Scientist of the Day - Jonathan Fisher

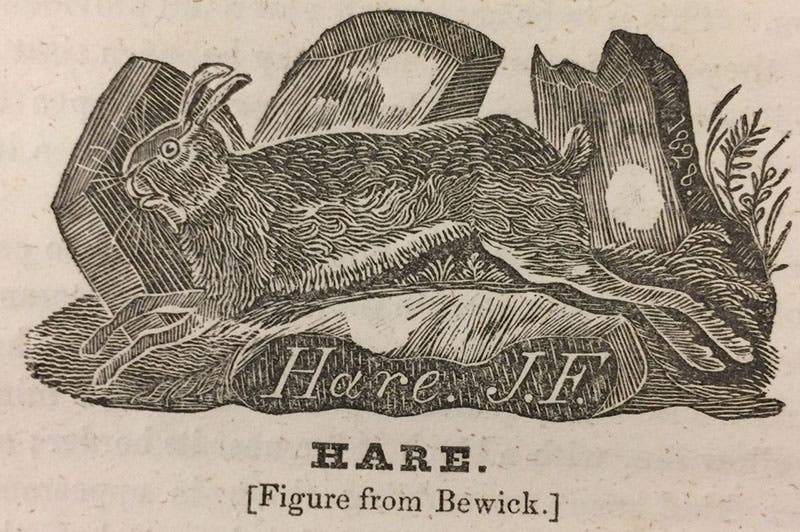

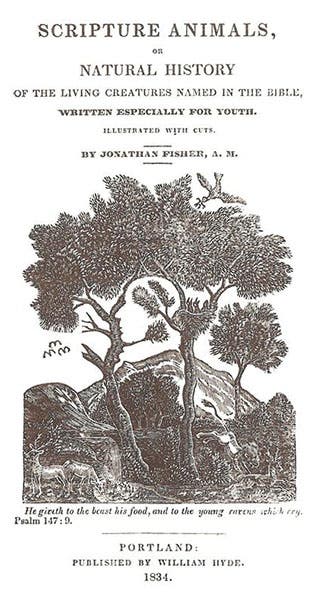

Jonathan Fisher, a writer, naturalist, artist, and Congregational minister, was born Oct. 7, 1768, in what were then the British colonies. Raised in Massachusetts and educated at Harvard, he moved north in 1796 to the hinterlands of Blue Hill, Maine, about half-way up the Maine coast on Penobscot Bay, to become a country parson, the first preacher in this budding little town. Since he got paid next to nothing for his ministry, he spent much of his spare time making ends meet by teaching drawing to students who boarded with him, farming his own acres, making straw hats and bone buttons for sale, painting signs for shopkeepers and sleighs for farmers, and making and repairing furniture for the entire town. He built his own house in 1797 and then a bigger one in in 1814, a house that still stands today. And what is the science connection in all this? In 1834, Fisher published a book, Scripture Animals, or Natural History of the Living Creatures Named in the Bible Written Especially for Youth, Illustrated with Cuts, which was printed in Portland, Maine. In the book, Fisher did exactly what the title advertised, discussing a variety of animals mentioned in the Bible and telling us precisely where in Scripture you could find their mention. But what makes the book memorable are the woodcuts, drawn and engraved (and signed) by Fisher himself. The original cuts are hard to locate on the web, with one notable exception – the Andover-Harvard Theological Library at Harvard Divinity School put up a post on Tumblr four years ago, reproducing 10 of Fisher’s wood engravings at a good resolution, from which we have borrowed our two images here. Fisher was obviously influenced by the wood engravings of Thomas Bewick, but he clearly developed his own style. His prints are as charming as any 19th-century animal images you are likely to find, and some of them remind me, I must say, of the work of the renowned 20th-century book illustrator (and woodcut artist) Barry Moser.

I must confess another reason for my fondness for Reverend Fisher: he helped found the lovely town of Blue Hill, where I spent many summers of my formative youth and from which the maternal side of my family descends. I have been to the Jonathan Fisher House in Blue Hill (which has a nice webpage about their namesake and his artwork), and I have walked many of the paths and streets he walked, and perhaps saw descendants of the animals that he drew for his book (Fisher copied many of his woodcuts from other prints, but some he drew from life, like the bear). I have not been to the Farnsworth Museum in Portland, which has a painting of Blue Hill by Fisher, signed and dated 1824, and which in 2013 mounted an exhibition in honor of Fisher and his Scripture Animals (there are no details, alas, on the webpage). We do not have a copy of Fisher's Scripture Animals in our History of Science Collection, and even though the book is perhaps more religious tract than natural history, I often think we ought to acquire it just for the wood engravings, which present such a contrast to the engavings by Bewick that everyone else of Fisher’s age was copying.

Or perhaps we should just buy Fisher’s book for the title page (third image). Look carefully at the title-page vignette, and you will see that even when it came to printing his own portrait, Fisher did things differently. Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.