Scientist of the Day - Joseph Glanvill

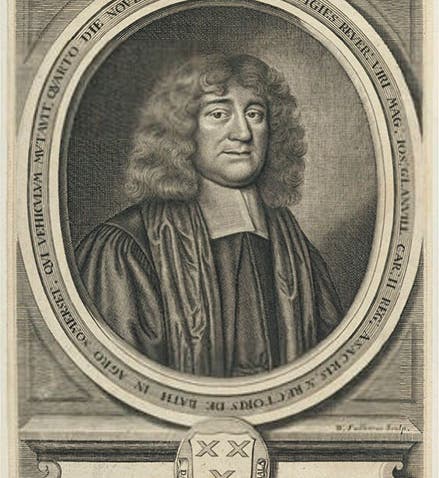

Joseph Glanvill, a clergyman and polemicist for the "new science," died Nov. 4, 1680, at the age of about 44; his date of birth is not recorded. The Royal Society of London was founded in 1660 and chartered in 1662, and its program was to promote the "experimental philosophy." Indeed, part of each meeting was devoted to a new experiment, conducted by its Curator of Experiments, Robert Hooke. Since this way of learning was quite different from that practiced at the universities of Oxford and Cambridge, where Scholasticism and adherence to Aristotle still held sway, it is not surprising that the activities of the Fellows of the Royal Society should have come under criticism and indeed ridicule from academics. In response to such criticism, several apologists for experimental science came forth in the 1660s. The most famous is Thomas Sprat, whose History of the Royal Society, published in 1667, ably defended the activities of the Royal Society and came with, at least in some copies, a frontispiece that paid homage both to Francis Bacon, the considered father of the new scientific method, and the experimental apparatus with which the new science was pursued. We have not yet written a post on Sprat, but we own his book, and you can see the famous frontispiece here.

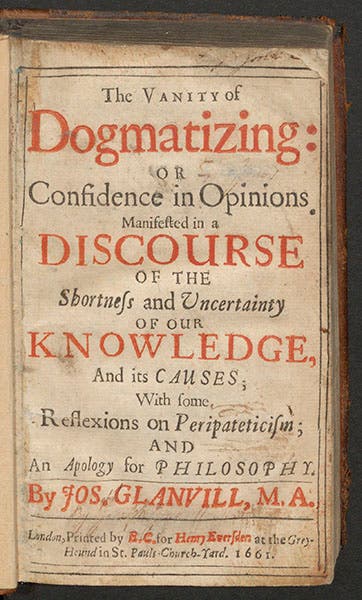

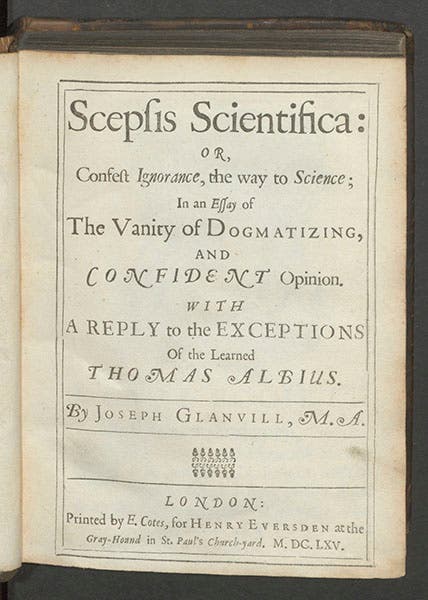

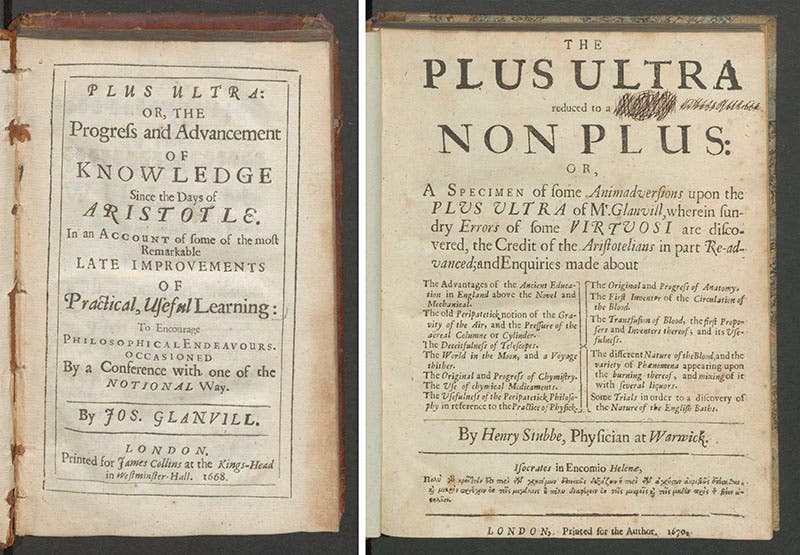

But if Sprat is the more famous apologist, Glanvill was perhaps the better one – certainly he was more prolific. The Royal Society was only one year old when Glanvill published The Vanity of Dogmatizing (1661), and he published three more before his early death: Scepsis scientifica (1665; third image), Plus Ultra (1668; fourth image), and a response to a critic, Henry Stubbe, whose delightfully titled Plus Ultra Reduced to a Non Plus (1670; fifth image) prompted Glanvill's A Praefatory Answer to Mr. Henry Stubbe in 1671. We have all of these and several more Glanvill books in our History of Science collection, and we show several of the title pages with our post.

