Scientist of the Day - John Vanderbank

John Vanderbank, an English portrait painter, was born Sep. 9, 1694. Vanderbank was one of the most highly regarded portraitists in England in the 1720s and 1730s; his clients were mostly royalty and aristocrats – earls and duchesses, countesses and barons, and the occasional king. He became a pupil of Godfrey Kneller in 1711, and then studied for two years with James Thornhill, before setting up on his own in 1720. Since Godfrey Kneller painted two portraits of Isaac Newton, and Thornhill painted two as well, it should not surprise us that Vanderbank joined in with two Newton portraits of his own. Indeed, it is a good thing he did, or he would never have made it into our Scientist of the Day series.

Kneller first painted Newton in 1689, giving us a visual record of the author of the Principia (1687) in his prime. He painted another portrait in 1702, this time recording the soon-to-be president of the Royal Society and about-to-be-published author of his other major work, the Opticks (1704).

Thornhill painted his first portrait of Newton around 1710, and the second one shortly thereafter. These show the Newton of the controversy with Leibniz, and the Newton of the second edition of the Principia, revised and edited by Roger Cotes and published in 1713. In fact, an engraving of the second Thornhill portrait was given to Cotes by Newton himself, the only payment or even acknowledgement Cotes would receive for his considerable labors. Our former Rare Books Librarian, Bruce Bradley, published an excellent and well-illustrated paper in 2012 about "Newton's gift to Roger Cotes," disentangling the snarled mess of engraved portraits of Newton and determining which one Cotes actually received. You may read it here.

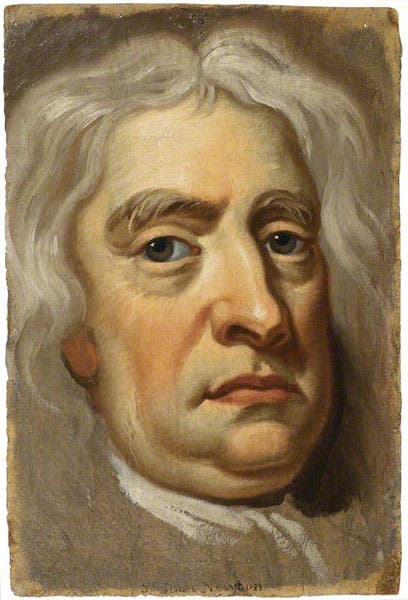

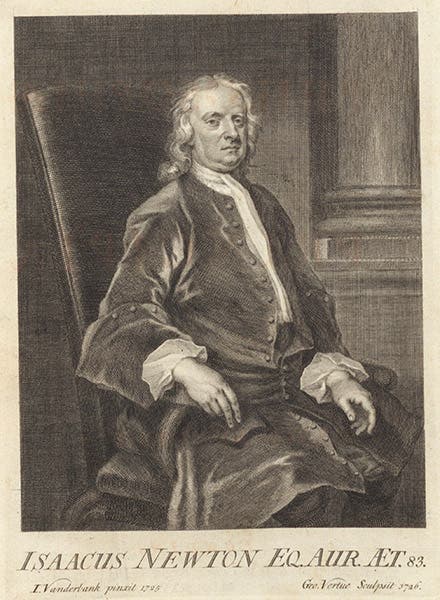

Vanderbank's portraits of Newton, painted in 1725-26, show the octogenarian natural philosopher. In actual number there are six of these, but three of them are copies, so in reality, Vanderbank painted two original oil portraits and an oil-on-paper preparatory sketch of Newton. The first portrait of 1725 is at Trinity College, Cambridge (first image); the oil portrait of 1726 (third image), and the preparatory sketch (fourth image), are at the Royal Society of London. At the time of the portraits, Newton was preparing the third and his last edition of the Principia. When that edition was published in 1726, it included as a frontispiece an engraving by George Vertue after the first Vanderbank portrait of 1725. It is the only edition of the Principia before Newton’s death (in 1727) to have a portrait frontispiece. We have all three editions of the Principia in our collections, which means we have that engraved portrait (fifth image, below). Both of Vanderbank’s portraits were also engraved by John Faber for sale to the public; these were mezzotints and proved to be quite popular.

The only other portraits of natural philosophers done by Vanderbank were two of Francis Bacon, made around 1731. These were both copies of 1618 portraits, so Vanderbank gets no credit here for originality, although he receives high marks for skill; we reproduce the more intimate portrait below (sixth image). These must have been painted on commission from a Bacon admirer, of whom there were many in Georgian England. Some art historian probably knows who commissioned them, but I do not. I do know that both are in the National Portrait Gallery in London. They do not know who commissioned them either.

Vanderbank might have painted more portraits of scientists, but he had a rather excessive life-style, always threatened by creditors because he spent most of his income on his mistress, and he was prone to “intemperance,” as George Vertue put it. Vertue was unhappy about this, because in his opinion, Vanderbank had more talent than any of his rivals in Georgian London. It would have been nice if Vanderbank had left us portraits of Hans Sloane or George Parker or James Bradley. Instead, he died of consumption in 1739, at the age of 45, his life as a painter only partially fulfilled.

Lady in a Blue Dress, oil on canvas, unknown artist, late 17th-early 18th century (Linda Hall Library)

Vanderbank executed quite a few portraits of fashionable women during his short career, including one that is usually referred to as "The Lady in a Blue Dress", which is in a private collection. This intrigues us, because our library has its own "Lady in a Blue Dress" oil portrait, hanging in the outer reading room of the History of Science Collection. Once optimistically believed to be a portrait of Nell Gwyn by Peter Lely, it is now unattributed, a portrait of an unknown lady; appraisers tell us it was possibly painted by Godfrey Kneller or someone from his workshop. Since Vanderbank came through Kneller’s workshop, perhaps he painted it himself. The Library has not made any of its works of art available to the public on its website, so I jumped into the breach with my iPhone and captured our own Lady in a Blue Dress (seventh image). May it one day prove to be our second Vanderbank work of art, this one an original.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.