page and hand-colored. The one I include here (sixth image, below) shows a Serpula contorta, a species of tube-worm, which Dalyell says are found in profusion on the rocks east of Portobello, in the Firth of Forth.

Dalyell died in Edinburgh and was buried in the graveyard of Abercorn Church, West Lothian (seventh image, below). As was to be expected, I could not find a photo of his grave. But I did find one of the tomb of his brother, William Cunningham Dalyell, who succeeded him as baronet and who died 14 years later. Presumably, John Graham is buried somewhere nearby.

I do not know why Dalyell has nearly disappeared from the historical record. I hope someone with access to all his publications will make an effort to bring him and his work back to life.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.