Title page of Joseph Glanvill, Scepsis scientifica, 1665 (Linda Hall Library)

Glanvill argued that experimental philosophy was preferable to academic scholasticism because, in the past half-century, it had yielded more understanding of Nature than two thousand years of following Aristotle. Indeed, the title of his Plus Ultra continued: or, The progress and advancement of knowledge since the days of Aristotle. In an account of some of the most remarkable late improvements of practical, useful learning: to encourage philosophical endeavours. Glanvill cited the work of William Harvey, who discovered the circulation of the blood, which had eluded all the followers of ancient anatomy and physiology. He praised the new knowledge of our solar system revealed by Galileo and Johannes Kepler. Robert Boyle's work with the air pump, and Hooke's pursuits with the microscope were singled out for special admiration. The best thing about the new science was that it promised to be "useful", which had never been a concern of Aristotelian natural philosophy.

Title pages of Joseph Glanvill’s Plus Ultra, 1668, which was attacked by Henry Stubbe in The Plus Ultra Reduced to Non Plus, 1670 (Linda Hall Library)

In his emphasis on “useful philosophie”, Glanvill was following the lead of Francis Bacon, whose utopian New Atlantis was built on the premise that experimental science would lead to social improvement. Indeed, the title of Glanvill's third book, Plus Ultra, was an homage to Bacon, who are argued strenuously that, like the intrepid explorers of the material globe, who had sailed through the Pillars of Hercules to discover new lands, the investigators of the "intellectual globe," the world of the mind, must also “go further”, if knowledge is to be increased. When we featured Francis Bacon in this space last year, we included three Baconian engraved title pages in which the central theme was this very idea of Plus ultra – of daring to open up the Intellectual Globe.

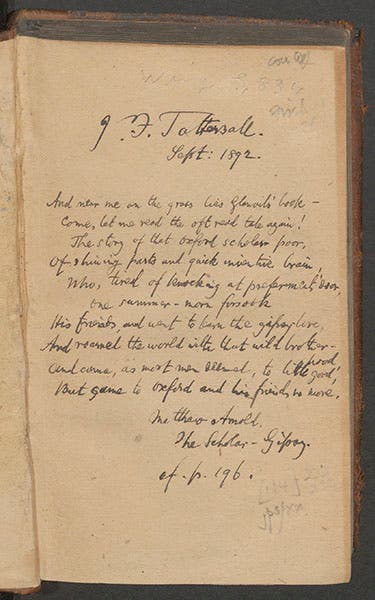

Front free endpaper of the Library’s copy of Joseph Glanvill, The Vanity of Dogmatizing, 1661, with a passage copied out by a former owner from Matthew Arnold, “The Scholar-Gipsy” (Linda Hall Library)

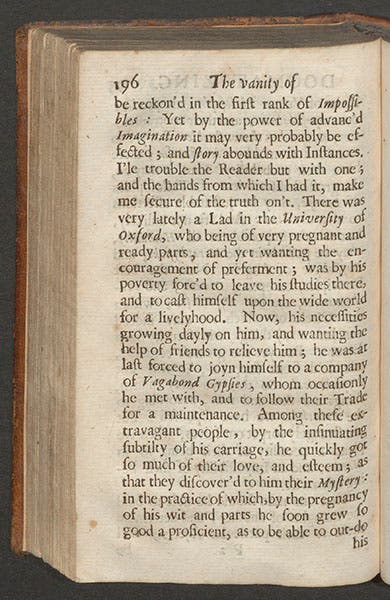

Our copy of Glanvill’s The Vanity of Dogmatizing is interesting for another reason. A Victorian owner in 1892 copied out a section of verse from Mathew Arnold's poem “The Scholar-Gipsy” onto the front free end-paper (sixth image). He did so because Arnold's poem was inspired by a passage in Glanvill's book, where Glanvill tells the story of an Oxford student who got so tired of Oxford ways that he took up with a troupe of “Vagabond Gypsies” and learned to look at the world in a new way. Arnold actually mentions Glanvill by name several times in the poem, including the passage written out in ink by the book’s former owner. Just because we can, we show you the paragraph, p. 196, where Glanvill introduces his Scholar-Gypsy (seventh image). If you would like to read more of Arnold’s “The Scholar-Gipsy” (1853), here is a useful online version.

Page 196 of Joseph Glanvill, The Vanity of Dogmatizing, 1661, with the story of the Oxford scholar turned Gypsy (Linda Hall Library)

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.