Scientist of the Day - John Lindley

John Lindley, an English horticulturist, was born Feb. 5, 1799. Son of a seed-merchant, Lindley was largely a self-taught botanist, working for Sir Joseph Banks as a young man, writing a few short monographs, joining the Linnean Society of London, and becoming a secretary to the Horticultural Society by 1822. He must have attracted favorable attention, for in 1829, he was appointed professor of botany at University College in London, which was only 3 years old at the time, and he held this position for 31 years.

Lindley was a tireless botanist, editing numerous journals and serving on the staff of several botanical gardens, writing encyclopedia entries, and publishing a number of books on general botany, fossil plants, and orchids. He also championed a "natural system" for plants, opposing the artificial sexual system of Linnaeus; Lindley’s natural system, although preferable to Linnaean taxonomy on principle, was not especially successful.

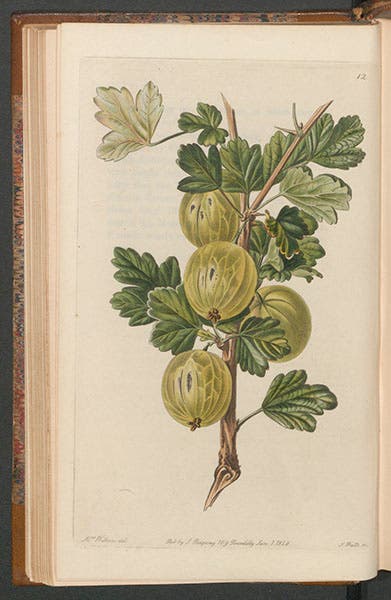

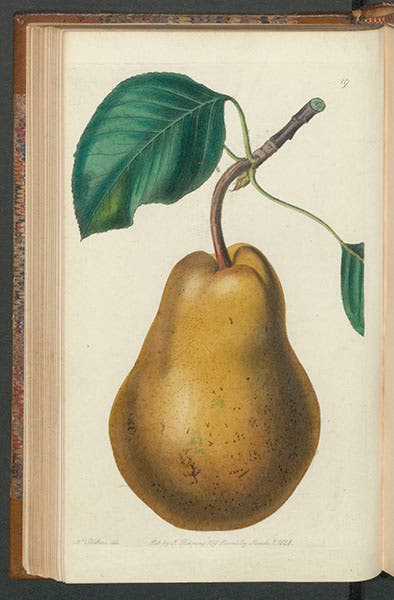

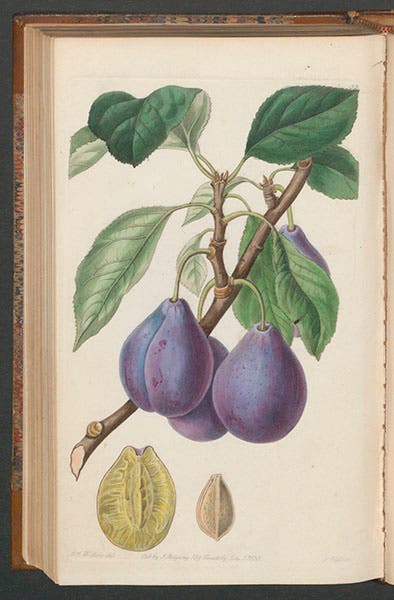

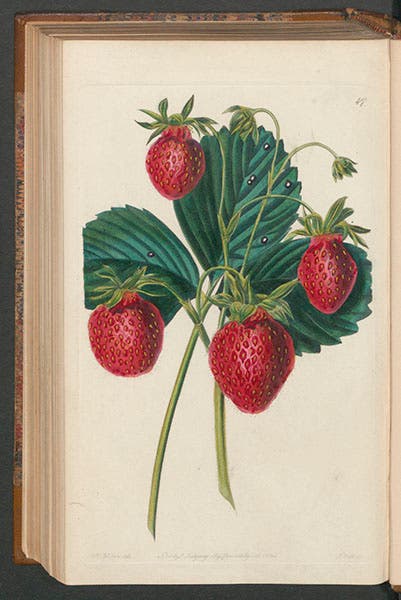

The work we are featuring today is Lindley’s Pomologia Britannica, an illustrated guide to edible fruit. It originally appeared as a serial, The Pomological Magazine (1828-30), and then was reissued as a 3-volume work in 1841, which is the version that we have in our collections. Except for the fact that it discusses plants, it is not especially botanical, since Lindley provided only common English names and made no reference to any taxonomic system at all. The text briefly covers flowers, leaves, and fruit, attention being given to edibility and/or success in prize competitions.

The real attraction of the book, as you have no doubt noted already, lies in the hand-colored illustrations. These were drawn mostly by a woman illustrator, Augusta Withers, and engraved by "W. Clark and S. Watts," who are otherwise unknown to me. Lindley deserves credit, one supposes, for hiring them, but little more for their accomplishment.

Making fruit attractive in print is not easy. The best way to convey the texture of fruit skin is with lithography. We featured another work on fruit, the Fruits of America by Charles Hovey in this space in the fall of 2018; that work used lithographs. In that post we provided a detail of one of the lithographs to show the effectiveness of stone for this purpose. Lindley’s work (the first version, The Pomological Magazine) appeared about 25 years before Hovey's, and while lithography was available then, it was only just establishing itself as a medium for botanical illustration. So Lindley (or rather Clark and Watts) used copper-plate engraving to reproduce Withers’ drawings. Line engraving tends to produce a hard, cold surface, but Lindley's engravers supplemented engraved lines with stipple, which, when augmented by hand-coloring, performs quite respectably in suggesting the skin of a firm but softening peach (fifth image).

The illustrations we selected to reproduce here (the process of which made us very hungry) are, in order: The Bellegarde peach (which also supplies the detail, (fifth image); Crompton's Sheba Queen gooseberry; the Beurre Diel pear; the Imperatrice plum; and the Old Pine or Carolina strawberry.

From 1847 to 1852, Thomas Herbert Maguire did a series of about 60 lithograph portraits of scientists for the Ipswich Museum. We have featured a few of these from time to time, as in our posts for Charles Darwin, Henry de la Beche, and Prideaux John Selby. Fortunately for today’s post, Maguire also executed a lithograph portrait of John Lindley; we show the print that is in the National Portrait Gallery (second image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.